Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

Renewing Renewable Power in Lowell, Massachusetts

Lessons for decarbonizing small cities

While more and more governments and communities are pledging to reduce their carbon footprints, their resolutions often lack a clear framework for achieving their laudable goals. How can a city, particularly one with fewer resources, turn a commitment to achieving 100% renewable energy in the future into an actionable plan? Here, we examine what one roadmap might look like for the City of Lowell, Massachusetts, which has pledged to transition to 100% clean, renewable energy in the city by 2035.[1]

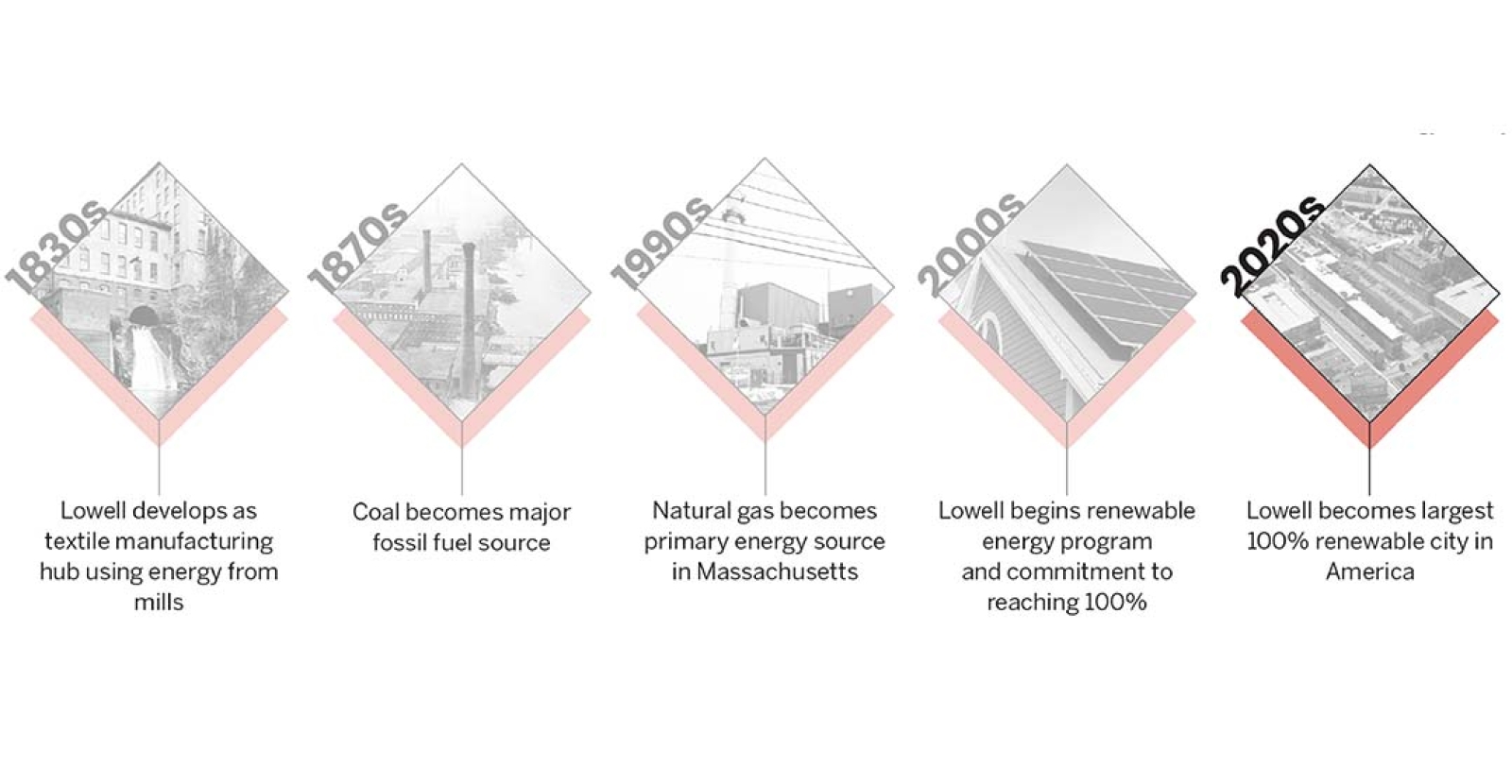

Lowell is a mid-sized city in Northern Massachusetts hoping to build on its history of innovation in production and energy: the city is often referred to as the birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution due to its founding as a planned textile manufacturing center using mill power in the 19th century.[2]

The city can continue to expand on its rich history of worker organizing that can be built on by ensuring liveable wages and benefits for those who do the work of overhauling the city’s energy system.[3]

Alongside a larger revitalization effort of the city center, Lowell’s City Council adopted a resolution in 2017 supporting the 2035 clean energy target. The city can hardly match its ambition without a detailed plan. Though more than 150 American cities have now pledged to eliminate carbon emissions by some future date, only a few are on track to achieve their goal. Out of the handful of cities which have met their target of operating purely on renewable energy, fewer still have achieved it without utilizing legal loopholes, caveats, or vague language.

Lowell immediately stands out as an unusual place beyond its historic renown. This site of major labor struggles and historic progress in renewable energy features many large, flat roofs, and high energy usage during cold New England winters, making transitioning to renewable energy seems a heavy but plausible and necessary lift.

The extent of the city's concrete planning efforts to decarbonize has not kept up with their stated goals, with budgetary and programmatic constraints resulting in a ‘two steps forward, one step back’ approach. A state program made it possible for Lowell to hire an energy manager to begin gathering data on energy uses and efficiency, a solid place to start, but the effectiveness of this position was undercut when the city recently and unexplainably ended a Community Choice Aggregation (CCA) contract which would have provided the city with energy from 100% renewable. This backward motion shows the importance of going beyond simply trading fossil fuels for renewables elsewhere through a CCA. The City’s roadmap would therefore have to get as close as possible to a self-sufficient 100% plan. This would move the collective ball forward instead of only adding to demand for remote renewables through a CCA, which heavily relies on buying renewable energy from other parts of the region to help meet their renewable energy state mandates and local goals.

