Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

Who are we designing for in the future?

Landscape architects often pitch our profession as a public agency. We believe—at least most of us believe—that we are endeavoring, with our time and intelligence, to create a better, healthier, and more vibrant version of public life. But what is the essence of “public” for us? This is a question we need to ask ourselves. Does “public” simply encompass the group of users of the spaces we design? Or does it manifest something more aspirational: the courage and responsibility to engage the sophisticated, yet hardly articulated, connections between our vision and what is actually understood by individuals?

The gap between our understandings of landscape architecture

During an internship as a landscape designer in Munich two years ago, I took an Uber and chatted with the driver. He asked me what I did, and I answered: “landscape architecture.” He was confused about it, so I explained that I design landscapes. His response: “do you design the mountains or the rivers?”

We all admit that a portion of the public doesn’t know much about landscape architecture; but have we ever asked ourselves: do we know the public enough?

We design for people, most of whom we don’t know and will probably never have the chance to meet. And yet the success of our work relies on keen judgment of the public—which is composed of unique individuals.

Gardening and landscaping: A field becoming more and more public

Landscape architecture, partially derived from gardening, was originally a practice purely benefiting the powerful and wealthy. But that has not remained the case in the modern age. Compelled both by transformations in social structures and a new ethos of serving the public, designers like Frederick Law Olmsted and Ian McHarg navigated the boundary of the field and enlarged the scope of it to address a broader audience.

Over the years, the efforts of generations of designers have made our work more and more visible to the general public. The contemporary topics occupying our field, like climate change and urbanization, demand a tighter engagement with the magnitude of the public at a global scale. These challenges urge landscape architects to be critical about what constitutes and what shapes the publics we face.

