Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

Stories of Space in Times of Quarantine

Europe’s Last Plague

May 25, 1720. The Grand Saint-Antoine, a three-masted French merchant ship, sails into the port of Marseille on the southern coast of France. Its journey has been troubled: nine passengers have died since departing from Lebanon two months earlier. Following protocols designed to prevent disease outbreaks, Marseille’s health bureau orders the ship, its passengers, and its cargo of precious silks to be held in quarantine on a nearby island. In a notable breach of protocol, however, the bureau allows the early transfer of the cargo to the mainland—a fatal decision, made under pressure from silk merchants who want to bring the goods quickly to market.

June 20, 1720. A woman dies abruptly in downtown Marseille, an area of narrow streets and dense housing. She is the first victim of community transmission of the Great Plague of Marseille, a pandemic of bubonic plague caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. By the middle of August, more than one thousand individuals are dying every day. By now, the wealthiest have fled, along with many government officials. Bodies are left on the streets, and prisoners are forced to carry them toward mass graves.

March 1721. Fearing the spread of the pandemic, King Louis XV sends thirty thousand soldiers to enforce a strict quarantine over the entire region. Fifty miles north of Marseille, he requisitions local villagers to build a seventeen-mile-long drystone wall to prevent escape. Despite these efforts, the plague kills one hundred thousand people over the course of two years: fifty thousand in Marseille—half the city’s population—and another fifty thousand in the surrounding provinces. It is Europe’s last major outbreak of plague.

The legacy of the plague in Marseille is complicated. Street names and public sculptures honor the dead. Every year the Basilica of the Sacred Heart honors the anniversary of a promise made by the city council in 1722 to hold a special mass every year, in perpetuity, if the plague spared the city. And the foundations of the drystone wall still stand to the north of the city, now branded the mur de la peste—the “plague wall”—by regional hiking guides.

The wall and the ceremony remain as traces of a society’s attempts to restructure its relations with its environment and its diseases: the church service through an act of imagination, and the wall through the reorganization of space. Yet they betray the fact that Marseille’s greatest trauma never prompted a comprehensive reevaluation of its urban fabric: no Haussmann-like boulevards to bring fresh air and water into the dense urban core; no new sanitary practices or governance strategies; just business as usual, but with a new annual mass. The story of Marseille helps us interrogate our present situation. Beyond memorials and rhetoric, what will be the legacy of COVID-19? How will it restructure our societal narratives and the ways we manage space? How will the quality of our attention now, in the midst of crisis, shape this future?

Above, stained glass window, in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Marseille, depicting the city council's vow to hold annual masses, in perpetuity, in hopes of being spared from the plague. Below, the mur de la peste—the "plague wall" of Louis XV.

Stories of Disease, Stories of Culture

Pandemics are ancient—as old as human culture itself. Wherever they have struck, they have challenged humans to reevaluate their relations to their environment—as well as the cultural myths that underly these relations. In the face of crisis, these myths—the stories we tell about ourselves—can act as foundations for resilience just as they can constitute sources of vulnerability.

At the “Designing the Green New Deal” conference in Philadelphia in the fall of 2019, the writer and activist Julian Brave NoiseCat spoke of the Great Law of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy—a five-hundred-year-old constitution that has guided its people through settler colonialism, military invasion, pandemics, and the systematic government kidnapping and reeducation of children. “Cultures are really just manuals for how we're going to do all these things together as people. If the Haudenosaunee can maintain their Great Law against an apocalypse, against genocide, I do believe that culture, and the stories that we tell about ourselves, and the words that we use to tell these stories, are some of the most powerful things that we have.” As we sit in quarantine, it’s worth asking what COVID-19 says about our ways of inhabiting the planet—and how our stories might change in response. We wouldn’t be the first to do so: artists have long used plagues to amplify questions about what it means to be human.

In Albert Camus’s The Plague (1947), an Algerian city is walled off following the outbreak of plague. When the disease abates, the city celebrates, but the protagonist, a doctor, knows that the plague will eventually come back, because “everyone has it inside himself, this plague, because no one in the world, no one, is immune.” More than a simple disease, the plague is a reminder of the fragility of the human condition.

In Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826), a shepherd witnesses the progressive falling apart of human civilization due to plague. Cities, art, and society all disintegrate, leaving the shepherd to roam alone through an emptied landscape. Shelley’s is a pessimistic plague, insisting that humans are not the center of the universe, that pride comes before the fall.

In Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353) and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death” (1842), groups of nobles flee the cities—to a rural villa and a gothic abbey, respectively—to avoid disease and pass the time in celebration. Bocaccio’s youths use their quarantine as an opportunity to inspire and amuse each other with tales of humanity; Poe’s bored aristocrats come to a bloody end among the decadent trappings of their entertainment.

In Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), a group of educated young friends pursues an aristocratic vampire landlord through a complex network of cities, ships, trains, and properties. Stoker’s novel, and especially F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film adaptation Nosferatu, use vampirism and disease to speak of the fear of the Other—especially the Easterner—and of the spread of contagion through an increasingly globalized infrastructure.

Each of these stories imagines disease through specific spatial contexts. For Camus, walls keep the plague in; for Poe and Bocaccio, they hold it out. Shelley’s shepherd is left to wander the ruins of urban and rural life, whereas Stoker’s young professionals travel through a highly connected urban-rural landscape. These stories of disease are also stories of space, of how its management—through walls, public squares, roads, and countryside—enables life and death.

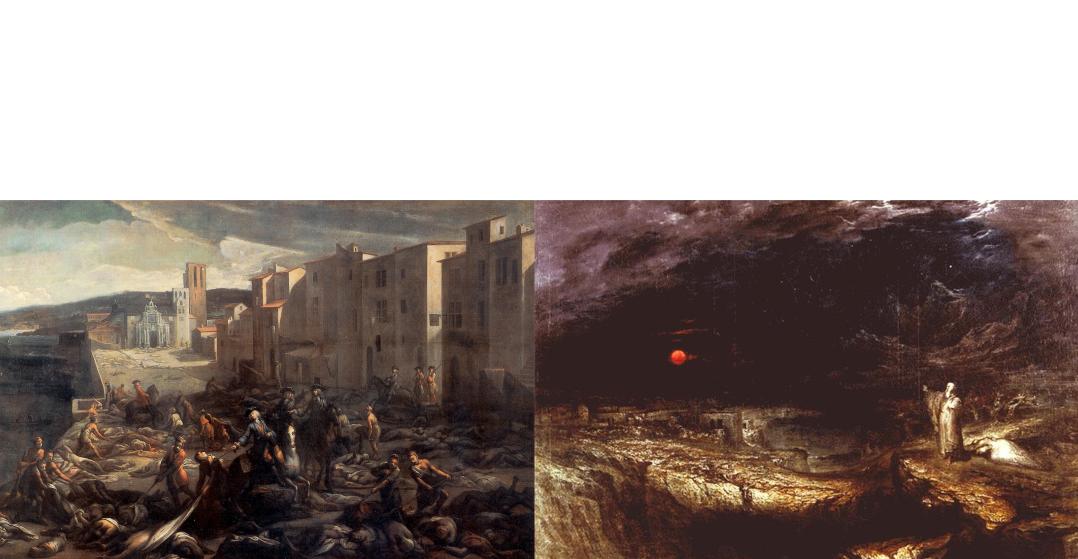

In 1721, the French painter Michel Serre depicted a scene from the Great Plague of Marseille. Dreary clouds loom over buildings that appear empty and lifeless. The city square, the heart of the public realm, is strewn with bodies, the distinction between living and dead blurred. At the center of this maelstrom, sitting calmly on a rearing horse, a city official directs the removal of corpses, a modicum of order in a portrait of devastation.

Left, Michel Serre, Scene of the Plague of 1720 at La Tourette, ca. 1721. Right, John Martin, The Last Man, 1849.

Spaces of Disease

Pandemics are not works of art. They are real, tragic events, occurring in the real, physical world. In “The Ecology of Disease,” the ecological writer Jim Robbins explains that epidemics “don’t just happen. They are a result of things people do to nature.” In other words, human socioeconomic systems interact with the environment to create conditions that harbor and produce disease. Our contemporary systems are characterized by neoliberal capitalism, intensive resource extraction, and unceasing encroachment on wildlife habitat. Potential disease vectors like mosquitoes, ticks, and bats are most prevalent at the urban periphery, where human activity penetrates biodiverse ecosystems. It on these peripheries that diseases are most likely to make the jump to humans. This, along with modern air travel, the intense growth of animal agriculture, and wildlife trafficking are all characters in our modern stories of pandemic.[1]

