Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

Radical Speculations: Designing the Post-Carbon Future

The future: as of late I have become increasingly focused on this elusive and unknowable subject. So, when asked to participate in a panel of young practitioners for the “Design With Nature Now” conference at the University of Pennsylvania, I focused on the future. In particular: how we, as designers, construct the future.

The future[1]

What does this constructed future look like? A stock photo of the suburban “green” home—complete with solar panels, a rainwater harvesting system, an edible garden, and an electric car? Or is it more like The Day After Tomorrow—complete with the now-cliché images of iconic skylines destroyed by climate disaster?

Our destination[2]

As landscape architects, our work is just as much about building a vision of the future as it is about actually building. Yet how equipped are we to actually envision this future? Our current methods for constructing the future are typically master plans and renderings, which generally don’t extend beyond the bounds of the project site, let alone into a future beyond the lifespan of the project. More often than not, we are reliant on static maps and surveys of past or existing conditions, as opposed to scenarios or forecasts of what’s to come. While these methods are valuable, they perpetuate a static image of our world, which is changing with increasing rapidity.

When we do venture into the realm of the future, we focus on the ecological shifts caused by rising sea levels and species migration, relying on scientific forecasts for visions of what is probable in order to maintain our reputability. Rarely do we explore possible futures where social, political, cultural, or economic shifts (alongside the ecological) have redefined landscapes.

Our current techniques limit how radically we are able to envision the future. In order to open up our capacity to imagine alternative futures, we need to explore alternative techniques—from scenario building to science fiction to speculative design. The necessity for this imagination is growing increasingly urgent because right now others are constructing our future. Google is building cities and Amazon is planning moon colonies—and we’re designing their campuses.

Who’s designing the future?[3]

From where we stand now, the world doesn’t look so good. No matter how much we invest in solar panels or electric cars, our future will be rife with protest, struggle, and resistance, because the shift to a post-carbon future will be an inescapably radical upheaval. And yet the futures landscape architects are drawing are as benign as stock photos. To begin to construct alternative futures, we must move beyond what’s merely probable and start moving into the realm of what’s possible. I propose here a few ideas that we, the rising generation of landscape architects, might take as starting points for the exploration of radical futures.

1 ~ Mobilizing for Just Transitions

Building the post-carbon world is not a job for designers alone. As Damian White, professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, describes in his essay “Just Transitions/Design for Transitions,” it is essential for designers to build coalitions between labor and politics to create the “political and policy imaginaries for thinking about the complex and fraught alliances that will have to be built to move just post-carbon transitions forward.” Through these partnerships we can develop new outlets for the production and presentation of radical design work and catalyze dialogues about the direction of change.[4]

It will also be essential for designers to better articulate where, and for whom, we are working (since the climate crisis will disproportionately affect some communities), in order to craft partnerships based on mutual values. Furthermore, we must take a more active political role in order to ensure these dialogues do not remain constrained within educational institutions or the design professions. Advocating for local and federal policies, such as the Green New Deal, that have the capacity to instigate these partnerships is the first step in mobilizing towards an alternative future.

2 ~ Seeking out alternatives to client-based practice.

Can client-based work support the radical design and research that we need in order to move toward alternative futures? One potential example of a different path is OLIN Labs, the research wing of the design studio, which is developing imaginative technologies and practices such as “Soil-less Soil,” a compound soil system incorporating recycled glass as an aggregate.[5] However, this model may not prove to be widely replicable due to its reliance on a consistent stream of funding from high-paying clients.

Other design practices have provided different examples of novel funding sources. For instance, DLANDstudio has sought out grant funding for their projects, while MASS Design Group operates with a nonprofit structure. But as our generation begins to develop practices, we must continue to envision new alternatives to client-based work—otherwise, our connection to traditional, capitalist funding models will keep us from moving into a more radical future.

Such new funding models will enable designers to be more active in choosing who we are designing for, allowing us to support those hit hardest by the climate crisis, poverty, and health inequality—instead of remaining a profession serving only the wealthiest minority.

3 ~ Experimenting with speculative design

Finally, we come to speculative design and visualizing the future.

As Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby write, “This form of design thrives on imagination and aims to open up new perspectives on what are sometimes called wicked problems, to create spaces for discussion and debate about alternative ways of being, and to inspire and encourage people’s imaginations to flow freely. Design speculations can act as a catalyst for collectively redefining our relationship to reality.” In light of this framework, I present three speculative projects for consideration:

The first example is the “Oceanix City” project by Bjarke Ingels Group—ostensibly a design for a floating village, safe from sea level rise and storm surge. If the project succeeds, it is by demonstrating how speculative design can generate conversation—because it has surely been the focus of debate, forcing viewers to ask whether this is really how we want to invest our precious time and money in fighting the climate crisis.

