Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

A Society of Professional Mourners

On the occasion of being invited to speak at a student panel during the McHarg Center’s “Design With Nature Now” conference, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Ian McHarg’s formative book, I came to reflect on what “designing with nature” means to someone like me, and like many of my peers, for whom nature has only ever been a source of sadness.

When designers speak about ecological crisis, it is not strange to hear such mythic words as “apocalypse,” “dystopia,” and “doom.” In some cases these words are used in earnest, as warnings or calls to action; in other cases they are ironic, used to delegitimize pessimistic voices as “doomsayers” or pessimistic imagery as “dystopian cliché.”1 In both discourses, these doom-words are only metaphors; I think it is worth briefly taking the apocalypse at face value.

In December, 1999, in Jerusalem, an Old Testament scholar named Albert I. Baumgarten composed the introduction to a collection of essays from across the sub-sub-discipline of religious studies concerned with the history of the end of the world. This scholar described how the typical apocalyptic movement undergoes a characteristic life cycle, with four distinct stages of development—in the fashion of butterflies and certain types of molds.2

The first stage in this Standard Model of Apocalypse is called “Arousal.” There are doomsayers in every age; their role is to be ignored and ridiculed by every passerby. But in certain moments, for some reason, the prophets manage to find, and keep, an audience. This is not more likely specifically in times of suffering, as we might expect—but rather in times of great change, for good or for bad. Perhaps when the rhythms of one’s life have been thrown into disarray it can be pacifying to think that it is in fact the cosmos which is in chaos.