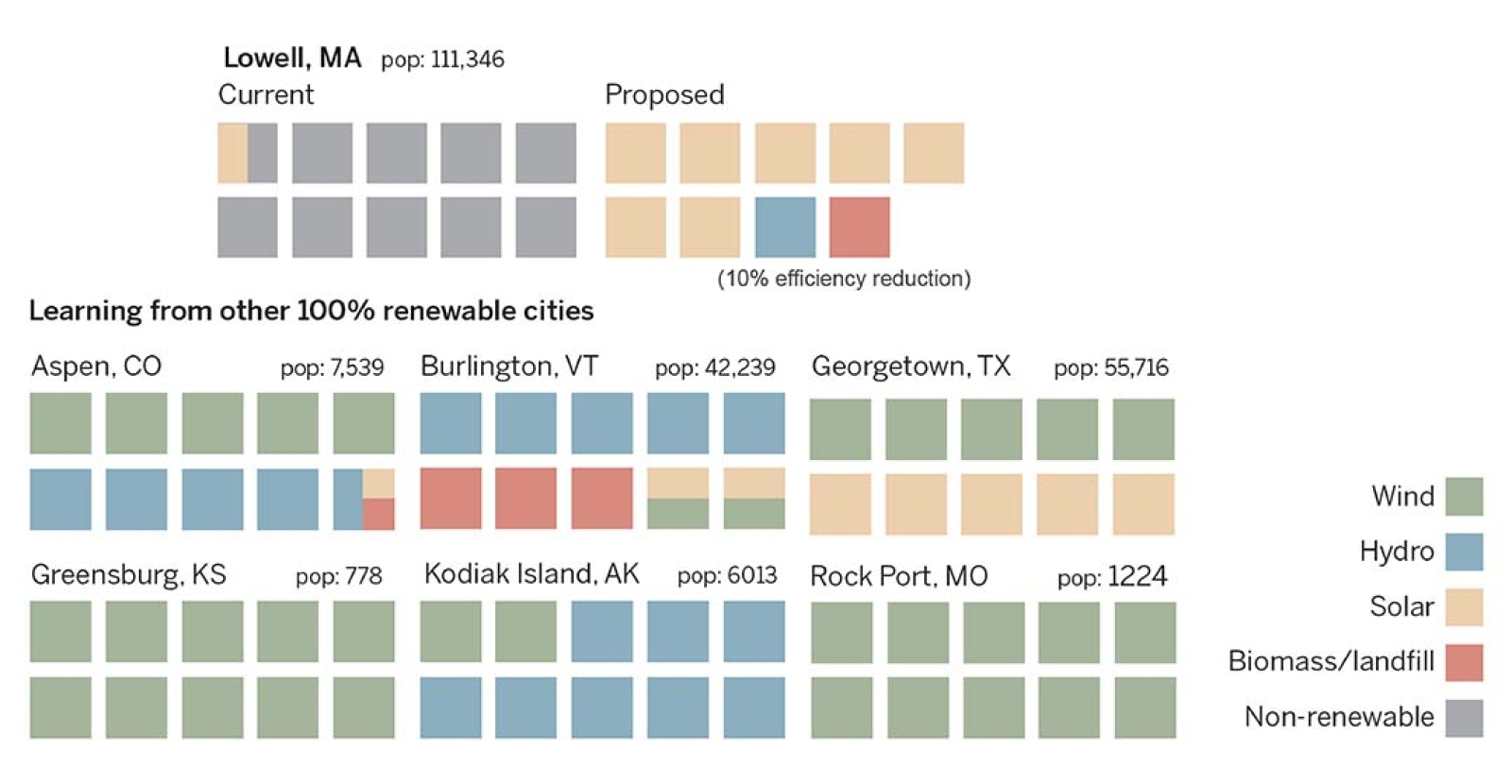

Success stories elsewhere offer useful guidance. Of the six small cities considered to have achieved 100% renewable energy at that time of this research (Spring 2019), Burlington, Vermont (thank you Bernie) and Aspen, Colorado were the best precedents due to a mix of renewable energy sources, instead of tapping into a singular massive wind or solar source, such as those powering towns in Texas and Kansas. In all cases, energy storage is an ongoing challenge, but that is hardly a reason not to proceed.