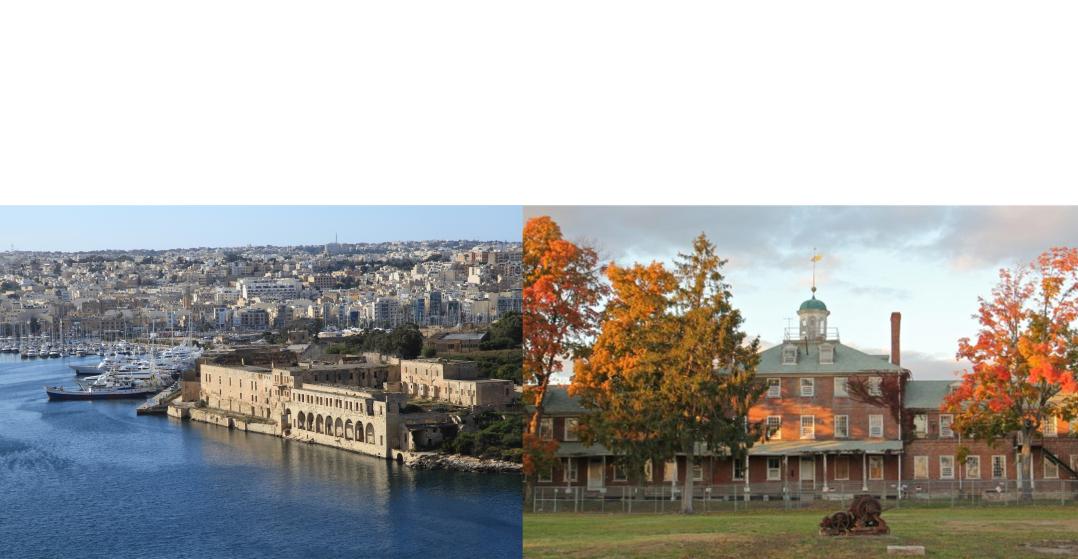

From the ancient past to the present day, the management of space—of people, animals, objects, and environment—has been the primary strategy for containing the spread of disease, even if the theories about how that spread happens have changed dramatically over time. In just a few years at the end of the 1340s, the Black Death, again caused by Yersinia pestis, killed at least a third of the European population, along with millions across Asia and Africa. Governments, especially of societies built around trade, responded by managing the movement of people and goods across borders. Ships suspected of harboring diseases were held in quarantine, their passengers stationed in specially constructed facilities known as lazarettos. The lazarettos of maritime nations were close to the water, often isolated on islands. Though not explicitly prisons, the lazarettos were nevertheless highly surveilled; they often served an additional role as hospitals for contagious diseases like leprosy. The Philadelphia Lazaretto, built in 1799, still stands on the Delaware River, surrounded by the sprawl of Philadelphia International Airport.

Lazarettos in Malta (left) and Philadelphia (right).

It’s easy to forget the extent to which our landscapes have been designed to mitigate disease. Nineteenth-century city planning in Europe and North America was built on notions of cleanliness. Frederick Law Olmsted was obsessed with the environment’s influence on the body, convinced that parks could benefit the health of weary urbanites by exposing them to fresh air and greenery. He also believed, paternalistically, that such spaces would inspire moral behavior among the poor, immigrants, and alcoholics, helping them integrate into the bourgeois public realm.

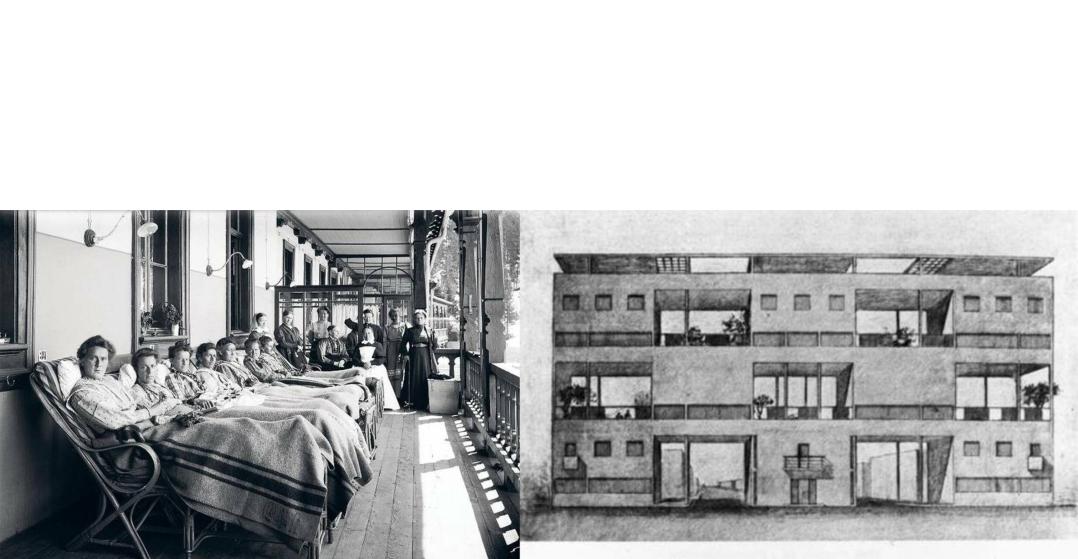

Theodore Roosevelt, the stalwart defender of natural conservation, himself suffered from debilitating asthma as a child and embraced an out-of-doors, physically active lifestyle as a response. In Roosevelt’s personal narrative, shaky health led him to an appreciation of “wild nature” as source of vigor—in turn informing his promotion of national parks. And Le Corbusier, the icon of modernist urbanism, lived through the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed perhaps three percent of the global population. His views on city planning were inspired by the architecture of Alpine sanitoria—resorts in places like Davos, Switzerland, where one could fight lung diseases like tuberculosis with the weapons of fresh mountain air, luminous balconies, and rest. Corbusier’s vision of the “tower in the park” evokes these efforts to optimize light, air, and space.[2]

Left, patients on an open-air porch at a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, 1910. Right, Le Corbusier's scheme for a housing development near Bordeaux, France.

