Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

Persisting Dynamics: A Tale of Displacement

1<WORLD<2

Indigenous communities in India from a broader perspective are currently undergoing a shift in their way of living and abandoning their cultural practices for a variety of reasons. This is consequently resulting in the loss of age-old practices and ancient wisdom deeply rooted and closely related to their place of living, having evolved a way of life alongside the natural cycles and processes of their surrounding environment. There has always been a nature-culture interface and correlations between the two form the datum for settlements to flourish. The research attempts to investigate one such correlation between the pastorals and the depleting grasslands of a predominantly mud flat region along a Ramsar wetland in Gujarat, India: Nal-Sarovar.

Nal Sarovar, a land-water binary system, is the result of the choreography of water. Pastoral peoples here have been surviving on the vast expanses of land along a fragmented tributary of river Indus for generations. Continuous dynamics are visible through the mobility of water and thus the dependent cultures that gathered, settled, survived, and progressed on the shores of this wetland system. Several narratives, myths, beliefs, and facts play a background role behind the “tales of displacement” communities face that eventually with the flow of time reached Nal Sarovar. These displaced communities have subsequently paved the way to the formations of the cultural landscapes of this region. Though the antecedent generations flourished here and people are currently surviving in the present, it is anticipated that there will be a shift in these deep-rooted beliefs spurred by modernization causing changes in the aspirations of younger generations in this region. Recently, human interventions and the climate crisis have led to the ecological deterioration of this region, hampering the complex landscapes and leading to alterations in the cultural practices of those inhabiting them. The research thus investigates the shifts in livelihood practices and tries to identify newer landscape rituals which are based on the principle of ecological restoration. It envisions strategies for resilience within the existing landscape that act as catalysts in upgrading livelihoods of the pastorals, conserving their way of life and strengthening their associations to systems of this wetland. The research methodology is in four stages: Traces, Threads, Knots and Weaves. Traces unfolds the micro-readings of existing systems, i.e forms of waters present in the wetland system from geologic timelines to present. Threads evolves through investigating unseen links of nature-culture interfaces and the present responses of pastorals with the wetland. Knots focuses on the current disruptions and loss of cultural practices. The three stages culminate into a Weave, bring the pieces together to think about the systems future.

One Sea, many waters - Understanding systems within the system.

