Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

Monuments, Public Spaces, and Racial Justice

Injustice Made Material

The production and use of public space are the results of negotiations among different groups of the public. The location, funding, and management of public spaces require participation between different interest groups. Stakeholders are determined by who maintains public space, and who is welcomed or excluded as a user. These conflicts and negotiations are part of a democratic process, as collective decisions are made about how to allocate resources in ostensibly fair and transparent ways. They are also part of how public opinion is formed. People either feel they are true stakeholders in public space (that the spaces belong to them and they have some level of control in the development and management of those places) or that they are excluded. People form these ideas about themselves and about others through using public space. Democratic processes take place through “performative” use and “reinforcing” use of public space. In performative uses, people participate in explicitly political events, such as protests or political gatherings. Over the long term, individuals experience public spaces in ways that solidify either their sense of belonging within or exclusion from the public sphere. This has become especially apparent this year as an ongoing movement towards racial justice has gained attention, and the country has renewed its debate about the significance of public monuments.

PUBLIC SPACES AND THE MOVEMENT TOWARDS RACIAL JUSTICE

This summer, we’ve seen performative uses of public space provide a stark contrast to the months we have spent away from physical public life due to Covid-19. Mass protests in parks, plazas, and streets across the country have given us a physical reminder of what collective action can do. Protests are an easily recognizable and foundational component of democratic systems. The fact that people of all races and from all corners of the country have joined the Black Lives Matter movement in sustained protest has accelerated public recognition of the hostility that Black people experience by police in public space; public opinion is changing. President Trump has also chosen key moments and public sites to create a spectacle that sends clear messages about who is included in the American public. On July 4th, he announced increased law enforcement near national monuments and a 10-year minimum prison sentence for those that deface statues in federally owned public places. [1] The ceremony, the date, and the Blue Angels flyover were performative uses of Mount Rushmore, a public artwork that dominates a landscape that was once property of Cheyenne and Lakota people. Mount Rushmore is a symbol of American power, a symbol meant to intimidate Native Americans, and in this speech it was used to enhance the intimidation of those who protest. Other recent examples of performative use of public space include a Presidential interview directly below the plinth of the Lincoln Memorial (where special events are normally prohibited by Federal Law), and the traditional White House Rose Garden press conferences[2]. These platforms, whose design and history invoke authority, are the sites where messages of division are magnified by the public nature of the spaces. They imply that unequal rights of citizenship are part of our tradition and are a matter of patriotism.

Apart from the key moments when we take notice of the overt symbolism of public space, the ways people use and experience public spaces over time reinforce their sense of belonging. The physical design of public spaces dictates how people move, blocks or allows user access, and facilitates or prevents encounters among individuals and groups. These design elements are as small as furnishings, meant to keep people from lingering, and as big as parks that run along waterfronts or are backed against highways. They send clear messages about who and what is welcome in public space.[3]

Beyond design, public space is where people experience regulation and conflict. The need to conform to social norms can provide clues about who the prevailing authority is. Power relations are produced where people choose whether to follow the rules, and where those rules can be uniformly or selectively enforced. Many of us may have never thought about the reinforcing use of public space; by virtue of being part of the in-group, we always feel welcome. This is not universal. In instances like the Portland protests, violent police and military intervention have been broadcast and documented for our permanent collective memory, but many people experience this kind of hostility in public spaces on a day-to-day basis, undetected by the majority of the population.[4]

PUBLIC SPACES AND MONUMENTS

Another tool of reinforcement is the use of monuments and artistic symbols, which highlight the causes of some eras and groups while leaving out others. Though religion is an important part of public life, each year we see controversies over religious symbols displayed in publicly-owned places (the Ten Commandments at county and state courthouses, a menorah in Cincinnati’s public square, the Wiccan symbol in military cemeteries) because many argue that they give prominence to one faith over others. War memorials often employ heroic language or figurative statues that glorify those who sacrificed. The statue of a soldier and his weapon is a recognizable symbol that tempers the pain of war by glorifying the idealism that led to the American Revolution, the Civil War, the World Wars, and so on. In contrast, consider the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, or the 9/11 Memorial. These examples employ different visual rhetoric, and they also highlight the pain of lives lost in tragic historical events. There are design reviews and public meetings that allow people to weigh in on the decisions about artwork installed in public spaces. However, this was not always the case, and even now, these decisions are mostly made by people who have influence and access to these types of design conversations. Meanwhile, for example, a Confederate monument can paint a supposedly neutral picture about the “brotherly” fight between the North and the South, while conveniently forgetting the experience of people who were enslaved, and thus reinforce the continued less-than-equal belonging of their descendants.[5]

