Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

News + Events

"Essential Documentation." Adaptive Reuse in Latin America: Cultural Identity, Values and Memory

Adaptive reuse in Latin America in 2023 is a practice that focuses on preserving cultural identity, values, and memory through the renovation and repurposing of historical buildings and structures. This approach aims to maintain a strong connection to the region's rich cultural heritage and traditions while promoting sustainability and economic development. It involves converting old, often neglected buildings into new, functional spaces, such as museums, community centers, or housing, which celebrate and preserve the history and identity of the area. Adaptive reuse is a means of breathing new life into architectural gems, keeping them relevant for future generations, and maintaining a sense of cultural continuity in the rapidly changing urban landscapes of Latin America.

Reflective socio-ecological practice

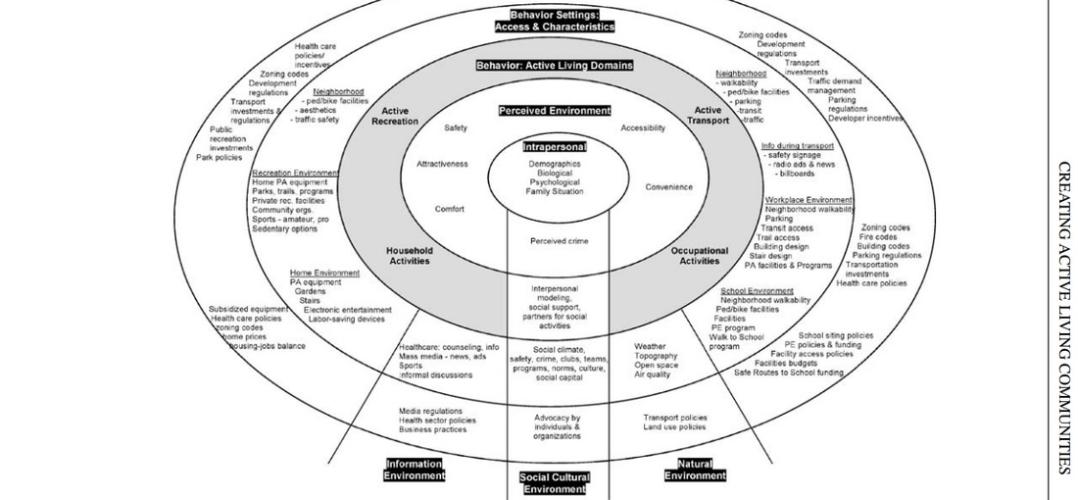

This autobiographical reflection traces my work in land suitability analysis and plan-making. The suitability practice has resulted in two rating systems: the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Land Evaluation and Site Assessment System and Green Business Certification Inc.’s SITES Rating System. Plans have been made for US counties, cities, and towns; Italian provinces; regions and watersheds; and university campuses. My practice is grounded in human ecology. I have attempted to address the issues people face with an especial focus on environmental quality and social equity. Examples of work from Ohio, Pennsylvania, Washington, Idaho, Colorado, Arizona, and Texas in the United States as well as Italy and Mexico are noted. I explore how reflection, often with collaborators and students, has informed my practice and how it can help advance the fields of planning and landscape architecture.

MEGA-ECO: A Symposium on Very Large-Scale Landscape Projects

For nearly a century, a new breed of landscape infrastructure megaproject has gone unrecognized, and is now proliferating, according to the organizers of a public symposium at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design set for October 5, 2023. These projects are designed to address biodiversity loss, land degradation, and climate change while improving living conditions for the Earth’s eight billion human inhabitants. Representing trillions of dollars in potential investments, can they deliver the ecological transformation they promise?

MEGA-ECO: A Symposium on Very Large-Scale Landscape Projects brings together designers and land managers for ecological restoration megaprojects in China, Pakistan, Brazil, Africa, Korea, Saudi Arabia, Canada, and the US to explore cross-border approaches to connectivity, anti-desertification, watersheds, and metropolitan development. They include representatives of the World Wildlife Fund, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, and the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, among others, who will discuss the Four Major Rivers Restoration Project (China); Forest Conservation in the Heart of the Colombian Amazon; Great Green Wall Initiative (Africa); São Paulo Greenbelt and Biosphere Reserve (Brazil); Sponge Cities Initiative (China); Upper Mississippi River Restoration Program (US); Upscaling Green Pakistan; and Yellowstone to Yukon (North America).

The program opens with a keynote talk by author Tony Hiss, co-creator of the half-earth movement (50x50) and visiting scholar at the Wagner School of Public Service, New York University.

The symposium is organized into four sessions, with presentations from each project representative followed by a discussion with expert panelists:

- Keith Bowers, Landscape Architect and Founder, Biohabitats

- Dr. Gary Tabor, Founder and Director, Center for Large Landscape Conservation

- Dr. Emmanuelle Cohen-Shachem, Nature-based Solutions, Thematic Lead, International Union for Conservation of Nature

- David Kuhn, Lead, Corporate Resilience, World Wildlife Fund

- Tyra Northwest, Traditional Land Use Lead, Samson Cree Nation, and co-founder, International Buffalo Relations Institute

Panel 1: Connectivity

- Dr. Jodi Hilty, Chief Scientist and President, Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y)

- Dominique Bikaba, Founding Member and Executive Director, Strong Roots Gorilla Corridor

- Ana Maria Gonzalez Velosa, Amazon Sustainable Landscapes Program Coordinator: Team leader, World Bank

- Andrea Fernanda Calderón, Technical Liaison of the Natural Heritage Project, North East Amazon Environmental and Sustainable Development Corporation (CDA), Proyecto Corazón de la Amazonia

Panel 2: Anti-Desertification

- Dr. Elvis Paul Nfor Tangem, Coordinator of the Great Green Wall Initiative

- Faiz Ali Khan, National Director, Upscaling Green Pakistan (formerly the Ten Billion Tree Tsunami Programme)

Panel 3: Watersheds

- Ben Valks, Creator/Visionary of the Araguaia Biodiversity Corridor

- Marshall Plumley, Regional Program Manager, Upper Mississippi River Restoration Program

- Yongjun Jo, Landscape Architect

Panel 4: Metropolitan Projects

- Hexing Chang, Associate Principal, Turenscape

- Rodrigo Victor, Professor, University of São Paulo

Concluding remarks will be delivered by Matthijs Bouw, Associate Professor of Practice at the Weitzman School of Design.

MEGA-ECO is presented by The Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology and Penn Global, and is organized by Rob Levinthal, PhD candidate in the Department of City & Regional Planning, and Richard Weller, professor of landscape architecture.

MEGA-ECO builds on the 2019 publication Design With Nature Now, a re-assessment of the legacy of Ian McHarg’s landmark 1969 book Design With Nature which was co-edited by Weller along with Penn faculty members Frederick Steiner, dean and Paley Professor; Karen M’Closkey, associate professor of landscape architecture; and Billy Fleming, Wilks Family Director at The McHarg Center.

The public symposium on October 5 is followed by an invite-only roundtable on October 6. Admission to the symposium is free and open to the public with advance registration.

Link to register: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/mega-eco-project-symposium-tickets-7087385…

Field Notes Towards an Internationalist Green New Deal

The McHarg Center's Climate Policy Research Group has published Field Notes Towards an International Green New Deal. This three year digital project was produced by RAs Palak Agarwal, Selina Cheah, Yixin (April) Wei, Ian Dillon, Zane Griffin Talley Cooper, A.L. McCullough, and the Wilks Family Director, Billy Fleming. Field Notes ask what it might mean for the rest of the world if the US realizes an eco modernist vision for the energy transition.