Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

News + Events

Design with Nature Now, with Dr. Frederick Steiner

Co-executive director Fritz Steiner talks about the legacy of his mentor (and the name sake of The McHarg Center) Ian McHarg, whose visionary approach to regional planning included coastal resilience.

Modeling and Monitoring Landscape Change

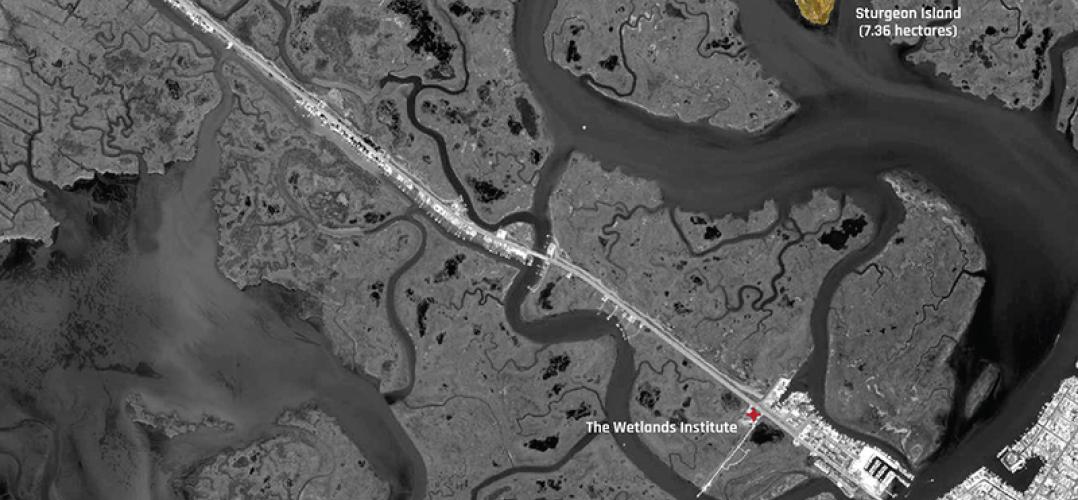

Before landscape architects can make decisions about how best to intervene in a landscape, they need data about the land itself: What its components are, how it moves, how it’s likely to change. Often, though, that data is collected by professionals in other disciplines, or government authorities with agendas of their own. Rather than taking that information for granted, says Keith VanDerSys, senior lecturer in landscape architecture, landscape architects can use emerging technologies to generate data of their own.

Q&A: Robert Gerard Pietrusko, Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture

This semester, Robert Gerard Pietrusko joined the standing faculty of the Department of Landscape Architecture as an associate professor, following a decade on the landscape architecture faculty at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. His design work, which is produced under the name of his studio, WARNING OFFICE, has been exhibited in more than 15 countries, and he a fellow at the American Academy in Rome in 2021. An inveterate polymath, Pietrusko earned a Bachelor of Music in Music Synthesis from the Berklee College of Music, a Master of Science in Electrical Engineering from Villanova University, and a Master of Architecture from the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University.

Crises and Contestations: The Promise and Peril of Designing a Green New Deal

It is clear that we are facing a tipping point in global politics, climate change and social justice. Much has been trumpeted under the banner of the ‘Green New Deal’. Billy Fleming, the Wilks Family Director of the Ian L McHarg Center at the Weitzman School of Design, University of Pennsylvania, describes the history and various approaches encompassed within this ubiquitous epithet and how designers can get involved.