Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

New Ruralism

Our field is obsessed with the urban experience. In a recent Zoom lecture with top professionals in our field, I listened to designers speak about Place and what type of landscapes inspire them. As numerous designers I admire spoke about Rittenhouse Square and Central Park, I couldn’t help feeling disillusioned by our narrow vision of landscape architecture. Besides memories of early family road trips to Yosemite or hiking the Appalachian Trail, Place for most of them was defined by its urban qualities and its ability to provoke spontaneous interactions with strangers, keep eyes on the streets, and bring diverse groups of people together through a shared interest in their environment.

As they spoke, I began to imagine these descriptors in the unincorporated town where I grew up. Thinking of an area where people might “bump” into one another was challenging. I settled on the strip mall that includes the grocery store, hardware shop, and veterinary clinic. It shares an intersection with the town bar, a newly established pie shop, and a Shell gas station and seems like the most likely spot for a “town center.” However, early in my vision quest, America’s car-centric landscape became an issue. My mind couldn’t force people out of their cars, and if it could, it was only for the 10-yard walk to the store they had parked directly in front of. While I could envision a couple of people mingling at the pie shop or the Drinkin’ Dog (the bar once aptly named for the large number of dogs on barstools), it was increasingly difficult to muster up any inspiration comparable to the magical experiences I fell in love with while living near the Italian Market in Philly or along a bike route in Portland, OR.

This was only a silly thought experiment, but it speaks to a larger issue across our nation and at the heart of our profession: the rural/urban divide. Every 2 years, we face an onslaught of red and blue maps that force us to reckon with the vast divisions between rural and urban communities. While much of the divide falls on strictly socioeconomic and political ground, we, as landscape architects, must be aware of our role both in creating this divide and in developing potential ways to bridge the divide. As designers, we have largely ignored our rural landscapes and focused on the urgencies of our cityscapes, for example, food access, rising sea levels, heat island effect, placemaking, and preservation. Our firms are based in urban areas, our most famous work depends on urban density, and we have a fascination with urban plazas, urban ecology, and urban streetscapes. When we do focus on rural areas, it is most often out of consideration for future urbanization.

Landscape Architecture’s rural neglect may come as a surprise for anyone familiar with the renowned methodologies of Ian McHarg. McHarg studied a number of rural areas in depth, and his focus on ecological patterns and processes as guiding forces for landscape interventions depended largely on rural areas.[1] However, McHarg’s work has also drawn designers away from the rural context and towards the city for a number of reasons. First, because McHarg’s methods serve as a “device for protecting natural process,” many designers find interventions into a rural landscape to be “arbitrary, capricious and inconsequential.” In other words, because of their “untapped” wilderness, biodiversity, historical geology and more, rural landscapes are deemed too precious to intervene in. Second, McHarg’s prospective land use frameworks have enabled designers to plan for or prevent urbanization, as opposed to homing in on ruralism itself. Finally, McHarg’s methods are well adopted by urbanists, and his “layer cake” analysis applies seamlessly to the natural and cultural features of the urban landscape.[2] Even McHarg advocated for shifting his philosophies beyond the rural and into the urban sphere: “The method can enter the city and we can proceed with our now familiar body of information to examine the city in an ecological way.”[3]

We must come to terms with our urban bias and begin to ask ourselves: what is rural landscape architecture and what are its methodologies? What does a rural landscape architecture framework look like and how do we begin to mold, grow and employ one?

Today, our society at large often sees ruralism as a stage prior to urbanism, or as an obsolete or derelict piece of the past. However, rural areas play a vital role in our future and our notions of progress. As designers concerned with sustaining and regenerating the diversity of our cultural and ecological landscapes, we must come to terms with our urban bias and begin to ask ourselves: what is rural landscape architecture and what are its methodologies? What does a rural landscape architecture framework look like and how do we begin to mold, grow and employ one?

Rural Past:

Our definitions of rural have almost always been residual. The US Census first started releasing urban population data in 1874.[4] In 1910, the US Census officially defined urban areas as, “incorporated places with populations of 2,500 or more.”[5] This definition resulted in a subsequent, unofficial definition for what urbanism left behind - the rural. Rural is now defined as “any place with populations of 2,500 or less,” or “a territory, population, and housing units not classified as urban.”[6] While the official definition of urban will continue to change to incorporate sprawl, suburbs and urban clusters, the rural continues to stay constant.