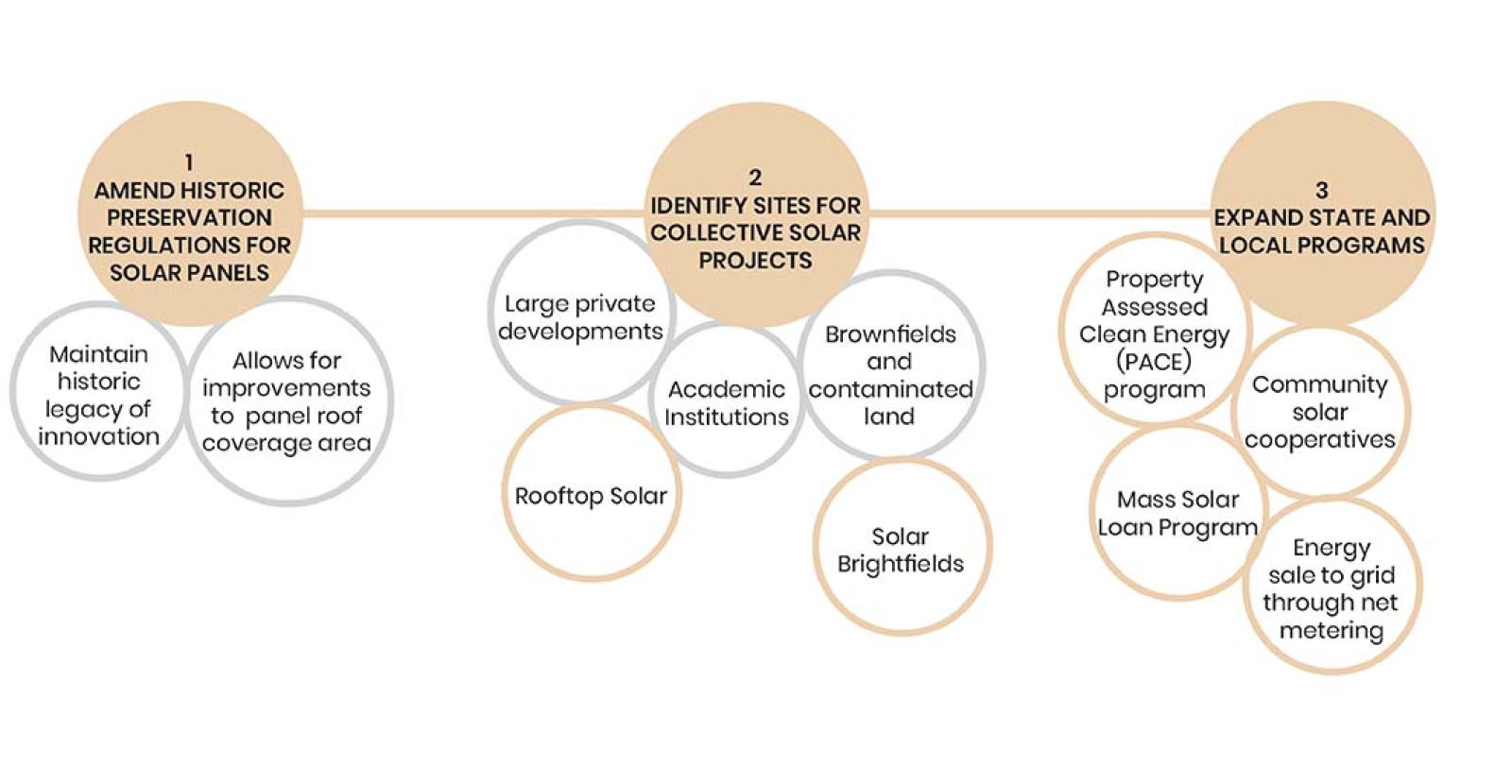

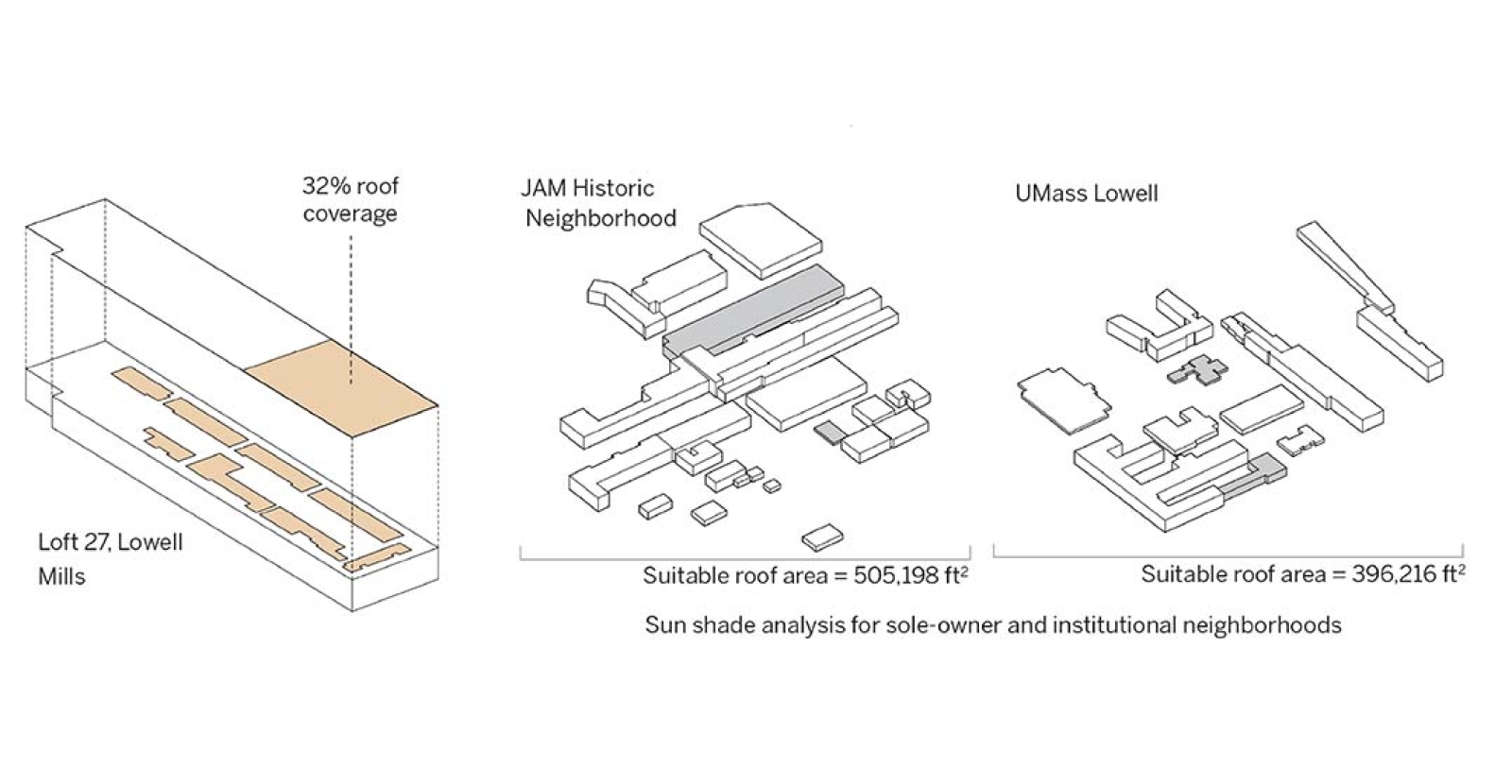

While wind farms are effective elsewhere, even small-scale wind power was not an option for Lowell. The wind turbine capacity maps suggest that even drying clothes on a line would be a challenge within the city. Solar power, on the other hand, offers a huge amount of promise in Lowell (a city at a lower latitude than Germany, which gets more sunlight than one might think). Indeed, immense flat roofs, a relic of the city’s former industrial mills, are a promising site for high-volume, public power generation. Careful analysis of rooftop sizes and shadows informed the model for powering the city in part with mill-top solar. Poring over downtown on Google Earth reveals a patchwork of solar projects that look like hopscotch courts or a forgotten game of Tetris. Lowell’s historic preservation regulations prohibit solar projects from being visible from the ground, thereby dramatically reducing their allowable roof coverage, energy generation potential, and in turn, economic viability.

Changing historic restrictions are a key first step for dramatically expanding the city’s solar energy output, which could potentially supply up to 70% of the current energy use through widespread adoption on public and commercial buildings and an aggressive residential program. Moreover, changing these restrictions would better honor the history of Lowell. Founded on hydropower, the Lowell mills are an early and important case study in the country’s renewable energy story. What better way to honor the city’s roots than by leading in this area once again, this time propelled by the unparalleled urgency of the climate crisis?