I hope not. Oceanix City projects an image of the future that is isolated and static. And it’s drawn in such a way as to make one forget the kind of social and economic inequality required to create a city like this: superficially glamorous and blithely devoid of context or culture. Yet despite these failures, at the very least having these speculative images in front of us enables a critical conversation about the future.

Thoughts from aboard Oceanix[6]

The second project is “Bight: Coastal Urbanism,” a proposal for RPA’s 4th Regional Plan by Rafi Segal and DLANDstudio. Bight’s designers establish credibility and ground their work by using spatially specific imagery and sea level rise projections, yet their project stands out because it highlights socio-cultural shifts concurrently with relevant design interventions. Rather than try to masterplan the whole area, they describe moments in this future place, through interviews with residents and time-lapse perspectives of public and domestic spaces. Through these snapshots, they are able to capture the political, social, and economic changes accompanying radical urban and ecological shifts, describing a way of living more than a singular design intervention.

Subtleties of Bight[7]

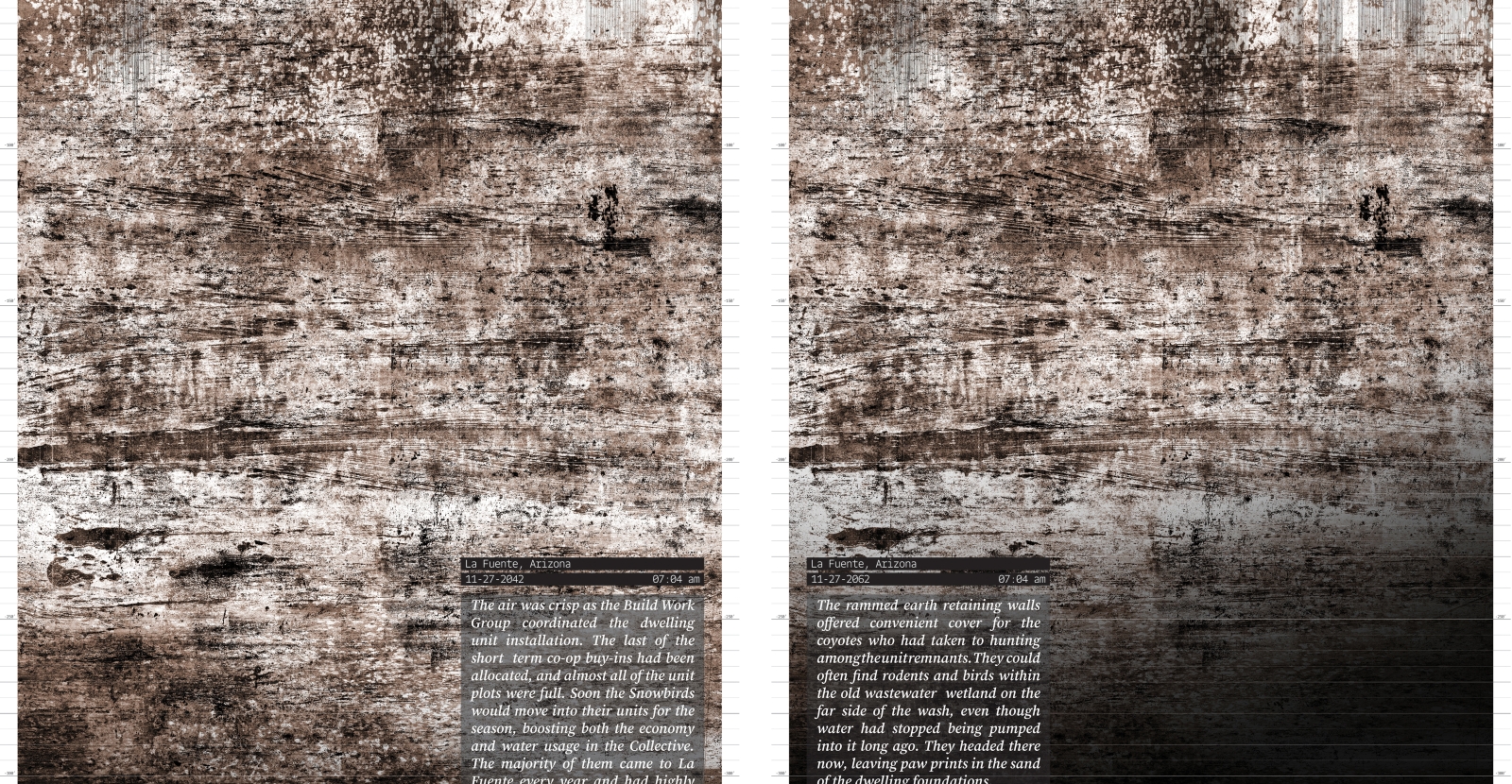

The third project is my own foray into the world of speculative design, in the form of my MLA thesis. “Ground/Surface: Alternative Water Futures” explores an alternative vision of living within the future limits of groundwater withdrawal in southwest Arizona’s San Pedro River basin. In opposition to the fixed, sprawling, overwatered developments currently being planned for the basin—which contains the last free-flowing river in the Southwest—“Ground/Surface” imagines a future where water withdrawal shapes the very dynamics of life in the desert.[8]