Although our understanding of the rural has grown beyond the census’ definitions, we often revert back to the association of the rural to the past. This is partially because early definitions of rural were functional, meaning they defined rural by its agricultural dominance, small settlements, and “cohesive identity based on respect for the environmental and behavioural qualities of living as part of an extensive landscape,” as Paul Cloke explains in his essay “Conceptualizing Rurality.”[7] Creed and Ching, leading sociologists on rural identity, describe how these definitions of a functional centrality such as agriculture, are “often sentimentally associated with a sublimely unpeopled wilderness or a severe agrarian past.”[8] The relegation of rurality to its agrarian past is quite problematic, as it propagates the rural/urban divide and washes over the complexity of rural identities.[9]

This notion of a rural past is true not only in America. In Japan, the term furusato, which directly translates to “old village,” or “native place,” is used by the Japanese tourism industry, politicians, city planners, and the general public to evoke a collective nostalgia for a quickly vanishing rural past.[10] The concept of “rural nostalgia” has become “the dominant imagination of post-postwar Japan.”[11] Furusato is a great example of how rural has grown beyond commonly understood notions of place. As rural sociologists have noted, rural society and rural space have become separate entities, thus untying rurality’s previously defined dependence on a specific geographic condition.[12]

Rural Reality

We have reached a point where the division between the rural past and urban future is so strong that we cannot separate progressive ideals from the urban or reassociate such topics with the rural. For example, progressive notions around climate change, racial equity, access to the outdoors, immigration reform, and local production are all thought of as largely urban issues despite their obvious relevance to all spatial configurations. We link all of these issues with urbanites because the majority of supporters and demonstrations reside in urban areas. Meanwhile, we continue to push rural into the past, widening the divide. If instead, we begin to turn this definition over, we see it isn’t such a stretch to start to envision these ideas of progress residing in and even sprouting from the rural. Rural areas not only house and produce our most important natural resources, including: food, water, minerals, and energy, but they also host future innovations in renewable energy and land management practices and embody diverse cultures and histories. Recent events have made it even more critical that we turn our attention to rural areas. Thousands of people are leaving crowded cities due to Covid-19 while rural hospitals are overburdened with rising cases, hurricanes have flattened crop fields, and wildfires in the west have burnt rural towns to the ground.

Most conversations surrounding rural America continue to be white-washed, despite the history of non-white rural populations, the current presence of rural populations of color, and the national dependency on in rural migrant workers. In our white-washed version of rural America, we ignore the history of enslaved, imprisoned and excluded African Americans, Native Americans, Japanese Americans, Mexican Americans and other ethnic minority groups. Despite the stereotypes of white “hillbillies,“ “rednecks,” and other derogatory terms so often associated with American ruralism, our rural communities are increasingly diverse. Today, over half of all Native Americans live in rural areas.[13] A large number of refugees are being resettled in small towns across Texas, Washington and Ohio and throughout the United States.[14] A 2016 study of 2,767 rural communities found that on average, the adult native-born population declined by 12% while the adult immigrant population grew by 130%. Similarly, “in the 873 rural places that experienced population growth, more than 1 in 5, or 21 percent, can attribute the entirety of population growth to immigrants.”[15] These are the realities that should contribute to a new definition of “rural.”

The term rural encompasses clashing ideals and disputed histories. For many people, like me, rural is a place of privilege.

The term rural encompasses clashing ideals and disputed histories. For many people, like me, rural is a place of privilege. It is a place we can choose to live in or not and one that offers endless beauty and unique recreational activities. For many others, it is a place of extreme poverty and one that comes with very little choice. Rural America has often been thought of as a place of freedom; freedom to live any way one pleases. However, it has also been home to slavery and the internment of thousands of Americans. Rural America is simultaneously agrarian, mono-productive, and extractive. The pastoral hills of Vermont and the oil rigged towns of West Texas both help to define rural America. It is a land of romanticism and essentialism while simultaneously a land of decline and abandonment. Ruralism is endlessly complex and ever-shifting.

New Ruralism(s)

As Landscape Architects, we need to start by promoting definitions of the rural that stand independent of the urban and include notions of diversity and progress. In other words, we must do what designers do best, turn our original doctrine on its head and create an alternate perspective. We must stop thinking about rural as simply a piece of a dying past and start envisioning diverse and innovative rural futures.