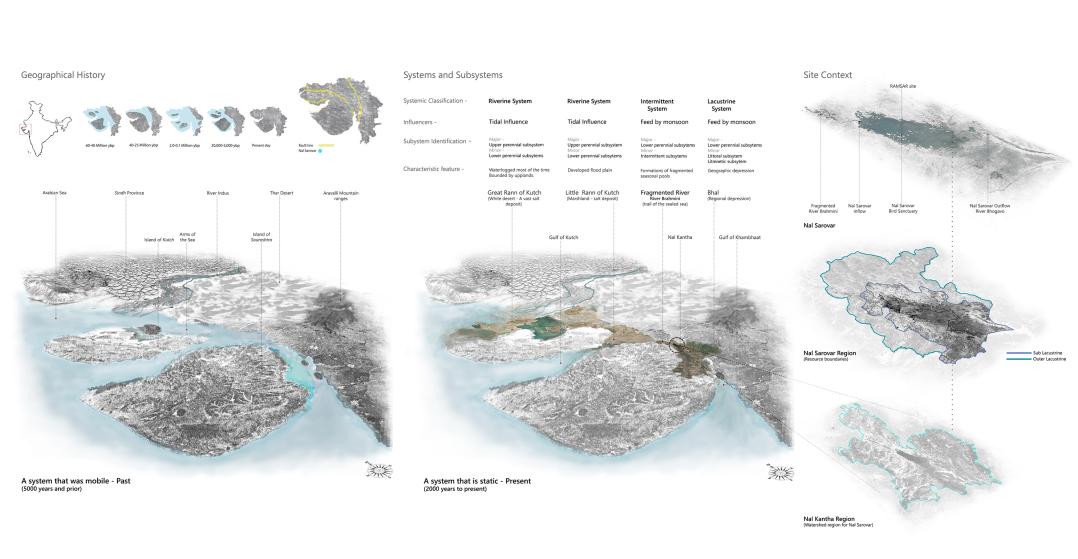

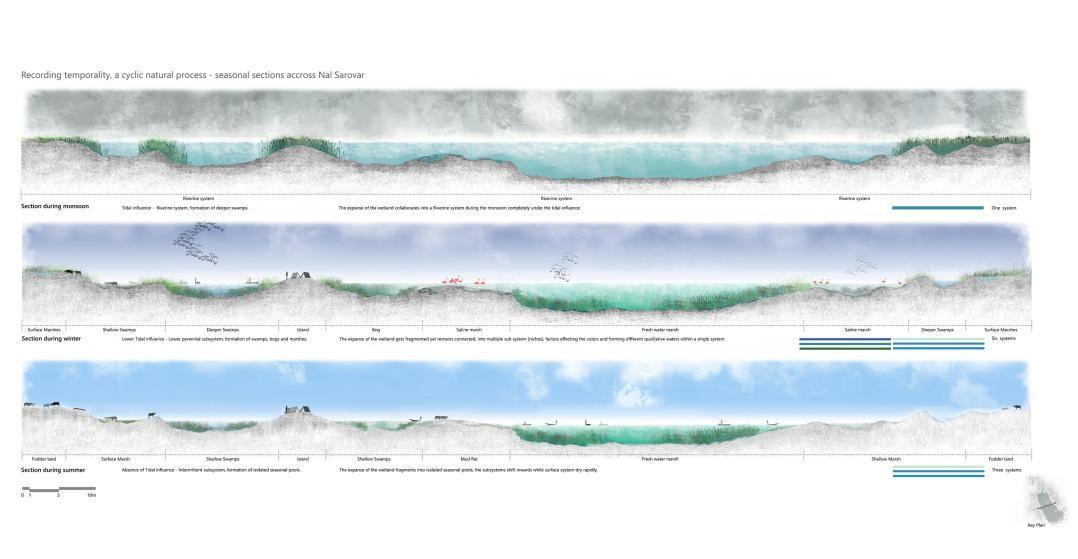

The systems of water have shown an invigorated nature since the beginning of time and have predominantly been unobtrusive, which is, perhaps, the primary reason for the association man developed with water. We see the trails of human history along water bodies, be it oceans, rivers, lakes, ponds, or a simple well; the placement of this fundamental element has always had a centre seat in the evolution of mankind. Presently, Nal Sarovar manifests its origin back into the era of tectonic events taking place several million years ago, thus the combined effects of geographical history and water have characterized the Nal Sarovar region as a complex and layered land-water binary which has subsequently evolved into a wetland. Nal Sarovar is evidently seen to have been derived from the waters once called the arms of the sea, a shallow connection of the Arabian sea between the gulf of Kutch and gulf of Khambhat, separating the mainland from the islands of Saurashtra and Kutch. A mythical river is said to have flowed through the Thar deserts and entered the present Great Rann of Kutch, further moving into the present Little Rann of Kutch and emptied itself into the gulf of Khambhat. Nal Sarovar sitting on this very route of complex water systems obtained its characteristics that flowed along with “the many waters”. As many waters came from a larger flowing source, “the sea”, they carried sediments, vegetation, marine life, and many more similar aspects to create smaller systems nestled within the overall system. This wetland shows characteristics of a sea as well as that of a river. Over a million years the two islands shifted towards the main land and sediments sealed the shallow connection forming the fault-line. The different waters coming from a singular source collectively form Nal Sarovar. The classification of the wetland system thus ranges from riverine system to lacustrine sub-systems. The wetland is bounded by inflow and outflow rivers on both ends and undergoes major seasonal processes based on temporalities.