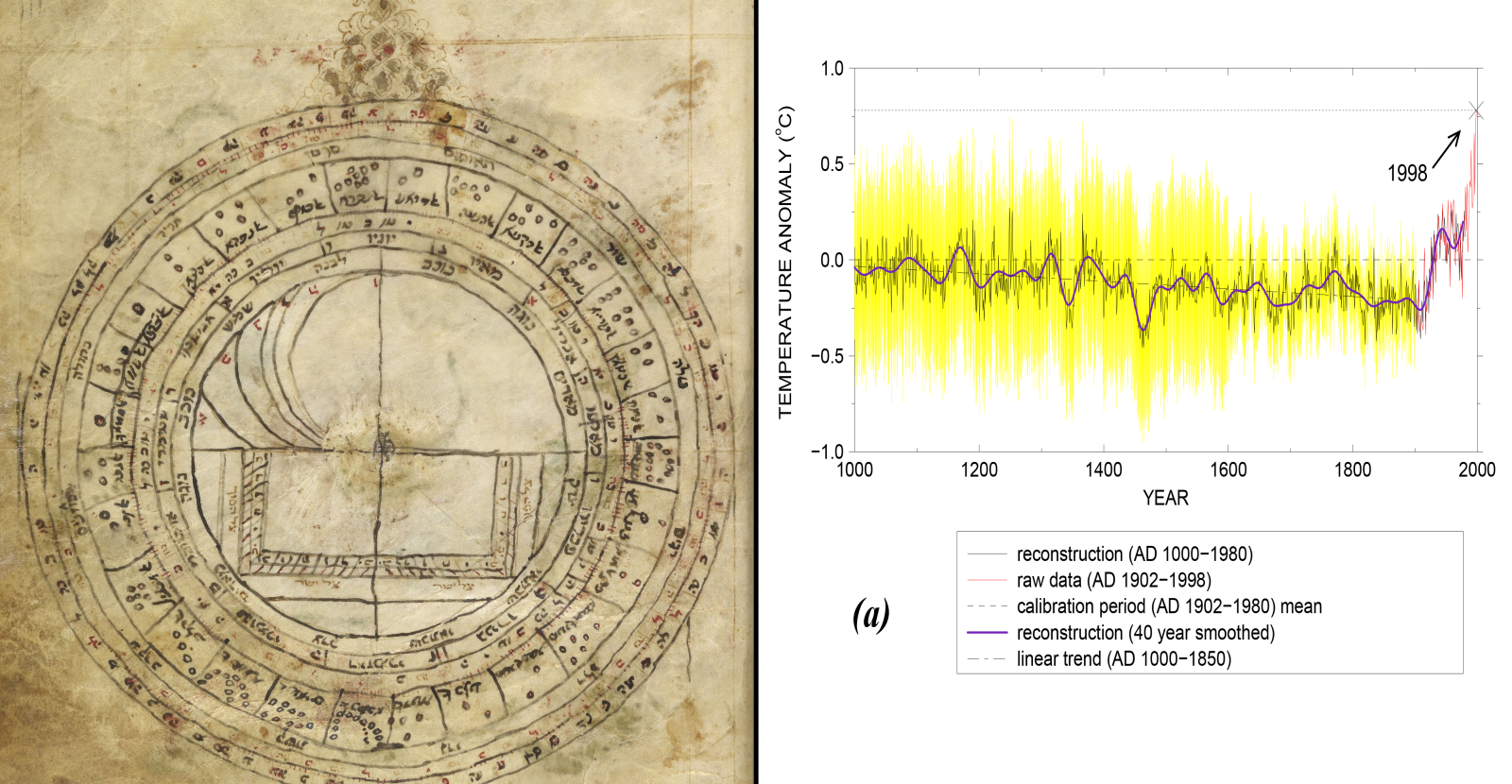

The second stage of apocalypse is called the “search for Signs.” It is a desperate, urgent search, characterized by what we might call intense interdisciplinary collaboration. Data points are found in the stars, in scripture, in disasters, in the strange behavior of animals, in ominous phenomena, and in arcane calculations—all to build the case for why the apocalypse will be real this time. Because, as our old apocalyptarian points out, believers are all too aware that their prophet is not the first; that many have predicted doomsday before them, and all have been wrong.

The third stage of apocalypse is called “Upping the Ante.” By burning their ships and ruling out the retreat to normal life, movements build solidarity through mutual escalation and counteract the tendency for schism.

And the final stage of the Standard Model of Apocalypse is called “Disconfirmation and its Aftermath.” The presence of “disconfirmation” in this framework reveals a bias present in apocalypse studies: a privileging of those apocalypses that don’t happen. But nothing here, I think, disqualifies real apocalypses from being considered through the same lens—and so this stage might be generalized to just “Aftermath.”

The aftermath stage rarely marks the end of the movement—even when the predicted doomsday comes and goes. Instead, believers are left to the confusing task of interpreting what, exactly, has just happened. Sometimes scapegoats are found—half-believers who ruined it for everyone else. Sometimes a miscalculation is discovered, and doomsday is simply postponed. But sometimes analysis of the evidence reveals that the apocalypse has, in fact, taken place—it was just hard to tell. What follows is a struggle for meaning, and a struggle over how to proceed with the knowledge that something fundamental in the world has changed.