Storytelling

Next, we need to develop new methodologies for understanding the rural and working in rural communities. The go-to design processes and methodologies of our field are currently based on Eurocentric spatial aesthetics and urban needs.[i] The sexy, green-washed mass-market designs based on large data, preset scales and prescribed agendas will not benefit rural communities. Similarly, our field’s tendency towards symbols and metaphors that often lead to appropriation and/or misuse is particularly pertinent when working with rural indigenous communities for whom the land often embodies spiritual significance as well as historical trauma. Rather than cut and paste one methodology onto the other - often leading to the recolonization of land and culture - how can we start to create more nuanced processes that respond to colonial histories, resilient cultures, indigenous practices, and regenerative needs?

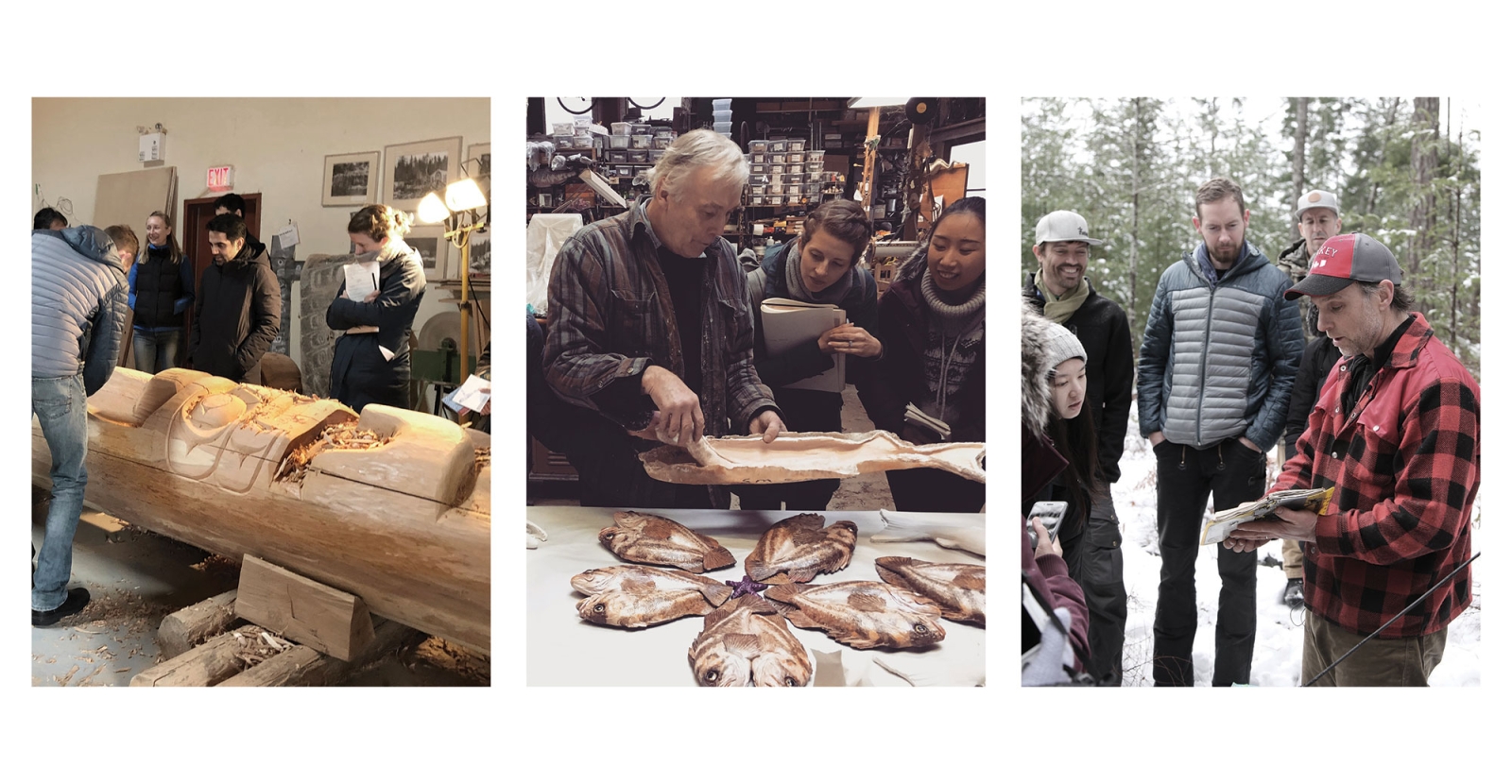

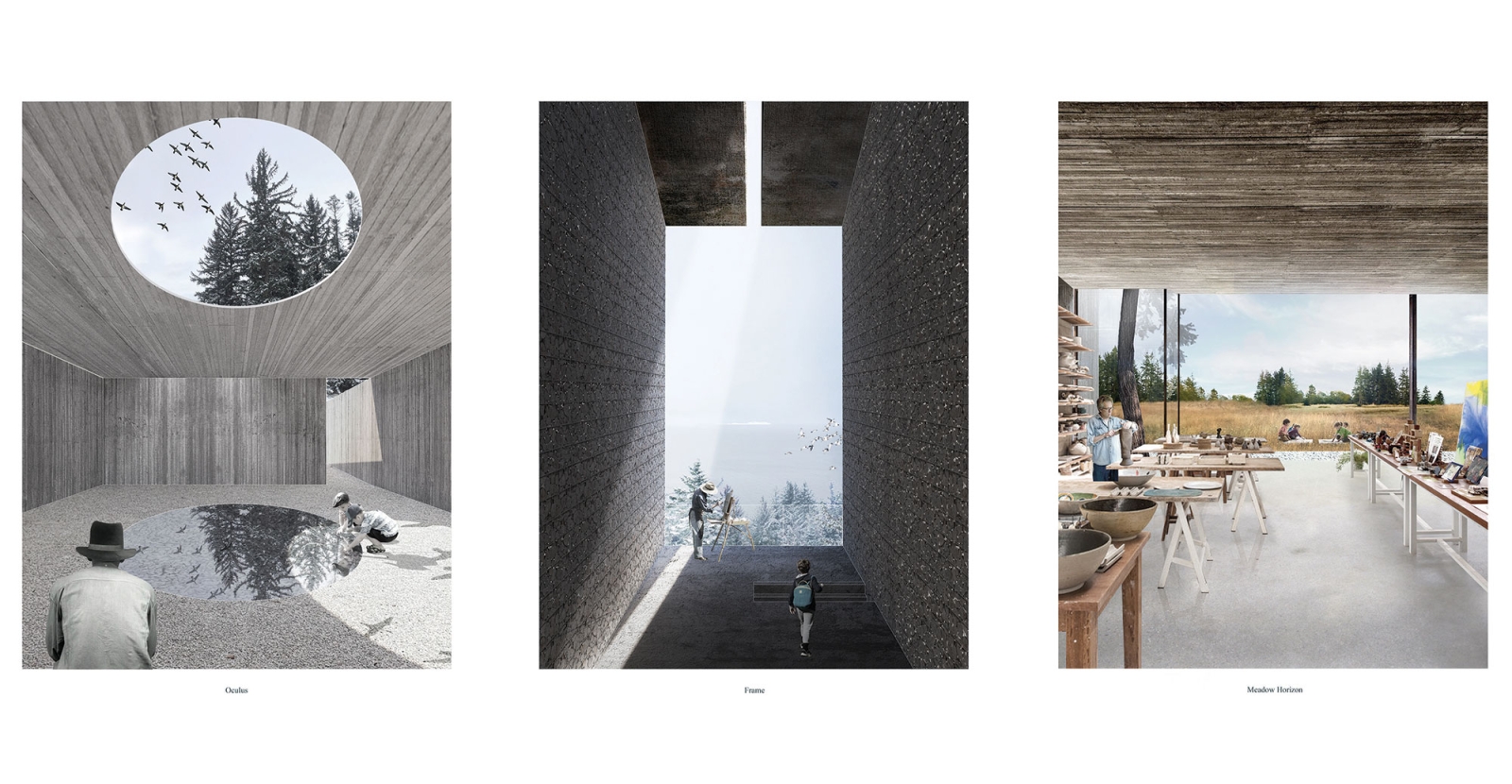

In a 2019 University of Pennsylvania Landscape Architecture studio based on Quadra Island, British Columbia - Rebecca Popowsky and Mayur Mehta worked to create a design methodology specific to ruralism. Through a partnership with Brittany Shalagan and Study Build, the studio studied the remote island through stories, interviews and oral histories.[16] Rather than conducting the typical online research and GIS mapping analysis, students traveled to the island to simply listen. They conducted interviews and spent time hiking, trail building, cooking and eating alongside residents - building a deeper understanding of the diverse skills and unique needs present on the island. They visited local research institutions, woodlots, artist’s residences, small businesses and even an elementary school, where the fourth-grade students taught the designers about the island’s watershed and how they care for it. The student designs that grew out of this studio were deeply personal and grounded in the nuanced character of the island, rather than sweeping gestures of a well-documented place. Projects ranged from collaborative maker spaces for local researchers and entrepreneurs to push innovation, to forest designs centered around community logging and mushroom harvesting, to spaces embedded in the landscape for local artists to display their work. All were meditations on Place. By focusing on conversations with locals and the smells, tastes and textures of the site, these projects built upon the local innovation and craft already present on the island and broke away from pluralistic urban methods typically employed by landscape architects.