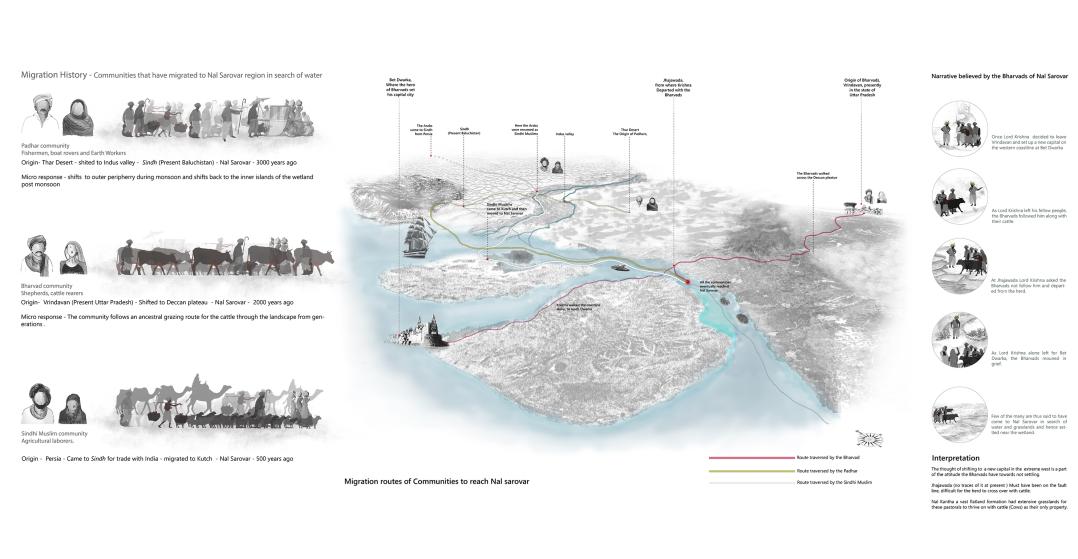

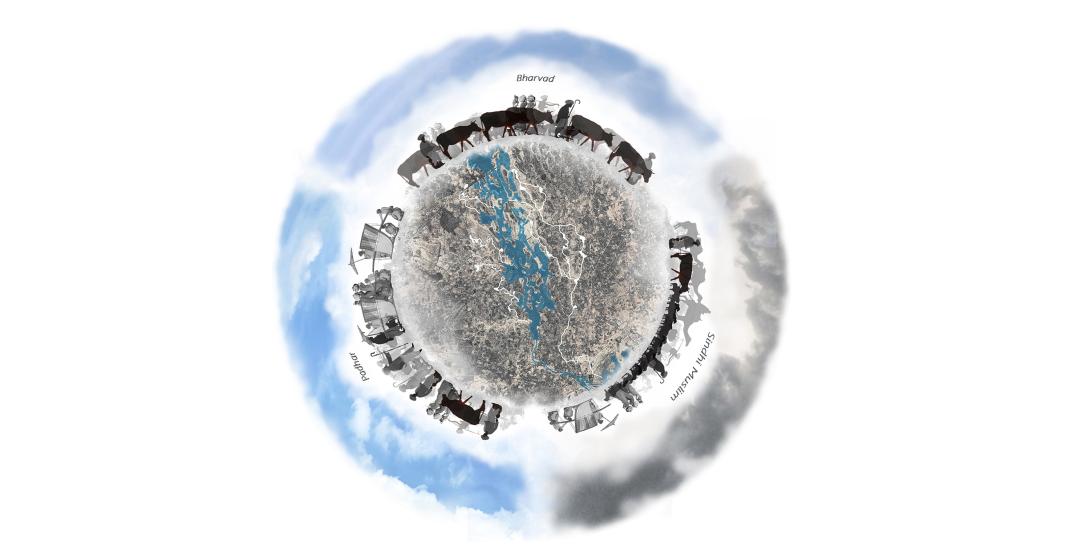

Many waters, one system - Understanding mobility with water

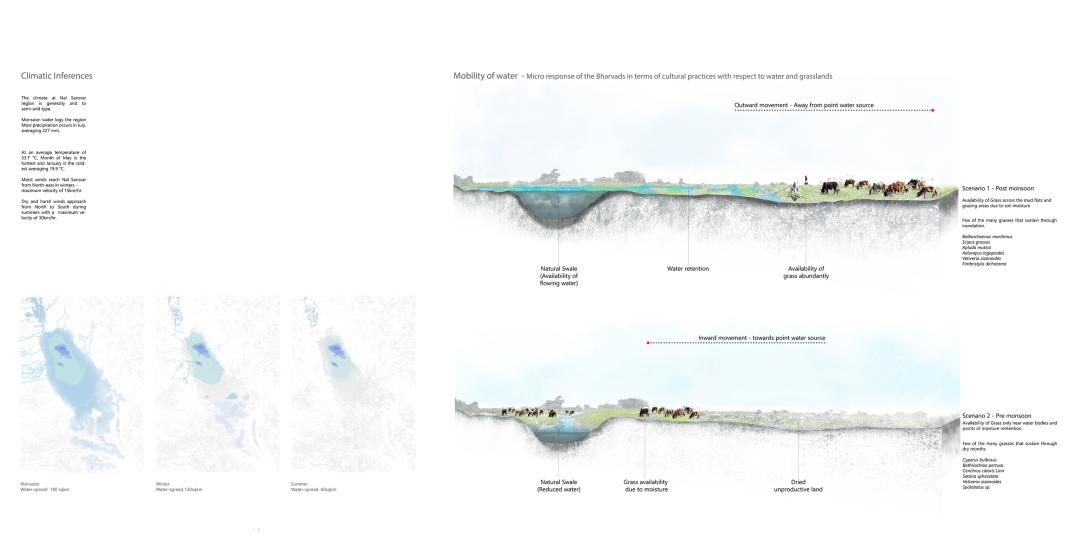

Water has crafted the landscapes of Nal Sarovar. These landscapes have always supported and shaped livelihoods of people who settled around this land-water binary system. The cultural landscapes of Nal Sarovar connect the dots of diverse narratives and legends that brought communities towards this wetland system and established a strong connection with water. This present pastoral land is nothing but the outcome of migrations and the willingness of communities who travelled in search of water and a stable medium for survival: Nal Sarovar formed a perfect combination of land and water for generations to flourish. There are three communities which have migrated to this wetland: Padhars, the primitive tribes, Bharvads, the pastorals, who believe in the legendary hero Lord Krishna to be their ancestor, considering themselves to have followed him to reach Nal-Sarovar, and Sindhi Muslims, who came to develop trade with central India. The proximity of Lothal, the first port city of the Indus Valley Civilization and the trails of connectivity from Dholavira to Nal Sarovar strongly stand as testimonies to the fact that Nal Sarovar was a hot spot for cross-cultural interaction. As river Brahmini, a tributary of Indus, connects these locations together making it evident that all the communities must have followed this trail resulting in a system of migration. While once upon a time they settled along the static waters of Nal Sarovar today they associate multiple interdependencies with the many waters. These interdependencies have now evolved into a set of cultural identities for each clan. For example Bharvads, are shepherds and move in search of grass. The availability of grass, which is in return based on soil moisture, imparts the Bharvads with a landscape ritual of moving away and towards water i.e. being mobile with the appearance and disappearance of grass in respective seasons, covering a loop throughout the year which has been followed for decades.