Our contemporary stay-at-home orders follow in this long tradition of containing disease through environmental design and the control of space. As a landscape architect interested in how we manage and feel our way through space, I am captivated by how quickly our experiences of space have changed in the past few weeks. For over a month, I have barely ventured beyond a one-mile radius around my home in Berkeley. This limited range of observation is telling in itself: staying at home has hyper-localized my daytime routine.

My neighborhood is typical of Berkeley: houses separated by driveways, small gardens out front, little activity visible to the public. In the past two weeks I have met more of my neighbors than in the previous two years. Our conversations feel like breaths of fresh air, as previously separate social worlds meet for the first time. Our voices join a humble symphony of sounds previously muted by the noise of traffic: not just birds, HVAC whirs, and police sirens; but also the echo of footsteps on asphalt, a wooden door closing, the clicking gears of a passing bike. They’re all sounds I’ve heard a million times before; but they emerge with particular clarity when there is quiet, and time to pay attention. The internet is filled with news—some fake, some real—claiming that nature is reclaiming locked down urban spaces. Yet although there is clear evidence that some environmental stressors like air pollution are down (for the time being), many of these claims are simply expressions of renewed attention to what’s been around us all along. It appears we have forgotten that spring happens every year, that the moon waxes and wanes.

Meanwhile, I look at surfaces with unprecedented anxiety: that bench, this grocery bag, my phone, the mailbox—how long can the virus linger on them? I offer lemons that I have picked from a tree to a friend. She refuses them; I don’t blame her. The interconnectivity of human beings suddenly takes a dismal turn: human networks as disease networks. The instinct to love, to share, to touch, is challenged as we are forced to share our humanity in innovative ways. Online video sessions take on new significance as we realize our colleagues have living rooms, kitchens, partners, and lives of their own.

Blaise Pascal once quipped that “all of humanity's problems stem from Man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” As we sit at home, we are reminded that we live in a culture addicted to speed and a mythology of more-more-more. Even though there is no shortage in food supplies—at least not in rich neighborhoods—we raid the supermarket shelves to reassure ourselves that we can fill our existential void with something, anything. World leaders promise that the economic engine is only slowing down, not shutting down. At Whole Foods, the music buzzing out of the loudspeakers says the same thing: don’t worry, be happy. Everything is OK.

But, no, everything is not OK, not when employment is tied to carbon-intensive supply chains, not when slowing down means going hungry, not when a functioning economy means threatening life on Earth. Despite the omnipresent government rhetoric of war against the virus, we need to be crystal clear about something: COVID-19 is not the true enemy; the real struggle is against its underlying conditions of environmental destruction and social inequality. I say this keeping in mind those most impacted by the virus—the sick, the poor, the elderly, people of color, healthcare workers, the unemployed. The suffering and fear are inarguably real. Yet the pandemic is the symptom of a much larger crisis of how we inhabit the planet. I won’t dwell on the relationships between the coronavirus and the climate crisis—many others are exploring these questions.[3] All I will say is that a return to normal cannot be our goal.

It’s tricky writing about a crisis in the midst of it—something like painting an earthquake in real time. Yet if pandemics teach us anything, it is that they touch the core of our humanity, and yet we still manage to forget them when times are good. Today, our fragility, our love, and our folly are as clear as the unpolluted skies. But tomorrow they may fade away into the haze of business as usual.

No one knows what the legacy of COVID-19 will be. In quarantine, our perception of space is seeded with a growing awareness that we are connected not just physically—through infrastructure, public space, and microbes—but also through our needs, which we are discovering to be much, much less than we are accustomed to. Whenever we begin to slowly emerge from our homes, these newly recognized essentials must serve as the building blocks of our designed environments. Perhaps sunlight is the greatest work of public art; perhaps looking our neighbors in the eye is the missing ingredient in our desire to build smarter cities. Perhaps letting go is as powerful as grasping for more.

Marseille still celebrates an annual mass to honor a three-century-old promise; the plague wall is now a place for bucolic strolls. Where will COVID-19 leave its traces? No one knows, but one thing is certain: it will be expressed in the stories and the spaces we share. Now is the time to mourn and to dream; to quietly listen and to fine-tune our attention to the possibilities at hand.

[1] Roger Keil, Creighton Connolly, and S. Harris Ali, “Outbreaks like coronavirus start in and spread from the edges of cities,” The Conversation, February 17, 2020.

[3] See Megan Crist's article on the subject, among many others.