Radical Rural Speculations

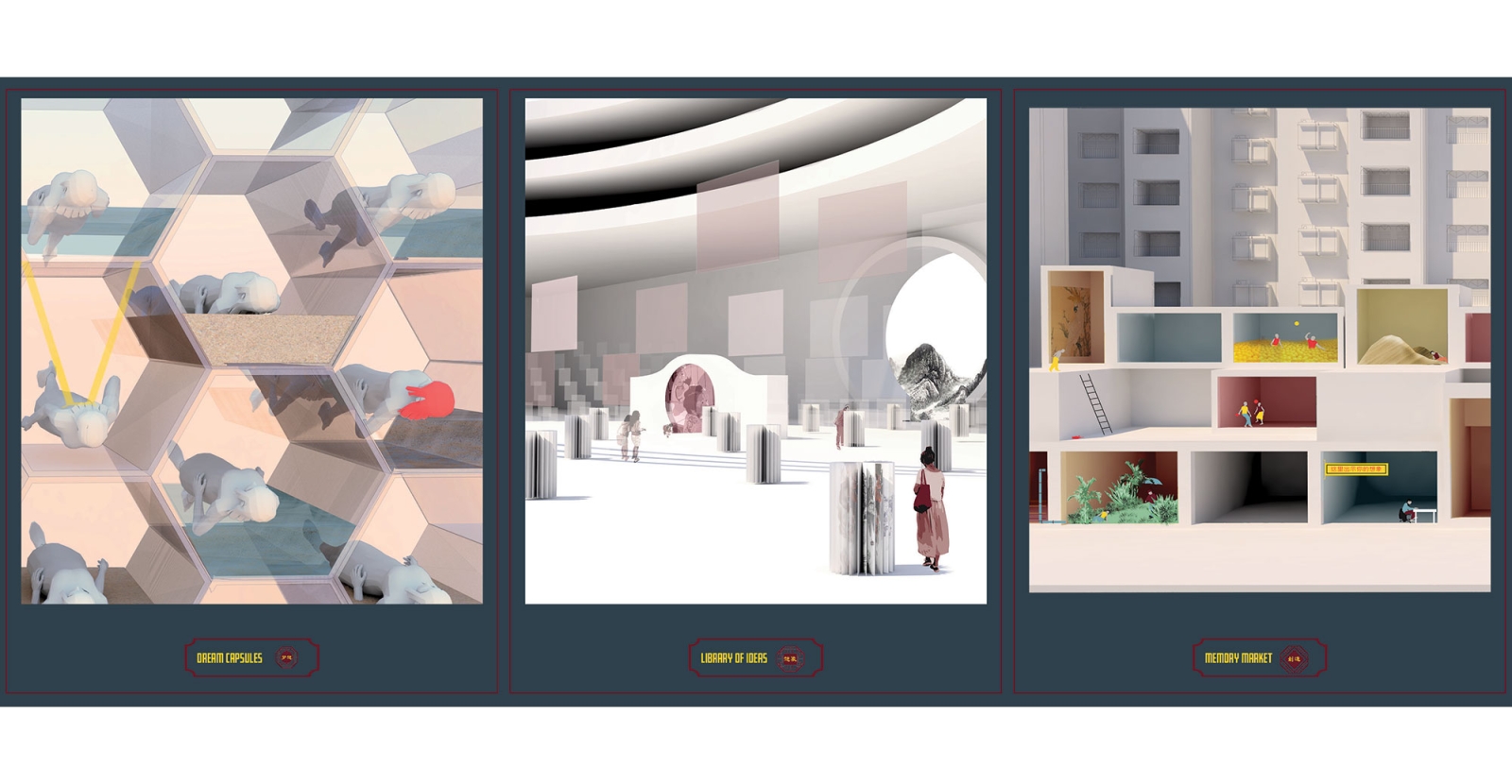

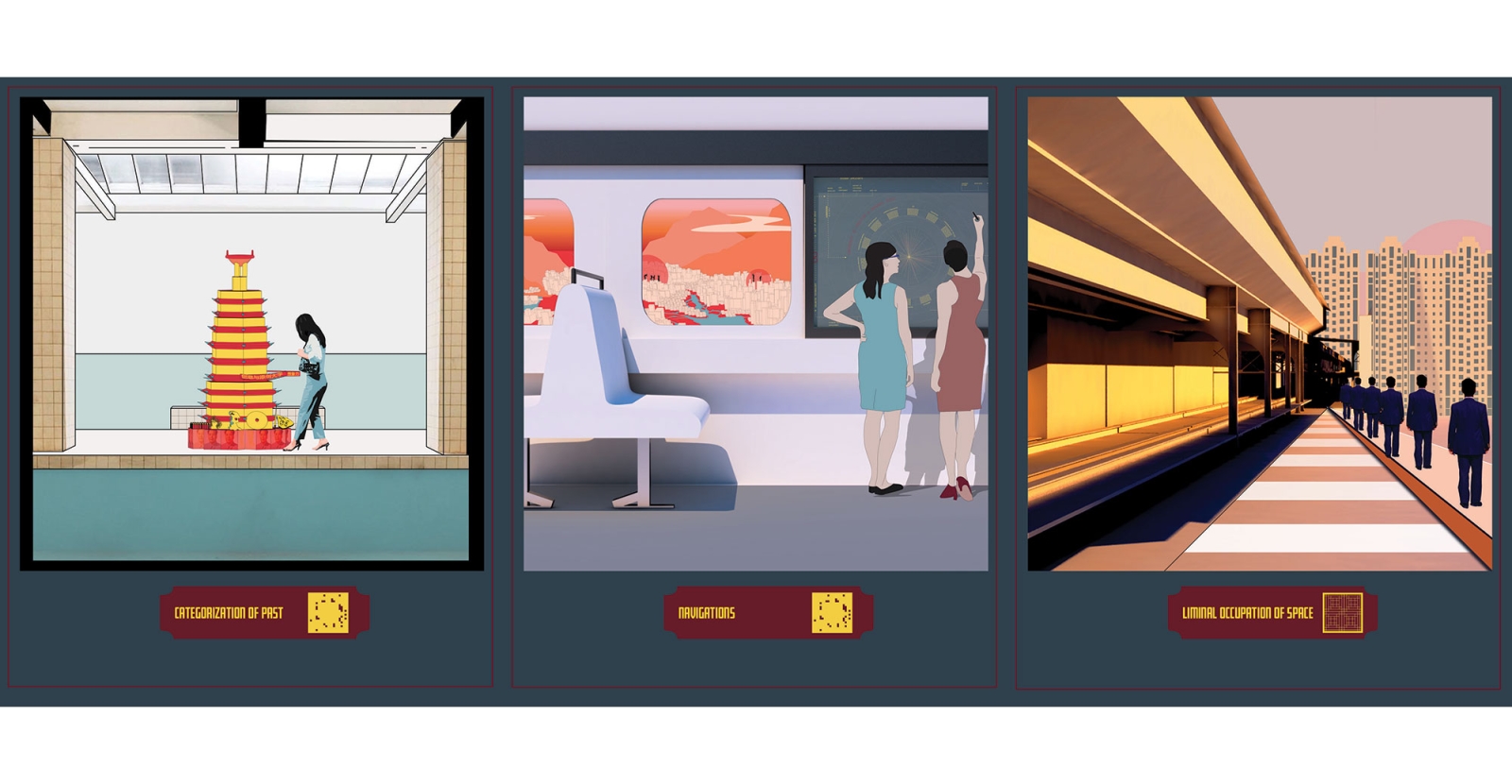

An inclusive design methodology founded on cultural sensitivity and individuals’ stories does not preclude big, bold ideas. The most exciting role for designers in this situation is to help build the space and tools that land users need to think radically, so that we can then share our skills to help illustrate, refine and develop their visions. In a past Ian McBlog entry, Anna Darling wrote about Speculative Everything, a new design methodology developed by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, which challenges designers to steer away from direct problem-solving and instead, to imagine alternative futures that are radically different from today.[17] Speculative Design, “thrives on imagination and aims to open up new perspectives on what are sometimes called wicked problems, to create spaces for discussion and debate about alternative ways of being, and to inspire and encourage people’s imaginations to flow freely.“[18] My own experience with speculative design stemmed from a University of Pennsylvania LA studio run by Chris Marcinkoski based on the Greater Bay Area of China in the year 2049. The studio was centered around the mega-region’s technologically-enabled future and explored themes such as surveillance, automation, immortality and jobless economies by imagining and illustrating novel urban futures through the lens of a character. Speculative Design enables designers to challenge norms and capture the imaginations of unknown future trajectories by operating at multiple scales and freeing ourselves of the problem-solving methods we typically depend on.

Community Driven Speculations

