Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

The Great Lakes Architectural Expedition

1<WORLD<2

On December 8th, 2008, the States and Territories of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Montreal, and Quebec, signed into law the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact [The Great Lakes Compact], prohibiting water removal outside the Lakes’ drainage basins and creating a sealed eco-political zone within the United States and Canada.[1] On April 25th 2018, Wisconsin approved Foxconn’s request to withdraw 7 million gallons of Lake Michigan water per day for a private LCD panel factory outside Racine: Foxconn claimed its factory’s water consumption a “public use” to skirt full Compact review. This feat of semantics exposed the Compact’s lack of actionable public water definitions, and created a leak in the Compact’s closed loop.[2]

Finally, on February 26th, 2019, the citizens of Toledo, Ohio approved the Lake Erie Bill of Rights, granting the city legal guardianship of the Lake and its’ watershed. Unchecked agricultural runoff in 2014 had rendered Lake Erie’s water undrinkable for half a million people for days at a time: algal blooms would return regardless in July 2019.[3]

The question of architecture’s role in defining publics or constituencies in a time of climate crisis, especially when those publics and constituencies are governed by overlapping or conflicting jurisdictions, drives the representational strategies at work in The Great Lakes Architectural Expedition. Using the work of the titular—fictional—public architecture office as a lens, the show explores how the practice of architecture might shift in the near future; away from singular, private clients and discrete buildings, and towards managing complex systems of infrastructure, maintenance, and advocacy on behalf of collective, public entities. The Expedition’s projects are as much arguments for how things ought to be as proposals for specific structures, re-calibrating the expectation of objectivity within architectural representation is critical to this practice. The canonical Expedition projects on display in the gallery de-center architectural perspective by shifting scale to highlight specific concepts, leveraging color as a data and coding system, and engaging with “impossible” perspectives through 3D modeling software to state their case.

