Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

Breaking the Debris Cycle: The Case for Deconstruction

The prevailing wisdom in domestic climate adaptation policy is to await a state of abandonment and destruction—a crisis state. I propose a paradigm shift. One based on the preemptive disassembly of the material elements of our day-to-day lives. Managed retreat plans must create the space and time to carefully reconcile with change by deciding what will stay and what will depart, along with the community, in the move to less vulnerable land. This is both a matter of avoiding loss—preventing the dissolution of a town into sterile FEMA-designated debris categories—and of transforming the way society reckons with the immediacy of the climate crisis.

From Debris to Material Legacy

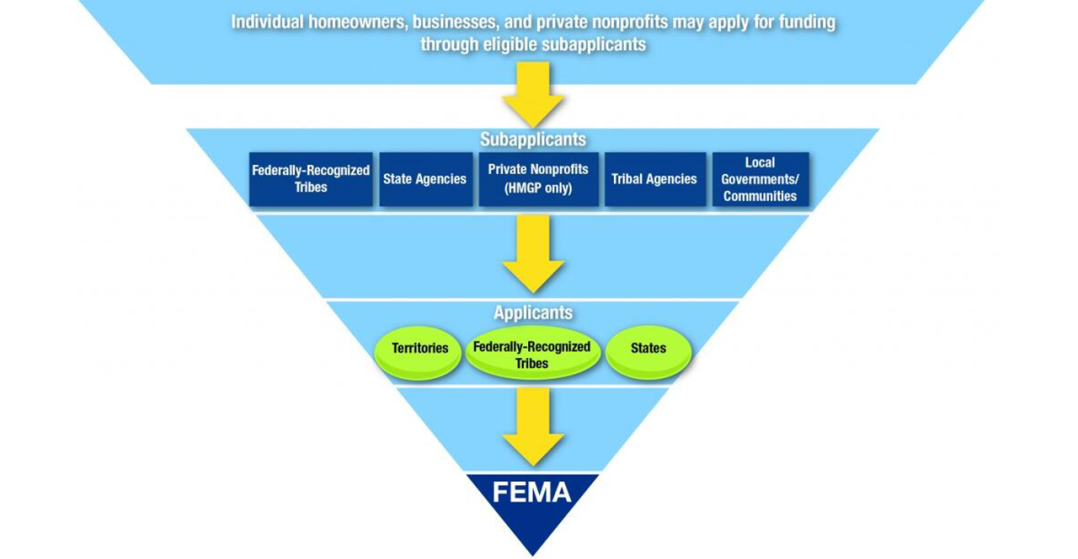

Currently, through both HUD’s and FEMA’s funding structures, homeowners receive a pre-disaster fair market value home buyout and move elsewhere. Their home is most likely demolished, and components are sent to a landfill. Homeowners usually receive this funding only because their communities were victims of past destructive disasters. FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (provided under the Flood Mitigation Assistance Grant Program) only provides funding to states which are victims of a presidentially declared “major disaster,” to use the language from the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. For homeowners who experience chronic flooding that may not qualify as a “disaster,” the chance to sell a home in a floodplain may only come after it is already in dire condition.