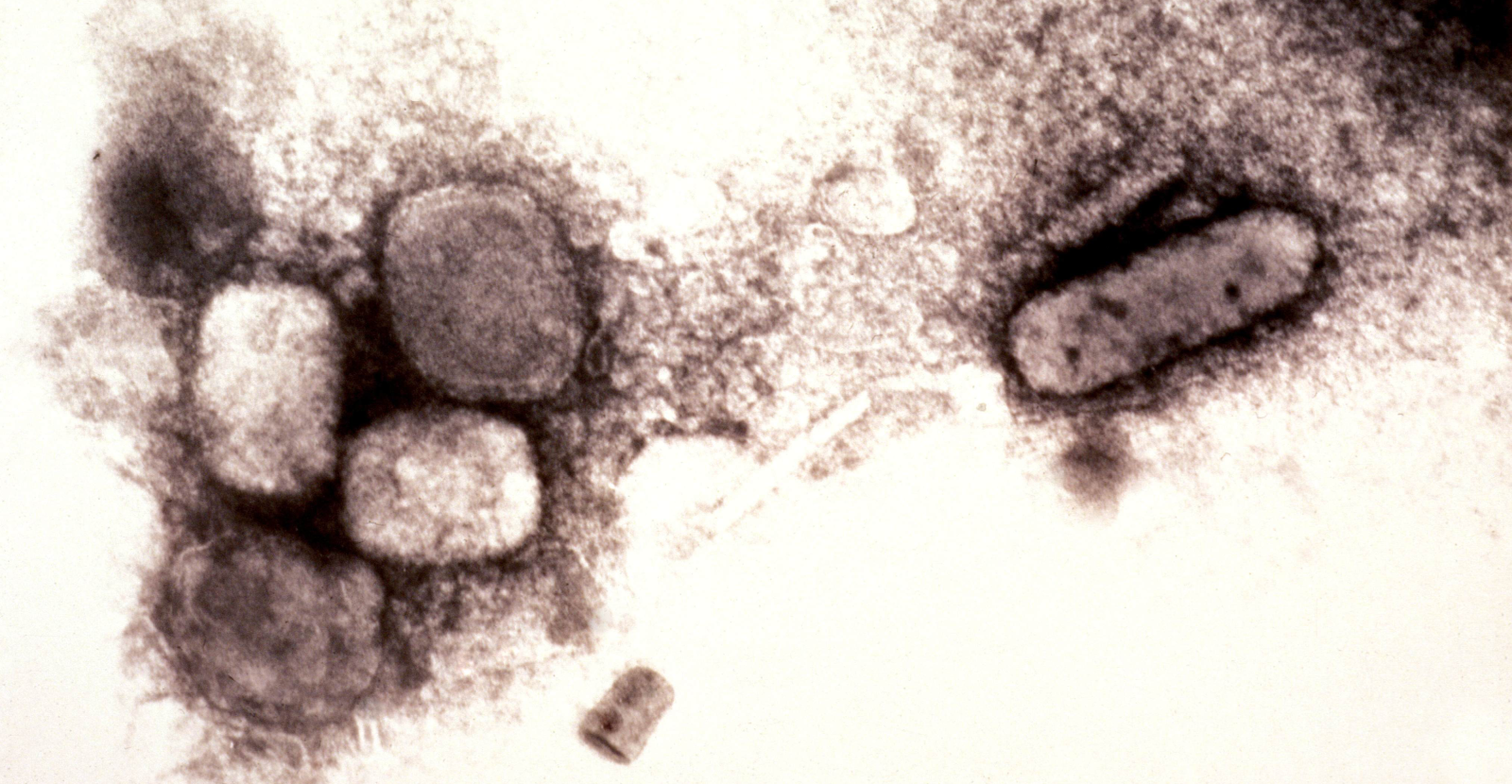

So how does our current apocalypse fit into this framework? It seems hard to tell. The Anthropocene transition has undoubtedly caused, or may soon cause, extinction for many: baiji dolphins, cryolite, smallpox, the Ben Ali regime in Tunisia, the glaciers in Glacier National Park, the European Union, the Temple of Bel at Palmyra, Tuvalu, hundreds of frog species, and countless others.

With these extinctions will also depart many of the joys, comforts, and luxuries that we have come to appreciate and expect in our age—despite what the most techno-optimistic among us might promise in the way of solutions. But we’re probably not, really, going to go extinct either—irrespective of beguiling deathbed narratives of post-human worlds, as presented in sci-fi, Paola Antonelli’s palliative Milan Triennale, or “world-without-us” visions of irradiated wildlife refuges and coral reefs in drowned cities.

No, dreaming about our own extinction feels like just as much of a cop-out as believing that everything is going to be fine. The truth is that we will continue to exist in a tarnished world, surrounded by reminders that things used to be better.

The apocalyptic tradition that best fits our future is not an Abrahamic narrative of revelation and final judgment; but rather a Mahayana Buddhist construct called 末法—Mò Fǎ in Chinese and Mappō in Japanese. 末法 translates to “the end of the law” or, more interpretively, “the age of degeneracy.”

It signifies an inevitable, irreversible shift to a world in which enlightenment is no longer possible; in which Buddha’s teachings still exist, but in which nobody will be able to follow them. A thousand years ago theologians believed that this degenerate period was either imminent or had in fact already begun.3

This version of apocalypse does not mean an end to the world; but rather a void of meaning where the Dharma once was. 末法 is a better model for the ecological crisis than Christian apocalypses because there is no rapture; we’re still here, stuck in the “aftermath” stage, forever—but with the knowledge that something fundamental in the world has changed. This is an epistemological apocalypse—an extinction of meaning.