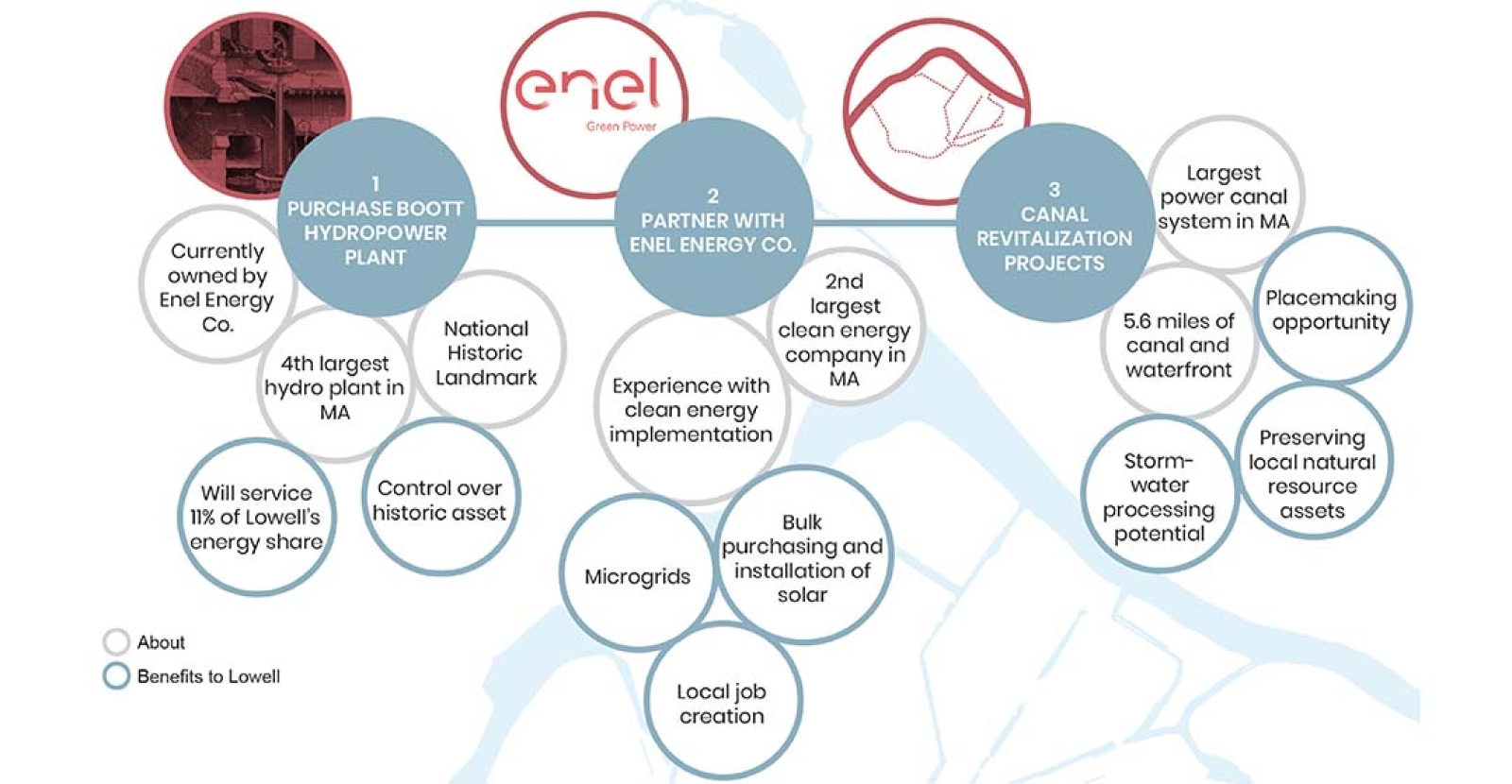

Hydropower offers an even more compelling opportunity to decarbonize a city that was strategically planned around canals. This power canal system still runs through Lowell, and the the fourth largest hydropower plant in the state has successfully tapped into this resource, further defining the geography of downtown. Unfortunately, the hydropower plant is now in private hands, and it is difficult to know where that energy goes, as it seems to be sold to the highest (often non-local) bidder. This is doubly unfortunate because the company that operates the canal system also owns the banks of the canals themselves - a move that has privatized previously public waterside urban spaces. This made the path forward even more clear: the City of Lowell should take on public ownership of the canal’s power as a requisite central and symbolic step in reestablishing their independence and leadership, ensuring that renewable power is allocated through algorithms based on proximity instead of profit.