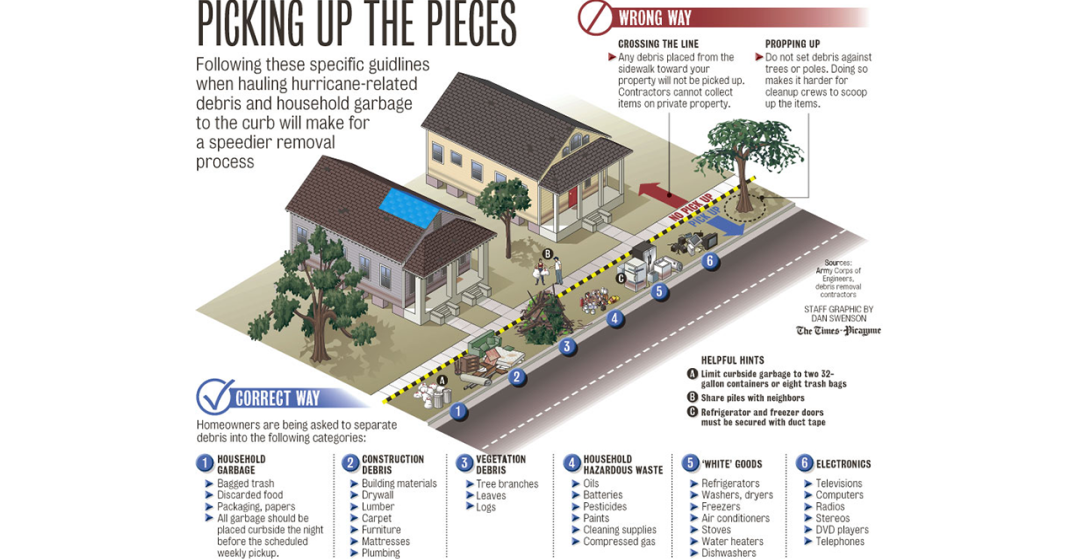

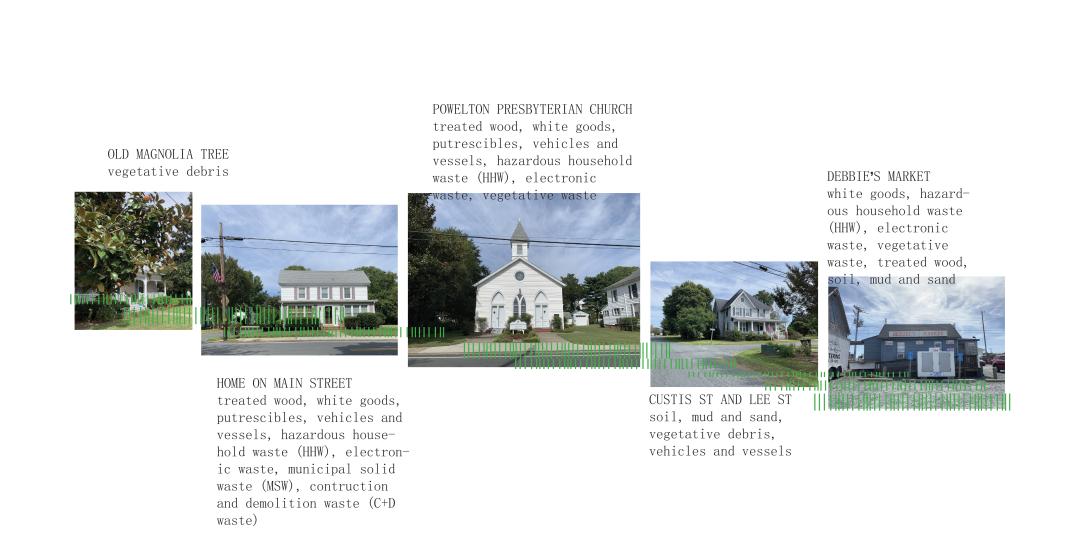

Under the current debris paradigm, we manage the loss of material by sorting debris according to FEMA-designated categories. The old wooden mantelpiece becomes construction debris (abbreviated “C&D,” for “Construction and Demolition”); the magnolia tree in the front yard is vegetative waste. Each element is hastily sorted and trucked away. And although FEMA’s website has a set of guidelines dictating procedures for material management and environmental hazards, most waste is inappropriately managed in a time of crisis, leading to long-term environmental hazards due to soils and groundwater contamination.