After the White Nationalist protests in Charlottesville in 2017, there was a wave of removals of Confederate monuments.[6] This year, the significance of these monuments is being questioned again, but the debate has expanded to include other historical figures who contributed to the suppression of Black and Indigenous People This has been shocking, as nearly every city and town has a monument to, if not the Confederacy, a European explorer or a founding father who enslaved human beings. There are some who argue that the removal of monuments amounts to wiping away history; by that logic, we are getting rid of almost all of it. This is true if we think of history as being a series of events that took place in the past, obligating us now to glorify the winners and forget the losers. But history is the many stories we tell about what happened in the past, as well as the story we are presently constructing. The choice of keeping these objects in our public spaces reinforces the motives that caused the suppression of Black and Indigenous people, and continually transmits the message that public space is not for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) and by extension, participation in society is also not for them. The sentiment that preserving monuments is about preserving history is misplaced; Instead we should ask what values we want to preserve in the public sphere.

In some places like Birmingham, the Confederate Soldiers & Sailors Monument came down in a typically democratic way. Calls to remove the monument in previous years yielded no results, but after even bigger crowds of protestors rallied around the obelisk less than a week after the death of George Floyd, the mayor sanctioned its removal within days.[7] But sometimes this kind of democratic process doesn’t work. By and large, Black and Indigenous communities are excluded from the decision-making, furthered by decision makers refusal to listen. The message is reinforced, through the symbolism of design and the practice of local government, that participation is not accessible to everyone. That necessitates performative action, and people are finding creative ways to do it.