In this alternative world, shifts in the legal structure of groundwater regulation catalyze the formation of migratory communities constructed around the communal necessity of water use. The design explores the methods these settlements use to conserve, celebrate, and recharge groundwater; at the same time, it describes novel structures of governance, the “water committees” created to manage water allocation and determine how long each settlement can occupy a location. My goals for this work were twofold: to design physical interventions that transform the way people understand and interact with groundwater; and to spark a discussion about how people might live within the limited resources available in the future.[9]

“Ground/Surface” habitation and regeneration stills

The more that we, both as a profession and as individuals, practice speculative design, the better we will be at critiquing it—and, hopefully, at resisting the seduction of utopian graphics, which convey, at best, benign images, and at worst, harmful perpetuations of social inequity. In hopes of improving our ability to critique and create alternative futures I have compiled the techniques that I’ve so far found to be fruitful for exploring speculative design:

- Establish a specific and clear research question (to avoid creating a generic green utopia).

- Build a narrative describing the radical shifts that were required to bring about the change in question (so the audience understands what precipitated this speculative future).

- Provide snapshots into the future, instead of attempting to design this alternative world in all its aspects (the future is inherently indeterminate, so it’s futile to try to describe it in totality).

- Respond to a specific, existing, site—including politics, public figures, culture, and ecology (if the project extends too far beyond what’s recognizable, it moves beyond speculative design into the realm of science fiction).

- Offer insights into the broader cultural aspects of this speculative future: e.g., altered politics, new social values and economic structures, or demographic transitions (landscape and culture are intertwined; one cannot radically shift without the other).

- Use a tone that makes clear the speculative design is not a literal proposal but rather a thought experiment (in order to focus conversation on the possible, not the impossible; and to avoid the distraction of glossy imagery lacking substance).

Damian White writes: “Just transitions. . . are not going to emerge without social protest and revolt, labor stoppages and mobilized class forces seeking to take power at every level to undercut and ultimately shut down fossil capitalism. The day after the demonstration, a just post-carbon world that actively improves people’s lives still has to be imagined and built, fabricated and realized, institutionalized and sustained by public support and ongoing engagement.”[10]

However, we don’t have to wait until the day after the demonstration to begin to construct the post-carbon future. We can start today. Imagine if “firms” in the future all take on this mantle—if designers learn to find work by creating alliances between politics, labor, and creativity, and build multiplicities of alternative futures instead of competing over private clients and their money. This is how we begin to meet our radical challenges: with radical proposals for how to live in the future to come.

[1] Isaac Cordal, Follow the Leaders, Berlin, 2011.

[2] Collage elements from John Pacer, illustration in Meir Rinde, “Imagining a Postcarbon Future,” Distillations (blog), Science History Institute, October 11, 2016, sciencehistory.org/distillations/imagining-a-postcarbon-future; and trailer for The Day After Tomorrow, directed by Roland Emmerich (Los Angeles: 20th Century Fox, 2004), YouTube video, 2:08, youtube.com/watch?v=Ku_IseK3xTc.

[3] Rendering by Snøhetta and Heatherwick Studio of proposed Quayside development in Toronto by Alphabet company Sidewalk Labs; rendering by Blue Origin of hypothetical space settlement.

[4] Damian White, “Just Transitions/Design for Transitions: Preliminary Notes on a Design Politics for a Green New Deal,” Capitalism, Nature, Socialism (2019).

[5] More information regarding OLIN Labs and the Soil-less Soil project is accessible at olinlabs.com.

[6] Renderings by Bjarke Ingels Group of “Oceanix City,” with annotations by author.

[7] Images by DLANDstudio and Rafi Segal Architecture and Urbanism from “Bight: Coastal Urbanism.”

[8] An example of current development strategies is the ostensibly Tuscan-inspired “Villages at Vigneto” proposal, a plan which would double the current population of the San Pedro River basin. Imagery supporting this proposal can be seen at vignetoaz.com.

[9] The thesis was advised by Ellen Neises and Sean Burkholder; more information can be found at groundsurface.cargocollective.com.

[10] Damian White, “Just Transitions/Design for Transitions.”