In her popular memoir H is for Hawk, the British naturalist Helen Macdonald writes the following:

“I think of what wild animals are in our imaginations. And how they are disappearing — not just from the wild, but from people’s everyday lives, replaced by images of themselves in print and on screen. The rarer they get, the fewer meanings animals can have. Eventually rarity is all they are made of. The condor is an icon of extinction. There’s little else to it now but being the last of its kind. And in this lies the diminution of the world. How can you love something, how can you fight to protect it, if all it means is loss?”4

H is for Hawk is a book about melancholy—the depression and self-hatred caused by a short-circuited mourning process, as schematized by Sigmund Freud in his 1917 essay “Mourning and Melancholia.”5 For Freud, melancholia takes root when the mourner is unable to fully abandon the lost love object—when the unconscious is unwilling to admit that what’s dead is dead. This unconscious resistance is most likely to occur when the lost love object has been the object of intense ambivalence—when the love relationship is really a love-hate relationship. Unwilling to acknowledge this latent hatred, the melancholic lapses into a fugue state of self-loathing, depression, and performative sadness.

I’m not going out on a limb to suggest that humans feel a fundamental ambivalence toward “nature”—as something to be tenderly stewarded and bloodily extirpated, to be sorrowfully lamented and lustily raised for slaughter. What if, because of this ambivalence, human society (and, paradoxically, especially those of us most concerned with the idea of “nature”) can’t admit that the end of the world has already happened? Because it has gone unacknowledged, the epistemological apocalypse is causing a crippling ecological melancholy, ensuring that humanity continues to spin its wheels, stuck halfway between Holocene and Anthropocene.

The evidence for this melancholy is all around us; landscape architects in particular don’t have to look far. One of the lessons we’ve learned from sci-fi and its study is that we should look to the background of the artwork to see the speculative project in action. And ecological melancholy runs all through the imagery that landscape architects use to fill in the background of their renderings.

In school we are generally not taught to populate our drawings with mourners, tombstones, crashing planes, and mushroom clouds—with so-called dystopian clichés. We prefer gleeful kayakers and twittering songbirds; in the worlds of our design, the golden light of the Holocene is everywhere and overwhelming.

But a closer look reveals that many of these stock characters seem to be experiencing profound distraction, alienation, and denial. This melancholy may be unconscious and repressed for now. But what happens when the meaning of a songbird changes: from representing joy, and freedom, and love, and beauty, and biodiversity, and happiness, and responsible stewardship—to being only, in Helen Macdonald’s words, an icon of extinction? What do we draw?

I will conclude by first saying that I don’t consider myself to be hopeless (for what it’s worth), and I am not arguing that we should give up trying to improve our world. Rather, these frameworks of doom promise enormous creativity, and hint at new roles for designers—grounded in the need to recharge the world with meaning. Our old apocalyptarian wrote that “the consequences of a successful bet on the millennium can be far reaching. . . . Assured that millennial time is in effect, all possibilities seem realistic.”6

As 末法 dawned, bringing society crumbling down with it, scholars and artists developed novel forms of art and poetry tailored to their new, tarnished world; the Byōdō-in, now a preeminent national icon of spiritual architecture, was built in 1052 by a designer who believed that 1052 was the year in which meaning vanished from the world—and that this was the answer.7 Even Freud believed that melancholics see themselves—and the world—with a uniquely un-mediated clarity, focused by their own self-loathing.

Two short quotes have proven to be particularly helpful in this reflection on the end of the world.

The first is by Anne Spirn, who wrote, at the turn of the millennium, that landscape architects since Ian McHarg have tended, to their detriment, to “borrow methods and theories from disparate disciplines rather than generating them from within the core knowledge and actions of landscape architects.”8

The second quote is from a glamorous Nature profile of a technology entrepreneur named Alex Deghan, titled “Hacking conservation: how a tech start-up aims to save biodiversity.” Deghan remarked that the problem with conservation is that it is “filled with conservationists,” and that “the Society for Conservation Biology is a society of professional mourners who lament and describe the passing of species.”9

This is a joke and a provocation—but I can’t help but take him at face value. Like conservationists, landscape architects are doing a great many different kinds of things to make the world a better place. I would never ask them to stop. But how many of these activities are specific to landscape architecture—are not “borrowed” from “disparate disciplines”? Put simply, do we have any knowledge of our own?

Perhaps the “core knowledge and action” of landscape architecture is this: to recharge the landscape with the meaning it has lost in the epistemological mass extinction, allowing humans to finally come to understand our crippling ecological melancholia and move past our Holocene hangups. I won’t go so far as to say that the American Society of Landscape Architects should immediately rebrand itself as a society of professional mourners. There are still too many different roles we need to play. But if the world does need mourners, it is surely landscape architects who have the knowledge to mourn it the best.