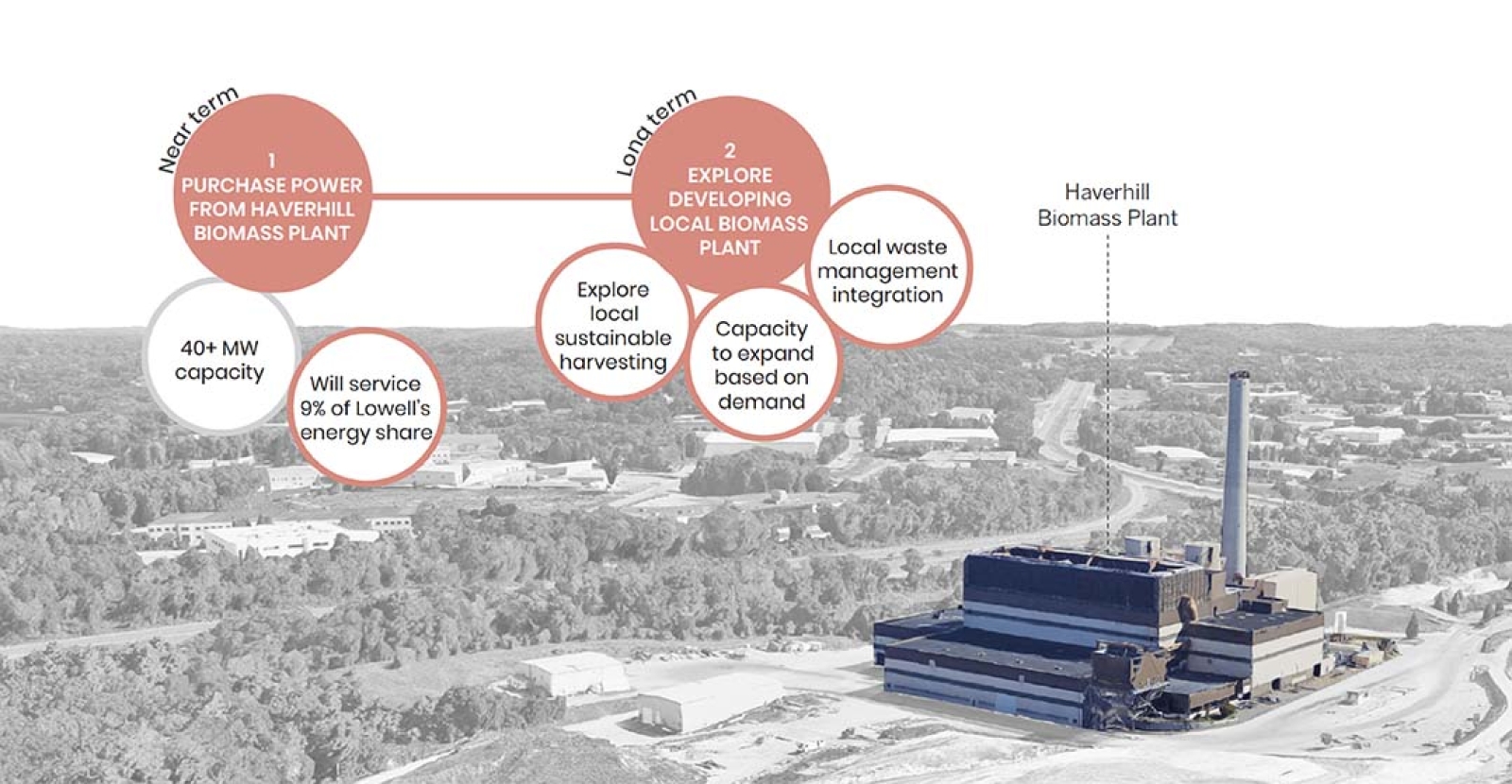

Even with aggressive plans for solar and hydro power in place, meeting Lowell’s energy needs through renewable sources remains a challenge. Already decarbonized cities like Burlington have filled in similar gaps employing biomass energy generated by burning wood chips. Fortunately for Lowell, there is already an operational biomass plant in the nearby City of Haverhill. To meet its energy needs, the City of Lowell should purchase this plant, which would deliver a substantial 9% of Lowell’s energy share. Much like the proposed acquisition of the hydropower plant, this would also give Lowell greater autonomy in managing its energy sources and create opportunities for the city to integrate its waste management processes into its renewable energy goals.

These strategies can be complemented with an extensive energy efficiency push as the bridge to help Lowell to meet its goal of transitioning to renewable energy. It’s inspiring to think that this city, which had once been a regional powerhouse in energy production and job creation, once again has the opportunity to become a leader in renewable energy generation -- in doing so, it would become the largest American city to make good on this promise. However, Lowell is also faced with the potential for climate gentrification as a result of these advances.

The immense development and investment that will arise from a 100% renewable plan will be beneficial to the city, but it also risks displacing the most vulnerable populations as property values rise. As concurrent steps, it is necessary to incorporate aggressive policy to stabilize and secure housing and high road labor strategies to service the people living in the city today. A central opportunity of this path to 100% renewable energy generation is job creation, which can be emphasized by expanding partnerships with local institutions. One such partnership currently exists with UMass Lowell, who have conducted leading economic research and estimates on renewable job creation. Already available programs, such as the Graduate Certificate in Renewable Energy Engineering, directly create opportunities for residents through apprenticeships and paths to local employment. These are integral to a successful energy transition strategy and should be implemented in tandem with expanding renewable sources.