The public we know

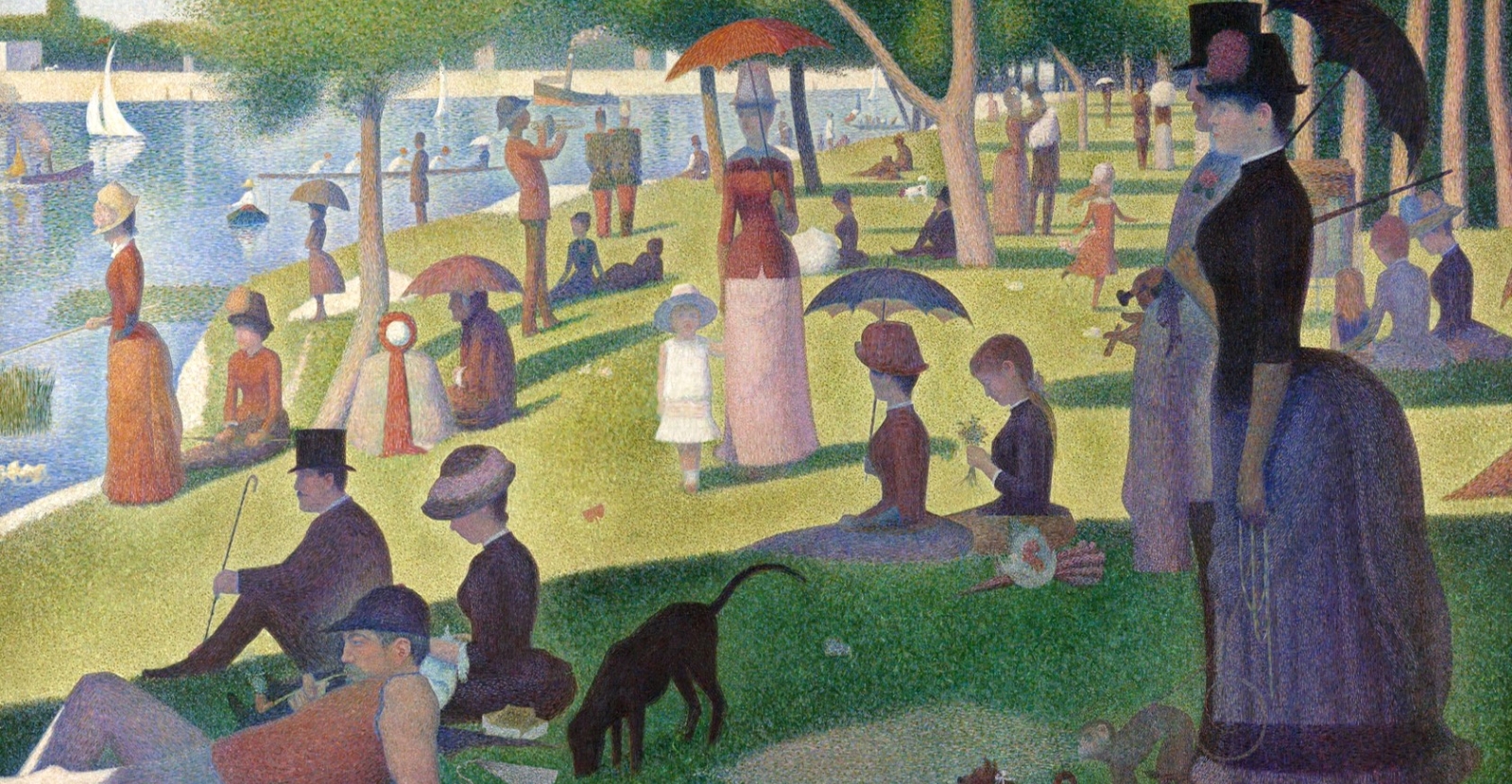

Portraits of public spaces and their inhabitants have barely changed in centuries. Open spaces have continued to be depicted as beautiful, pastoral, and protected islands in the city for leisure and recreation to take place. Under that continuity of imagery lies the belief that we, the field of landscape architecture, understand how people appreciate public spaces—and that this is not going to change in the future. Our expertise is underlain by that faith in knowing the public.

The public we don’t know

But recreation, leisure, and pastoral aesthetics are only minor components of the reality of the “public” that we can engage. As Hannah Arendt argued, publics are formed only in the presence of others, which indicates the significance of public spaces as places where the appearance of people constitutes the reality of a society.

The word “public” is derived from “of the people,” and is inextricable from politics. In many ways, the performances and interactions of people in public spaces are reflections of the social, political, economic, and technological conditions of a society.

Public spaces across the world are hosts to significant moments that go beyond their designers’ original agendas. Political protests, informal occupations, and other forms of public use reveal the potential for undesignated types of interactions between the public and public spaces. Without a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the public, such uses will remain outside designers’ vision.

The public in the future

Beyond observing current and ongoing phenomena, speculation into the future of public spaces requires us to imagine the future of individuals. As we enter the Anthropocene, we are embracing a world with radically dynamic demographic conditions. Taking the United States as an example: current population projections predict an increase of one hundred million citizens in less than fifty years, with radically changing age and racial compositions.

There is evidence of psychological-behavioral and technological trends in this new generation that might shape the new landscape of public spaces. Games like Pokémon Go give us a hint of a future world where physical space and digital worlds built for communication, social networking, and fun are blended together.

Moving into this future, how do we design for a public that we know less and less about through a traditional lens?

The public we work with

In most of the practice of landscape architecture, we don’t work directly with the public. We need a client, a mediator, usually private or public agencies, both representing the public in working with us and representing us in communication with the public. The question is whether they can speak for the broader audience given the fact that a lot of the people from such agencies share similar backgrounds, with each other and with the designers themselves.

Public meetings and charettes are windows for designers to understand and engage the public directly. However, these engagement methods can lack creativity. The agendas of public meetings, the composition of the charette participants, the media designers use to present their ideas—all these ingredients are analogous and provide little ground for a heterogenous understanding of the public. This is definitely an area that needs more thought, intelligence, experimentation, and exploration.

Working with the public in the future?

Moving into the future, we need to be humble and recognize the importance of shared vision between us and the public. We need to equip ourselves to identify the transforming public through new lenses of communication, both within and without our physical design work.

Step 1: Get used to a bigger audience

In our current pedagogical approach, students only learn to be comfortable with presenting work to a small and intimate group of people, and to cope with questions from people who are either familiar with their work or with their design language.

Should our professional education expose young designers to a larger and diverse group of voices and teach them to communicate their own design visions with those voices? Should it encourage them to develop design methodologies that are more flexible and open to different perspectives?

Step 2: Speculate into the future of the public

Speculating into the future of the public is an exercise of designing within newly constructed cultural, political, and technological contexts. This frees design from being too purely solution-oriented, thus allowing it to be less restricted by traditional understandings of the public and instead to focus on understanding a transformed public and implementing design creativity. This will allow designers to tap into, and better prepare for, different trajectories of the public into the future.

Step 3: Learn from those who understand the public

There is much collaboration between landscape architects and environmental engineers and ecologists. This history of collaboration has successfully transformed the scope of landscape architecture. If we look to other fields of knowledge, could it be just as transformative to learn from sociologists, anthropologists, public health scholars, and psychologists—to better understand who we are designing for in the future?