Dynamics of water - Understanding shift in cultures and rituals

The migration history of communities puts forth the factor of displacement due to survival necessities. The Padhars are greatly dependent on water for fishing activities and earth work, The Bharvads on grasslands and Sindhi Muslims on the agriculture and associated labour opportunities. All the three directly or indirectly have associations with water which generate the economic activity they rely on for their survival. This could be the apparent reason for the antecedent generations to consider water as a nurturing element. Thus they respected and wisely used it while also conserving it for generations to come. But with changing times, globalization, exposure to media, and to the outside world, current generations have a new set of aspirations which are not the continuation of their present way of life. As cultural anthropologists rightly say, the nature of landscape is deeply engrained in the way of its existence, norms, beliefs, art, and expressions of the people who dwell on it. Their aspirations, likewise, are extensions of these collective desires. Present day aspirations, even though devoid of direct associations with the resource, show a faint proof of the rootedness of communities and its cultural links to their surrounding. On the contrary these aspirations somehow direct the locals to move away from this cultural landscape in order to have a better living condition. Unaware of the corresponding consequences, the act of mobility is still prevailing on this land and if it continuous to reoccur at greater frequencies what will be the future of this cultural landscape?

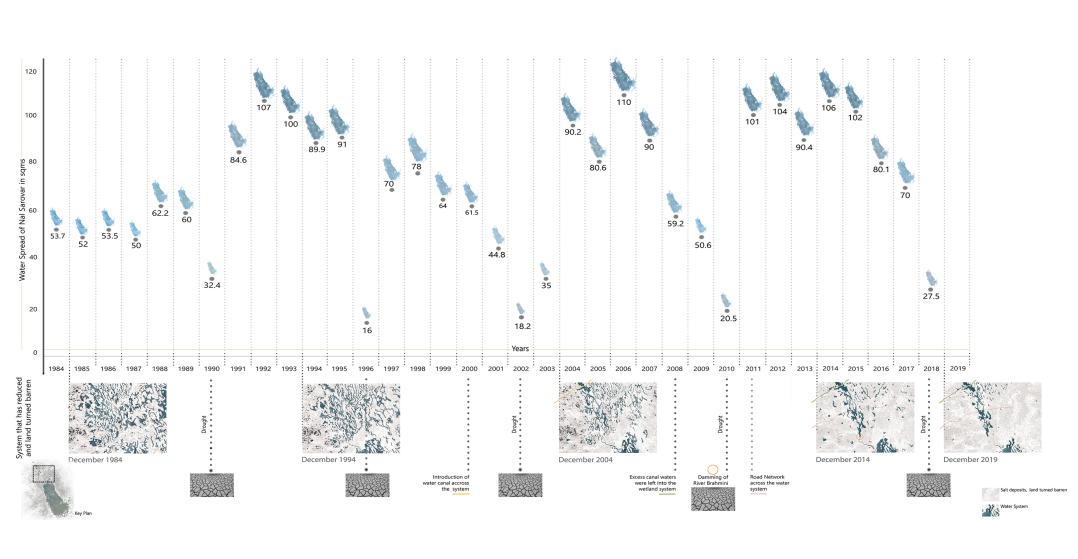

Furthermore, a canal network proposed by the government for the provision of potable water passes in proximity of the Ramsar site. Since 2008, excess water from this canal is leaked into the wetland, changing its ecology from a saline wetland to a deep fresh water lake. The fragmented inflow of river Brahmini is dammed for agricultural purposes, altering the hydrology of the region. In addition, the climate crisis has hampered the inherent flood and drought patterns causing extreme soil denudation and habitat loss. More rain in a short span and prolonged droughts have triggered the systems, increasing the salinity levels in soil, converting fertile land parcels into barrens. Alarmingly, the fragmented river systems have drastically reduced in a short span.

The changing climatic conditions and ignorance towards ancient wisdom have left the current generation living on this pastoral land in a state of hopelessness. They prefer being urban poor and urban homeless rather than rethinking their pastoral land as a productive entity. In the long run, the availability of water as a resource is taken for granted and its importance has been overshadowed by modern aspirations. If turned around and worked wisely with a foresight, these communities can effectively alter their livelihoods without falling prey to the aspirations that deprive them from their own roots.