Speculative design has most often been applied to a hyper-urban context and due to its often-bizarre radicalism, it is a method that seems coveted by designers - forcing a top-down implementation. What if we begin to form a new method of community-driven design that harnesses the imagination of the stakeholders by guiding their local stories towards future speculation? How can storytelling and oral histories of land-users lead us to speculative and innovative designs with communities that are too often ignored, forgotten or deemed unworthy of big ideas? Ruralism needs a new methodology that is both sensitive to its diverse populations while radical enough to break through its societal association with the past. Such future-forward methodologies can and should be applied to rural areas through an inclusive approach, enabling user groups to drive the design through their own imagination. As we edge closer to community-based design methods, we need to remember that design thinking is a privilege. As most designers know too well, good design takes time and at least some sleep. If we want community-driven design, we must do what it takes to support the community to participate and drive the design - whether that means meals, monetary reimbursement, childcare, or a design process based around celebration.

Conclusion

The urban/rural gash that runs through the United States is only growing deeper, pushing urban notions of rural further and further into a backwards past. At the same time, Landscape Architects have not been shy about our overwhelming preference towards urbanism and urban forms, as we have centered our profession around urban issues. However, it is clear that while rural areas defined by census population numbers may be declining, ruralism as a spatial identity perseveres. As landscape architects begin taking on major, nation-wide proposals such as the Green New Deal, it will be essential for us to shift our attention towards rural America. This presents an opportunity to ditch the methods of our profession that aren’t serving the land-users and to pick up new methodologies that although risky, will help larger, future-forward ideas rise out of smaller, under-prioritized communities - an opportunity to harness the imagination of millions of Americans.