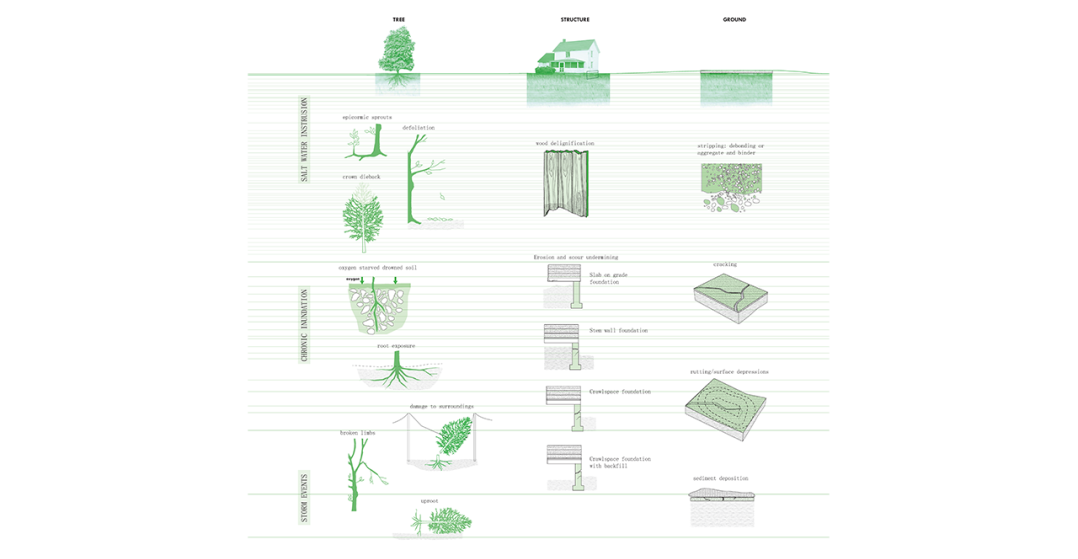

Beyond the unsentimental nature of debris management, the disassembly process itself can expand the legibility of chronic inundation by framing sea level rise as a form of material distress signal. While landscape architects and planners live by NOAA’s sea level rise data, projected onto maps in ethereal blue hues, the lived reality of sea level rise can differ wildly and for any number of reasons. Depending on the type of foundation your home is built on, what your driveway is made out of, or which tree is growing in your front yard, you may experience the effects of those map projections years before your neighborhood is highlighted in that fluorescent blue.

Material distress provides a new index that places an emphasis on preserving the physical integrity of your home for recycling and reuse. Viewing your home as an asset, the condition of which will inform the timing of your decision to deconstruct, is a huge step forward from our current floodplain buyout system. The materials are transformed from liabilities to unload into an asset to preserve.

The Building Industry

Deconstruction as a managed retreat strategy has the potential to challenge two outdated systems in the United States: the building industry’s lifecycle and the federal floodplain buyout program. One third of the overall waste in the United States comes from the building industry, with approximately seven pounds of waste produced per square foot of new construction and seventy pounds per square foot of demolition and renovation. Building also lags significantly behind other industries. Most cars, for example, contain over 70 percent recycled material, while the average new building is comprised of just around 1 percent. While adaptation and mitigation strategies often end up at odds, changing these building practices could be a crucial step toward decarbonizing adaptation practices.

Much of the estimated 3 trillion board feet of lumber harvested in the US since 1900 still resides in buildings; most of it is high quality lumber perfect for recycling or direct reuse.[1] However, due to the lack of incentives for materials recovery and the high up-front costs of deconstruction, demolition remains the dominant removal method. Consequently, deconstruction experts and material recyclers and resellers remain a very small portion of the demolition industry.[2]

Deconstruction represents a significant opportunity for investment in this sector through federal and state subsidies—not only to deconstruction specialists, material resellers, and recycled material vendors, but also to homeowners wary of the expense of deconstruction. What if homeowners were able to recoup the material value in addition to the pre-disaster fair market value of their home in a buyout scenario? If homeowners begin to appreciate their home’s stored assets, they may choose to leave before they risk destruction in a future storm event.

Subsidizing the value of these materials themselves would also increase the value of deconstruction to a homeowner in a floodplain. The US has a rich history of subsidizing virgin materials, from the timber industry’s write-offs for forest management and reforestation costs to below-cost mining leases. These virgin material industries also benefit from exemptions from environmental laws and rarely pay the cost of their products’ externalities.[3] There is no reason why subsidies like this should not extend to—or be replaced by—recycled materials.

Floodplain Buyouts

FEMA and HUD funnel money through states to local communities who, in turn, distribute the money to individual homeowners, with separate application processes and bureaucracies along the way. Yes, it is complicated. Although this is not the place for a full critique of the hell that is the reverse pyramid/multi-level federal funding structure, what I can say is that this process allows room for inequity and subjectivity in the allocation of funds.