For instance, Bharvads are the only pastorals who move in search of greener pastures within the landscape. The above factors have drastically consumed the natural grasslands which were traditionally employed as grazing belts enabling the community to raise cows, an important cultural element for pastorals and agrarians alike. The loss of grasslands forced the pastorals to purchase fodder, an uneconomic and unhealthy option for free-grazing cows which have grass palate sensitivity. The Bharvads were forced to shift from rearing cows to domesticating buffalos for better milk yield and economic advantages, leading to loss of indigenous breeds of cows.

Persisting Dynamics - A Tale of Displacement

The earlier stages thus culminate to the fact that water has been a prime source for the region of Bhal to flourish, which is now rapidly losing its prominence, both ecologically and culturally. The fading waters have currently pushed the communities along this wetland into a state of hopelessness resulting in their displacement from the region. If the nature of water is made persistent for longer durations it can bring back the past interrelations and nurture communities for generations, making it possible to reconnect the people with their place and practices, creating a future for this cultural landscape.

Secondly, the land of Nal Kantha has always been saline in nature since it was a part of the sea in history and even today River Brahmini flows down from the great Rann of Kutch, which is a vast salt marsh. The communities in the past followed indigenous practices of treating this land and cows as an important component of this treatment because their manure was used in treating extensive salinity. As such, cows were a part of many cyclic associations, helping in the upkeep of the landscape and thus the survival of the communities. The indigenous year-round practice of treating the land with manure helped maintain the balance of soil salinity and the interlinked water table, leading to fertile land parcels employable in agriculture and grassland cultivation; each component played its definite role in maintaining a symbiotic relationship. The lost breeds of cows are another factor for the current state of this landscape.

Conclusion

The climate crisis has hampered the component “water”, disturbing the entire chain of dependencies and leading to a present day state of despair displacing communities and their practices. Lost waters converted fertile lands into barren, unproductive lands. Lost grasslands made it difficult for pastorals to raise cows and the loss of cows, in return, closed the method of treating the saline land parcels resulting into the loss of ground water table and reduced surface water systems.