This project presented us with a unique opportunity to concretize steps toward carbon neutrality based on policy goals. However, working on energy strategies can often seem like it’s outside the scope of a planner’s work. Unsurprisingly, an architecture professor at our final presentation questioned our scope of this project, saying that it was outside the domain of the urban planning profession. For us, this demonstrated that the task of ensuring our planet’s future must be cross-disciplinary. If urban planning is to play a leading, or even relevant role, planners must lean into the political struggles implicated by any plan for the built environment. If we want to address the climate crisis, we must leverage the essential role of a planner as an intermediary between different public departments and work across professional silos. Energy generation and infrastructural decisions play a fundamental role in shaping the built environment, even if they often take a back seat in planning pedagogy. Now, having graduated from the urban planning program, we have a responsibility to move our profession towards thinking about climate as an urgent collective endeavor, rather than an afterthought in a planning application.

[1]https://www.sierraclub.org/sites/

www.sierraclub.org/files/sce-authors/u11612/

Lowell%20100%25%20Resolution.pdf

[2] https://books.google.com/books?id=ELqCBAAAQBAJ

[3] The History of America in Ten Strikes - Erik Loomis

Amaya Bravo-France is a Housing Affordability Associate at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, working to ensure equitable access and generate sustainable solutions to the housing crisis in California. Amaya completed a Master's in Urban Planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 2020, where she focused on both housing and environmental issues, and previously studied environmental science at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Saul Levin writes and organizes climate justice policy. He is Senior Climate Advisor to Congresswoman Deb Haaland (NM-01) and a Fellow at Data for Progress. He has organized with ORCA, the Sunrise Movement, and the Climate Disobedience Center, and studied Environmental Studies at UChicago and Urban Planning at Harvard.

Safeer is a recent graduate of the Master in Urban Planning program at Harvard Graduate School of Design. During his time there, he focused on urban analytics, resilience and transportation, and hopes to use his skills to represent marginalized communities at the local scale. Prior to that, he practiced as an urban designer in the UK, where he worked on comprehensive masterplans and community outreach for public sector clients.