[1] Ian McHarg, Design with Nature Now

[2] Frederick Steiner, Healing the Earth: The Relevance of Ian McHarg’s Work for the Future - pg 83

[3] Ian McHarg, An Ecological Method for Landscape Architecture, pg 107

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, Urban and Rural Population: 1900-1990; Census 2000 Summary File 1 Table P002; 2010 Census Summary File 1 Table P2, A Century of Delineating a Changing Landscape: The Census Bureau's Urban and Rural Classification, 1910 to 2010

[5] ibid.

[6] ibid.

[7] Cloke, P. (2006). Conceptualizing rurality. In P. ClokeT. Marsden & P. Mooney The handbook of rural studies (pp. 18-28). London: SAGE Publications Ltd doi: 10.4135/9781848608016.n2

[8] Ching, B., & Creed, G. (1997). Knowing your place : rural identity and cultural hierarchy.New York: Routledge. 4

[9] Cloke, P. (2006), and Thomas, A. R. (2011). Critical rural theory : structure, space, culture. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books.

[10] Creighton, M. (1997). Consuming Rural Japan: The Marketing of Tradition and Nostalgia in

the Japanese Travel Industry; Ethnology, 36 (3): 239-254.

[11] Robertson, J. (1991). Native and Newcomer: Making and Remaking a Japanese City.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 34-36

[12] Cloke, P. (2006). Conceptualizing rurality. In P. ClokeT. Marsden & P. Mooney The handbook of rural studies (pp. 18-28). London: SAGE Publications Ltd doi: 10.4135/9781848608016.n2

[13] “Race and Ethnicity in Rural America.” Housing Assistance Council (HAC). Rural Home, Apr.

2012, www.ruralhome.org/storage/research_notes/rrn-race-and-ethnicity-web.pdf.

[15] https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/reports/2018/09/02/…

[16] https://www.study-build.com/