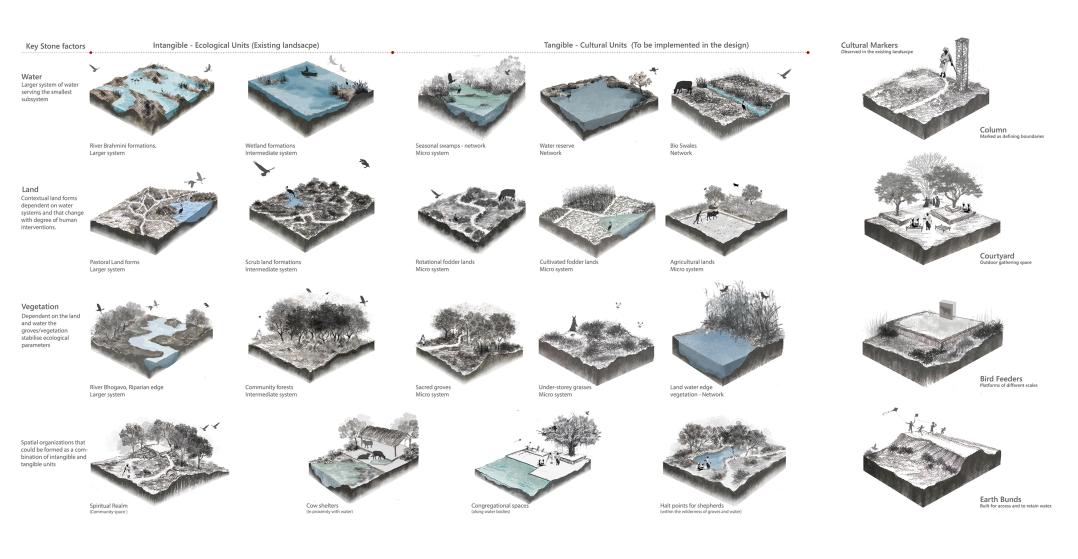

Attempts could be possible in-order to bring back the lost riparian edge along the fragmented river with specific vegetation that fixes soil salinity. This riparian edge can form an identity to the place and could be considered as sacred groves (Orans) which were once a part of this wetland. Once the soil salinity is altered this could bring back the fading water table and positively cater to the cultivation of grasslands helping the pastorals to rear cows. As such, several components of this dynamic landscape could be inserted back for a smooth functioning and future security of the cultural landscape. These interconnections could be tangible as well as intangible in nature and linking them back to this depleting wetland could cater to resolving current issues to a considerably higher degree.

A subtle intervention could act as a catalyst in upgrading livelihoods of the Bharvads, bringing back their cultural association and practices through which indigenous breeds of cows will regain their importance as a cultural element. The cultivated lands will enable the communities to harvest grass year-round and store it for monsoons. The acquired byproducts from manure could be used for fuel related purposes adding to a source of income. It will develop ties between place and pastorals creating an acknowledgment towards the sub-systems and sources of water, which in the present day is fading drastically. Thus keeping them rooted with their inherent practices and securing futures of generation’s while keeping the processes of the cultural landscape alive. Almost infinite and cyclic this process will connect the Bharvads with other communities due to occupational opportunities, like building and maintaining earth bunds by the Padhars, Agricultural labor by Sindhi Muslims, and fodder/manure exchanges, enhancing inter-community dependencies. Methods like establishing sacred groves along the fragmented river system could bring back the lost riparian corridor supporting existing flora fauna, enhancing their habitats to greater degree. Inserts of the grasslands and rotational fodder farms will keep the soil intact controlling over grazing and preventing the resulting soil denudation. The generated correlation between the pastorals and their grasslands will proceed towards a larger collective good, towards a greater sense of belongingness and benefit multiple communities and their inter-dependencies within Nal Sarovar.

The preceding study is on my outcome project from the academic studio “LA 4007 - Tracing Lines - ” conducted for the second semester, at Masters of Landscape Architecture, CEPT University. My sincere thanks to the studio tutor Prof Divya Priyesh Shah for guiding me though out the process and my fellow colleagues who contributed to the collaborative learning process within the studio premises.

Sources:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282757585_Anthropogenic_Pressures_of_Nal_Sarovar_Bird_Sanctuary_Gujarat_India http://saconenvis.nic.in/publication/nal_sarovar.pdf https://vedas.sac.gov.in/vedas/downloads/ertd/Hydrology/L_8_Ramsar_Wetlands_Science_and_Experience_of_Nalsarovar_Dr_T_V_R_Murthy.pdf https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/for-dairy-farmers-preference-moos-from-cow-to-buffalo-117051700815_1.html http://agritech.tnau.ac.in/animal_husbandry/animhus_buffalo%20milking.html http://www.fiapo.org/fiaporg/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/GUIDELINES-FOR-MANAGEMENT-OF-GAUSHALAS.pdf https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/columns/harish-damodaran/cow-belt-or-buffalo-nation/article22985221.ece#

Literature Case Studies:

Quzhon Luming Park by Turenscape Atlanta belt line by Perkins and Will

Key Readings:

This Fissured Land - An Ecological History on India, Madhav Gadgil and Ramchandra Guha Waterscapes, the Cultural Politics of a Natural Resource, Amita Baviskar The Life of Lines - Tim Ingold’s Everybody Loves a Good Drought - P Sainath Soak: Mumbai in an Estuary - Anuradha Mathur, Dilip Da Cunha Grasses and Legumes for Tropical Pastures - B K Trivedi; Indian Grassland and Fodder Research Institute.