The Expedition

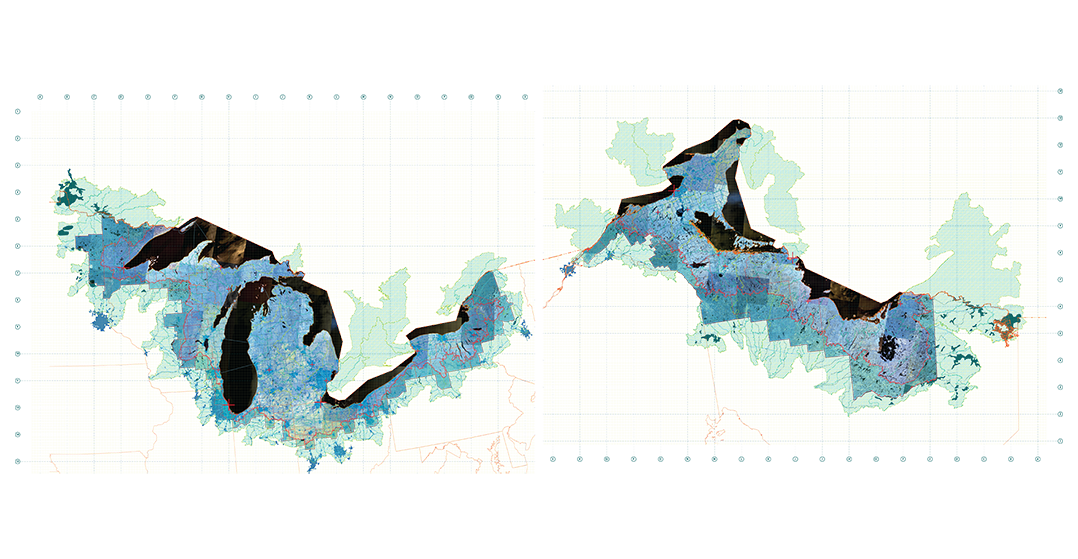

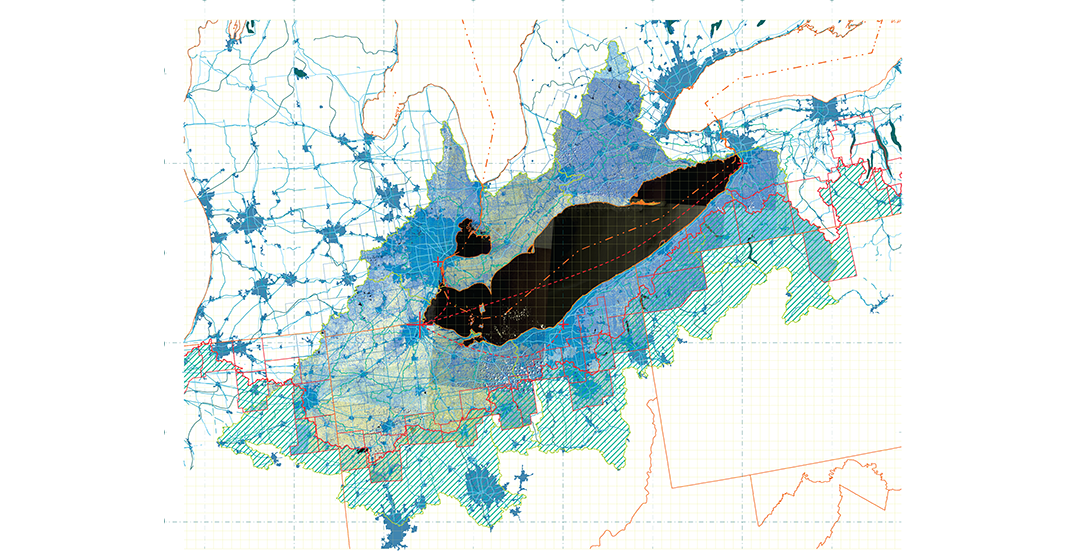

Acts of representational manipulation begin with the cartography of the Great Lakes Compact itself. The map on display in the Great Lakes Architectural Expedition splits the basin along the Canadian-USA border, representing the Compact’s limits as they truly are: a new border between distinct publics. Because the new borderland dividing the Great Lakes Compact zone from the rest of the United States and Canada is largely invisible - a change in drainage slope almost imperceptible to the naked eye - cartographic tools render the new dividing lines knowable, understandable, and open to engagement.

All maps use LANDSAT satellite false-color composites for underlays, which translate infrared data into Red, Green, and Blue. In these composites, blue areas show vegetation, yellow urban areas, and water in black. The new boundaries of the Great Lakes Architectural Expedition are slippery; a thin line demarcated by the topography of watershed basins, expanded and complicated by bridging counties, cities, and states. Maps are therefore used here not as markers of precise locations, but rather as signposts for emergent re-agglomerations of public interests along hydrological dimensions, and the slippage that occurs across these boundary zones.

