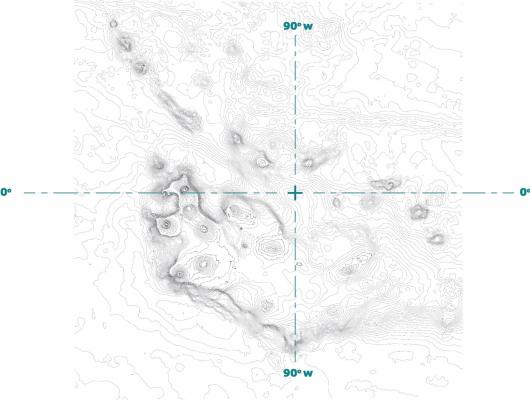

Galápagos Islands

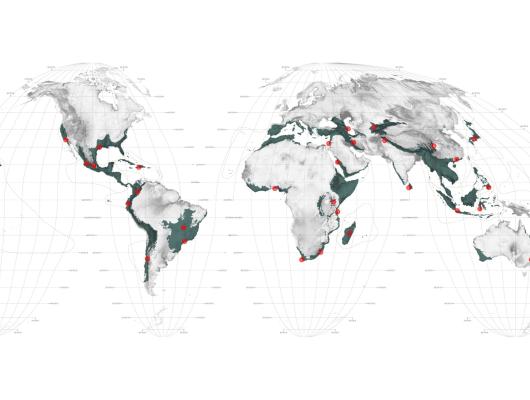

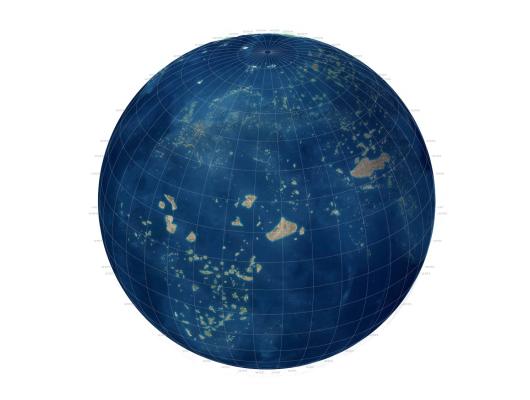

The enormous amount of attention that has been paid to the natural environment of the Galápagos has not been extended to the developable areas. There is little or no long-term planning. With an economy dependent almost solely on water-based activities—tourism and fishing—climate change could adversely impact waterfront use and access, and more volatile weather patterns will have wide-ranging effects on the flora and fauna. An immediately pressing issue is to consider where an increasing population will live. At its current growth rate, San Cristobal’s population could double in just over ten years, and development is already butting up against the Galápagos National Park border. The first phase of this project involved taking design students to San Cristobal Island to develop individual design proposals. The second phase utilized these proposals to compile a landscape framework for directing development. The third, upcoming phase, will use this work to do outreach on the islands in collaboration with colleagues from Quito, Ecuador.