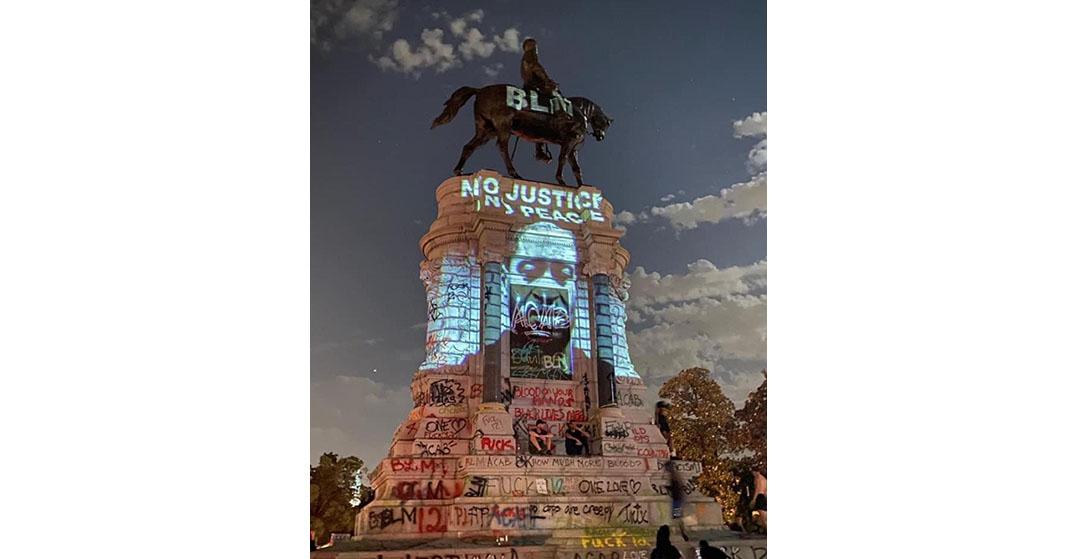

In Richmond, the former capital of the Confederacy, the Robert E. Lee statue still stands. But protestors continue to add layers of spray-painted messages and the names of Black people who have died at the hands of police. It’s become a backdrop for photoshoots and an art installation featuring a portrait of George Floyd.[8] These types of temporary actions demand a changing meaning of public space by bringing Black experience to the foreground. They insist on being recognized as part of the public. Elsewhere in Virginia, a whipping post used to face the square in Old Towne Portsmouth. Until recently, it was the site of four Confederate statues. This is not a subtle reinforcement, and eventually it provoked an equally explicit performative gesture. Protestors beheaded all four statues while a marching band played and demonstrators danced. More than a month later, the Portsmouth City Council finally voted to relocate the bases of the four statues to storage.[9] [10] Here public space served its purpose by being a platform for the public – as unrecognized as some users were, they used these spaces to practice democracy.

The shared history behind both monuments and their public spaces is what gives them their meaning, and the performative tearing down of monuments will also be part of their histories. While public spaces are only one example of the ways the planning and management of cities have excluded Black, Indigenous and people of color, they are a tool to reinforce the messages of exclusion built into other planning systems. Historical monuments are often the central organizing element of public spaces, so their destruction is an appeal to re-structure systems that are also centered on inequitable allocation of resources.

The negative reaction that many people have had to the destruction of public monuments comes from seeing the interruption of a public space that feels representative of them. It is easy to avoid reflecting on this representation when public space is designed in a way that continually reinforces one’s belonging. Meanwhile, others are actively excluded; they do not have the same sentimental reaction to public artwork because they have always known it was not for them. As users of public spaces, and for those of us who design them, it is important to consider how we reinforce our own belonging and that of others. The way we develop and use public space is a way that we collectively define who “the public” is, and how we may participate together in public life.

[1] Michael Crowley, Trump Says He Will Create a Statuary Park Honoring ‘American Heroes’, New York Times, July 4, 2020.

[2] Katie Rogers, “Most Events in the Lincoln Memorial Are Banned. Trump Got an Exception”, The New York Times, May 4, 2020,

[3] John Parkinson, Democracy and Public Space: The Physical Sites of Democratic Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

[4] Sharon Zukin, “Reimagining Civil Society: Conflict and Control in the City's Public Spaces”, Public space: between reimagination and (pp. 17 - 30). 2018. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

[5] Dell Upton, “Confederate Monuments and Civic Values in the Wake of Charlottesville”, Society of Architectural Historians, September 13, 2017.https://www.sah.org/publications-and-research/sah-blog/sah-blog/2017/09/13/confederate-monuments-and-civic-values-in-the-wake-of-charlottesville)

[6] Jess Bidgood, Matthew Block Morrigan, Morrigan Mccarthy, Liam Stack, and Wilson Andrews, “From 2017: Confederate Monuments Are Coming Down Across the United States. Here’s a List”, The New York Times, August 28, 2017.https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/08/16/us/confederate-monuments-removed.html?searchResultPosition=1

[7] Connor Sheets, “Obituary for a racist symbol: Birmingham takes down Confederate monument after 115 years”, Advance Local, June 2, 2020. https://www.al.com/news/2020/06/obituary-for-a-racist-symbol-birmingham-takes-down-confederate-monument-after-115-years.html?fbclid=IwAR3Q56WLgcnQm_WcQOTFwoct2sG_TxPZqUZXSMTn53jvnjxDBbgx_-PsDDU

[8] Sarah Mccammon, “In Richmond, Va., Protesters Transform A Confederate Statue”, National Public Radio, June 12, 2020.https://www.npr.org/2020/06/12/876124924/in-richmond-va-protestors-transform-a-confederate-statue

[9] Ana Ley, Saleen Martin, and Matt Jones, “Portsmouth Confederate statues beheaded, partially pulled down by protesters”, The Virginian Pilot, June 10, 2020. https://www.pilotonline.com/news/vp-nw-portsmouth-confederate-monument-20200610-65p7wr3nkvcrneaotwycjygcqu-story.html

[10] Katherine Hafner, Amir Vera, and Ryan Murphy, “Intentional or not, local Confederate monuments were built on or near former slave sites”, The Virginian Pilot, August 18, 2017. https://www.pilotonline.com/history/article_c09deef2-f83c-5181-837b-23970020b2fc.html