The Last Impervious Surface in Portage County Ohio

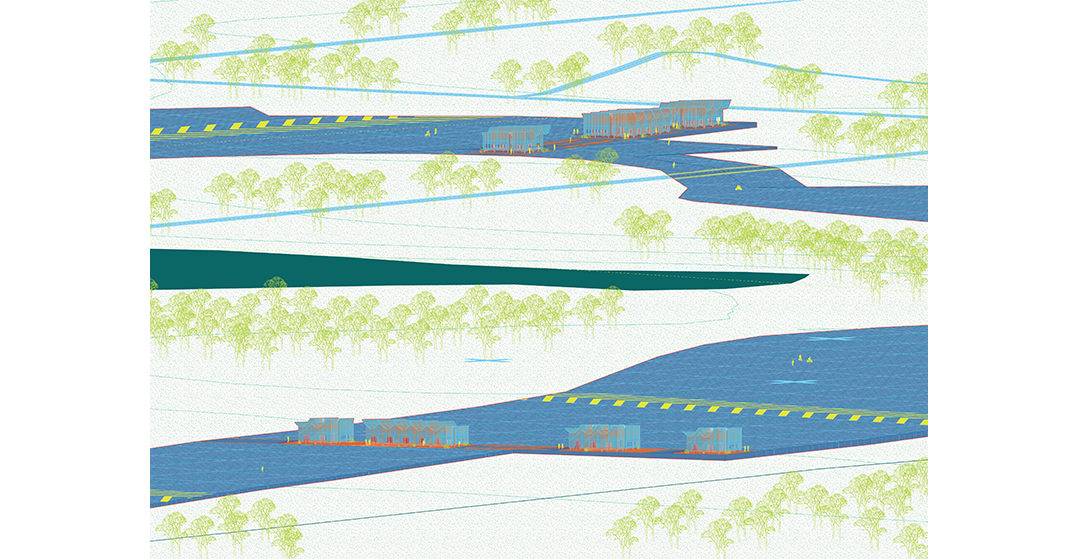

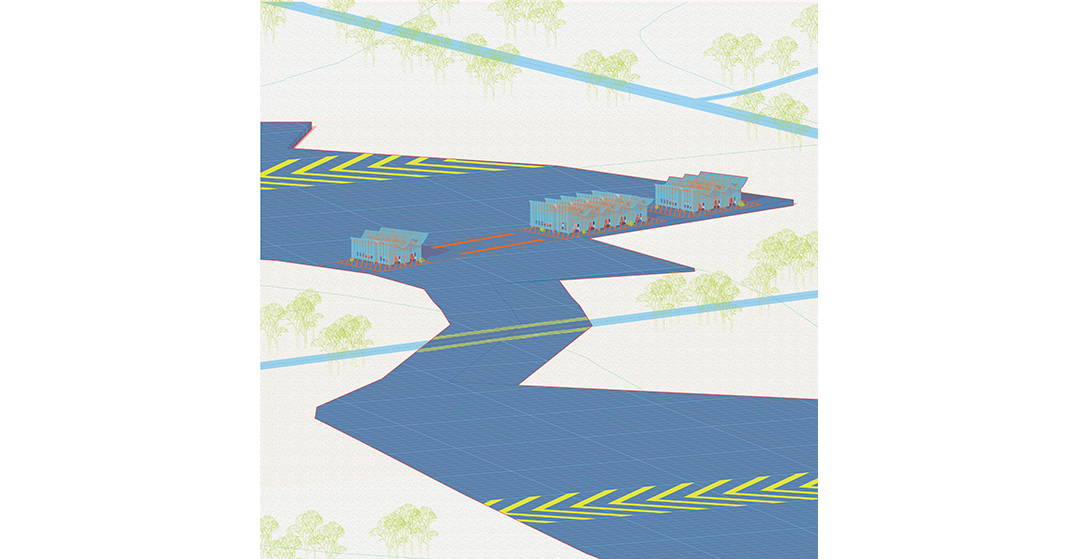

The Last Impervious Surface in Portage County, Ohio examines precisely this disjuncture using the (fictional) Portage County Spillway - a 30-mile long, 500-foot wide, 5-foot tall asphalt megastructure spanning Portage County - as a lens. The Spillway is able to redirect enough rainfall away from the Ohio River basin towards neighboring Akron to support 100,000 people per year: the megastructure was rehabilitated by the Great Lakes Architectural Expedition to create a continuous public space for the entire county. Simultaneously, the Expedition introduced a ban on the construction of further impervious surfaces county-wide to ensure no further alterations to the county’s topography. The Portage County spillway is a natural foil to the present-day schism between political boundaries and the material necessities of preserving access to the Great Lakes’ water; a gap the Compact has thus far tried to bridge with mixed results. In an era of increasing scarcity, material stewardship is increasingly important. Implicit in this conception is an understanding of where regimes of material ownership and regulation do, and do not, align.

A 1’ = 500’ model of a portion of the Portage County Spillway divides the gallery. The vertical axis is exaggerated by a factor of 30 in order to highlight the critical changes in topography dividing the Lake Erie and Ohio River watersheds. These scale changes act as magnifiers, bringing architectural-scale details and the minuscule slope of a watershed basin into focus while preserving the planimetric relationships between the Spillway and its context. Similarly, isometric drawings accompanying the Spillway models use parallel perspective to force foreground and background objects into the same viewing plane, retaining relative size and allowing a sort of artificial panorama to occur; almost an elevation-perspective.