Building off the work of A.R. Siders, whose research points out the unjust implications of current buyout program structures, I’ll frame this discussion in terms of deconstruction. One factor in determining the allocation of funding under FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program is a cost-benefit analysis (“CBA”). This CBA is highly value-laden and excludes many benefits and costs, especially those which are hard to monetize. For example, cost recuperation of home or yard materials is not yet included in this CBA, nor are the costs of emergency response and utility maintenance.[4]

Compounding this lack of a comprehensive fund allocation assessment system is the reductive underlying logic behind these grant programs, which contends that the federal government should only fund buyouts in areas already “devastated” by an official “disaster.” Were it to account for the full spectrum of benefits accruing from pre-destruction or pre-crisis retreat, perhaps FEMA’s CBA would favor funding early-state repetitive loss properties that would leave homeowners eligible for deconstruction. This type of systemic reform could make floodplain buyouts a viable, proactive strategy for managing coastal retreat, rather than a last-case scenario for picking up the pieces after a destructive event.

Designing a deconstruction cycle

So what does this all mean for designers? It is our role to design the spatial reality of any material legacy paradigm. This role will require rethinking the spaces in which we distribute and collect our waste as well as designing what will be left behind on this land after deconstruction. And it will require considering not only the monetary benefits to deconstruction which aid the advancement of policy, but also the highly sentimental nature of our material lives. Pre-disaster retreat allows people time to sort and collect household objects that might be reduced to waste in a crisis; and it allows them time to plan and make long-term choices rather than simply reacting in the face of immediate crises.

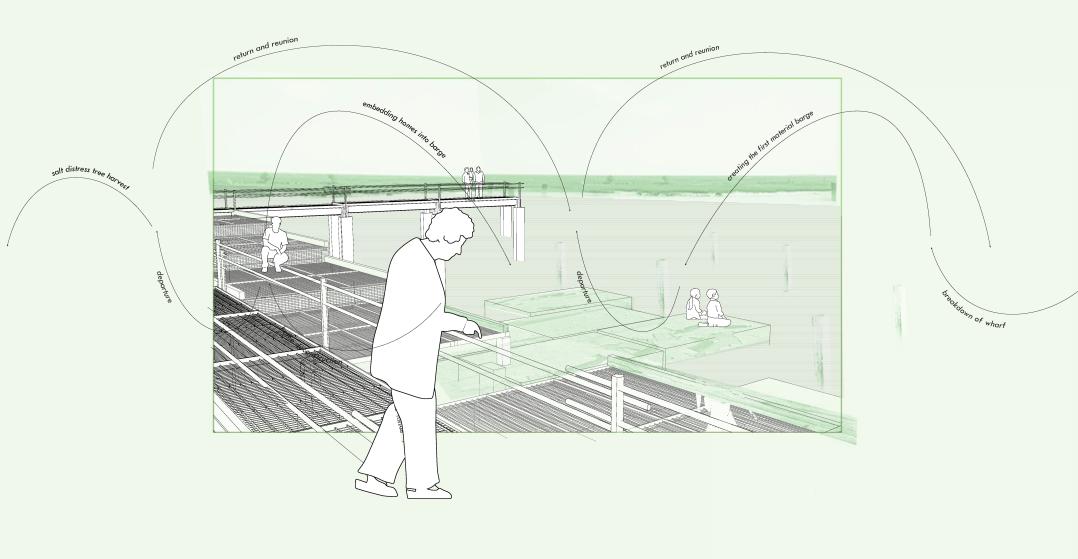

Designers have the opportunity to intervene spatially during this crucial shift from cleaning up after a crisis to engaging proactively beforehand. How will these spaces differ from our traditional waste disposal and logistics landscapes? They will be spaces in which to convene; spaces to return to; and spaces to reconcile with big change.

Given the chance to speculate on this in the context of a design studio, I first looked to existing examples of “waste spaces.” In Kamikatsu, a small town in Tokushima, Japan, the Hibigaya Waste Station is at the heart of the town’s radical shift toward reducing its waste output. The airy open shelter occupies the site of a former incinerator; now residents sort waste in this welcoming space, which resembles a covered market more than an industrial facility.

On Brooklyn’s industrial waterfront, Selldorf Architects’ Sunset Park Material Recovery Facility sets a new precedent for waste space. The facility extends out over the water, receiving recycling materials by barge and thus eliminating vehicular travel in and out of the surrounding neighborhood. Here the recycling process becomes a form of spectacle, with spaces for visitors to watch the entire process unfold.