The Maumee Basin Phosphorus Co-op

The Maumee Basin Phosphorus Co-op is a collective agricultural infrastructure network undertaken by the Great Lakes Architectural Expedition, in collaboration with Lake Erie’s representatives and a coalition of farmers in the Maumee River watershed basin outside Toledo, Ohio. Clusters of algal turf scrubbers pass agricultural runoff over an acre of algae-covered mesh curtains, removing toxins and sequestering carbon simultaneously. Collected around the tributaries of the Maumee River, the scrubbers join the agricultural-industrial landscape of northwest Ohio, preventing harmful algal blooms in Lake Erie. Infrastructure at the scale of industrial concerns represents the only viable response to structural threats to Lake Erie’s watersheds. However, we must be careful to position these infrastructure updates and innovations to serve not only private interests but collective needs as well.

The centerpiece of the Co-op in Banvard Gallery is a 1:500,000 meter relief model of the entire Maumee Watershed basin stretching from Toledo, Ohio to Fort Wayne, Indiana. Using government data to assign phosphorus loading values on each sub-watershed, these values were interpolated into a height field, shifting purely cartographic data into a measurement of the health of the entire drainage basin. Once again, model making generates an artifact that is both document and diagrammatic, positioning the architects of the Expedition as advocates for their client, Lake Erie.

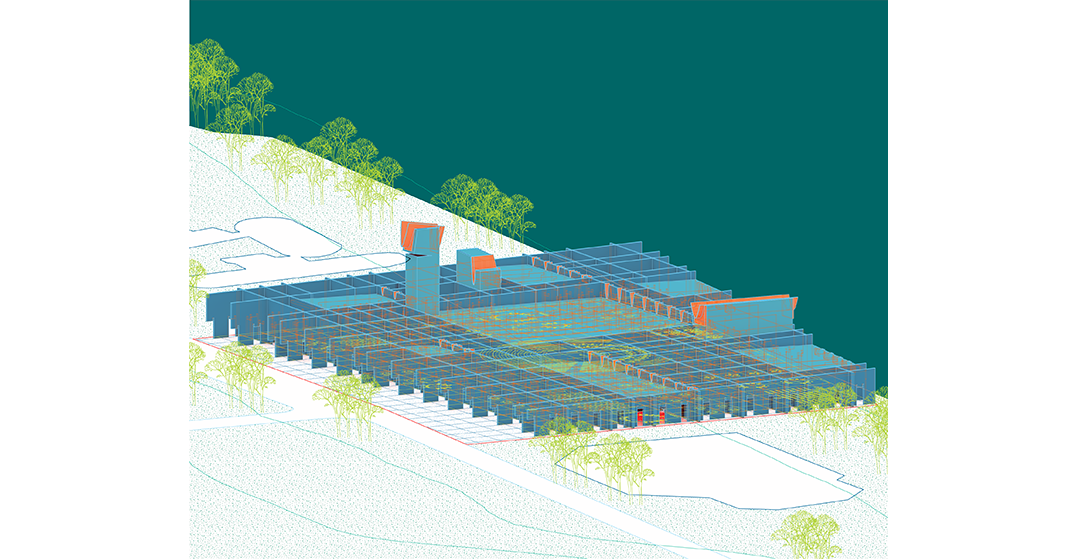

The Parliament for a Material World

The Parliament for a Material World is housed at the Toledo headquarters of the Great Lakes Architectural Expedition. A new model for the expanded role of architectural practice in the Lake Erie watershed, the Expedition’s facilities house classrooms, public squares, design offices, conference rooms, and the Parliament chamber. The Parliament itself facilitates the representation of Lake Erie in all building proposals within the watershed; a representative from each of the Lake’s watersheds is elected to advocate for the watershed’s public materials and resources. These representatives negotiate with the Expedition’s clients for public concessions and can initiate Expedition projects at their request. Architects are not substitutes for governors or elected politicians: however, architects most certainly can do more to increase their engagement with critical issues of social and environmental equity. Simply offering design services is not enough – expanding architectural practice to encompass education, public information campaigns, and pursuing robust public works is a pathway to putting architectural expertise to work addressing the climate crisis.