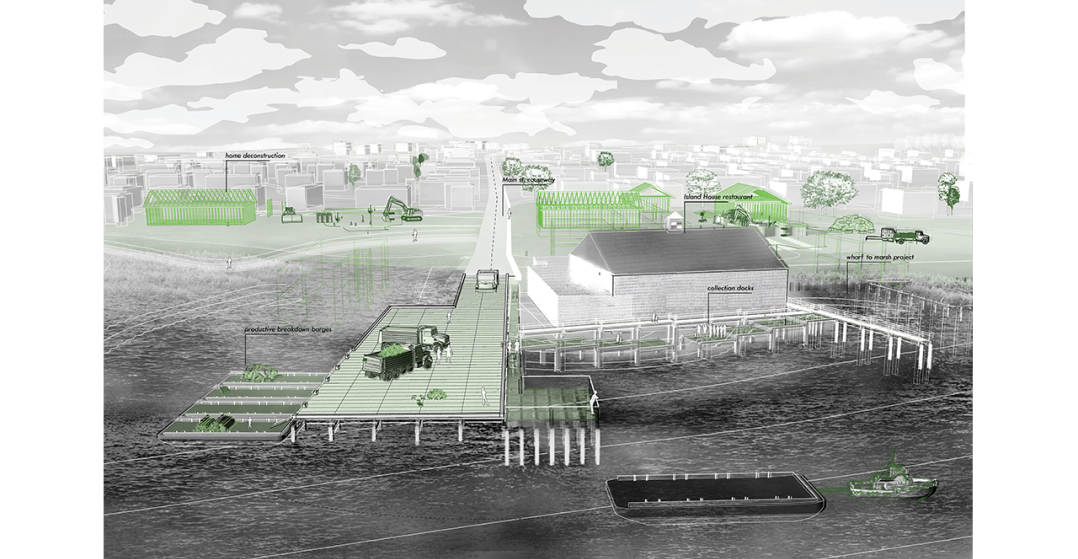

My own work lands in Wachapreague, Virginia—a small town on the Eastern Shore, projected to be mostly inundated year-round by 2080. This reality calls for a strategic planned retreat, allowing for departure with dignity. I proposed coupling home deconstruction with a buyout program to incentivize pre-disaster retreat and material recycling. Under this system, the homeowner gains both monetary and personal benefits from deconstructing their home on their own terms. At the county scale, jobs are created, and C&D waste is diverted from limited landfill space. At the planetary scale, this material reuse cycle mitigates future carbon emissions from the energy required to make new building materials.

These multiscalar processes telescope onto the site of the wharf at the end of Wachapreague’s Main Street. Currently the location of the town’s only restaurant, the site becomes a hybrid deconstruction depot and gathering space. The overall facility is divided into two broad programmatic categories. On one side, borrowing from Selldorf’s recycling facility, barges deposit salvaged material retrieved from area homes and the greater landscape, to be sorted into categories for reuse. At the same time, the other side of the facility offers a passive public space for residents to convene and reunite, even after many have moved away. It is here where we are tasked with handling the highly personal connection we have to our material lives. Here the sleek and efficient sorting of materials is abandoned for messier and more personal assemblages. Perhaps particular objects might be physically embedded into additions to the docks; perhaps residents might create waterfront memorials of material from one particular block or one local church.

While this speculative project does not claim to account for all of the variables and spatial dimensions of the complex policy and logistical changes I have called for in this essay, it suggests a first step in envisioning what future places of active retreat might actually look like. Retreat can be more than just a process of rapid destruction or abandonment—and might even become a truly generative framework—if policies and incentives change to give deconstruction real space in the larger discussion of climate adaptation.

[1] C. J. Kibert and J. L. Languell, “Implementing deconstruction in Florida: Materials reuse issues, disassembly techniques, economics and policy,” Tallahassee: Florida Center for Solid and Hazardous Waste Management, 2013.

[2] M. Grothe and D. Neun, “A report on the feasibility of deconstruction: An investigation of deconstruction activity in four cities,” Washington: US Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research, 2002.

[3] Kibert and Languell, “Implementing deconstruction in Florida” (2000).

[4] A. R. Siders, “Social justice implications of US managed retreat buyout programs,” Climatic change, no. 152(2) (2019), 239–257.