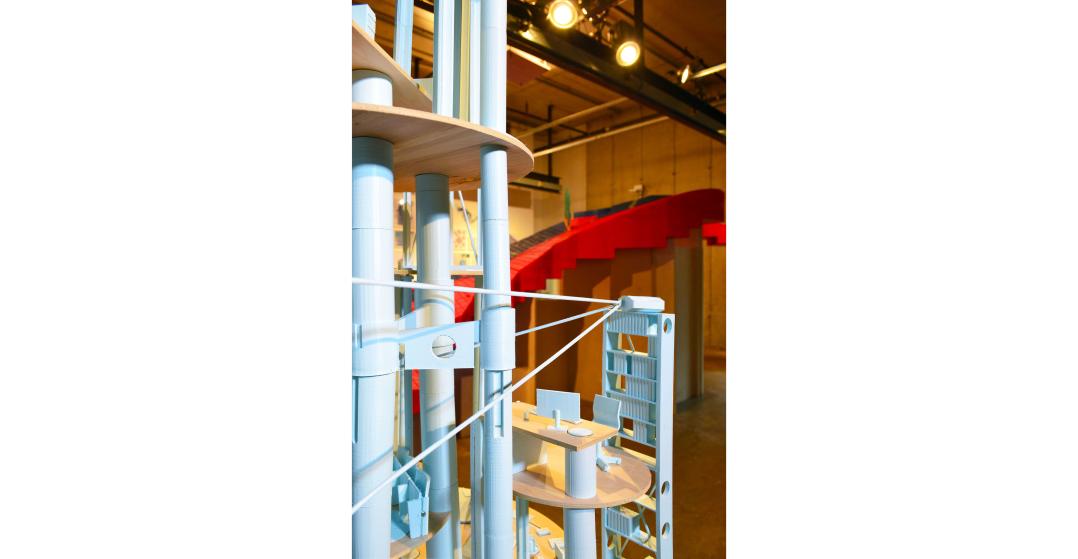

A 1” = 1’-0” detail collage model of all the furniture where the Parliament transacts its business accompanies an “architectural”, un-distorted, 1/4” = 1’-0” model of the Expedition’s headquarters on the banks of the Maumee River. Stripping away ornament and enclosure, the furniture model focuses on the workstations, conference tables, and deliberation chambers where the future of the Lake Erie watershed is decided.

Conclusion

While the Great Lakes Architectural Expedition remains a fiction –for now– the foundational questions of material stewardship, public access to communal resources, and future role of architects remain. Meanwhile, events on the ground continue to trend in negative directions: relentless wildfires in Australia, California, and Siberia, global stress on fresh water supplies, and the over-extraction of key resources like sand and rare earth minerals. The Great Lakes region will not be immune to the changes and challenges of climate catastrophe and over-leveraging of natural resources: the fact remains that the “public” Foxconn factory is being constructed outside of Racine, and the Lake Erie Bill of Rights was struck down in court a year after Toledo citizens voted it into law. Forward progress on environmental issues is no guarantee. In order for architects to address the profound challenges ahead, we must re-evaluate our tools and techniques. The Great Lakes Architectural Expedition argues a change in representation is afoot, shifting from documentation to argumention, and signaling the possibilities of architects as advocates, engaged citizens, and agents of environmental equity.

Project Credits:

Curator / Designer: Galen Pardee

Fabrication and Installation Assistants: Anthony Selvaggio, Melissa Folzenlogen, Noël Michel, Patrick Sardo, Kate Lubbers, Sofia Kuspan

Sponsors: The Howard E. LeFevre Emerging Practitioner Fellowship, The Ohio State University Knowlton School of Architecture.

Public Water Studio, Spring 2020: Matt Capitelli, Noah Ferriman, David Johnson, Sofia Kuspan, Kate Lubbers, Andrew Puppos, Patrick Sardo, Nate Sullivan.

**Join Galen Pardee for a virtual lecture on October 14th. The lecture can be seen HERE**

[1] “Great Lakes—St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resource Compact,” 110th Congress, accessed September 29, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/110/plaws/publ342/PLAW-110publ342.pdf

[2] Corrinne Hess, “Approval for Foxconn Great Lakes Water Diversion Upheld,” Wisconsin Public Radio, June 11, 2019, https://www.wpr.org/approval-foxconn-great-lakes-water-diversion-upheld

[3] Daniel McGraw, “Ohio City Votes to Give Lake Erie Personhood Status Over Algae Blooms,” The Guardian, February 28, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/feb/28/toledo-lake-erie-personhood-status-bill-of-rights-algae-bloom#:~:text=But%20this%20week%2C%20more%20than,human%20being%20or%20corporation%20would