Join our mailing list and receive invitations to our events and updates on our research in your inbox.

Cultural Stimuli in the Himalayan Landscapes

1<WORLD<2

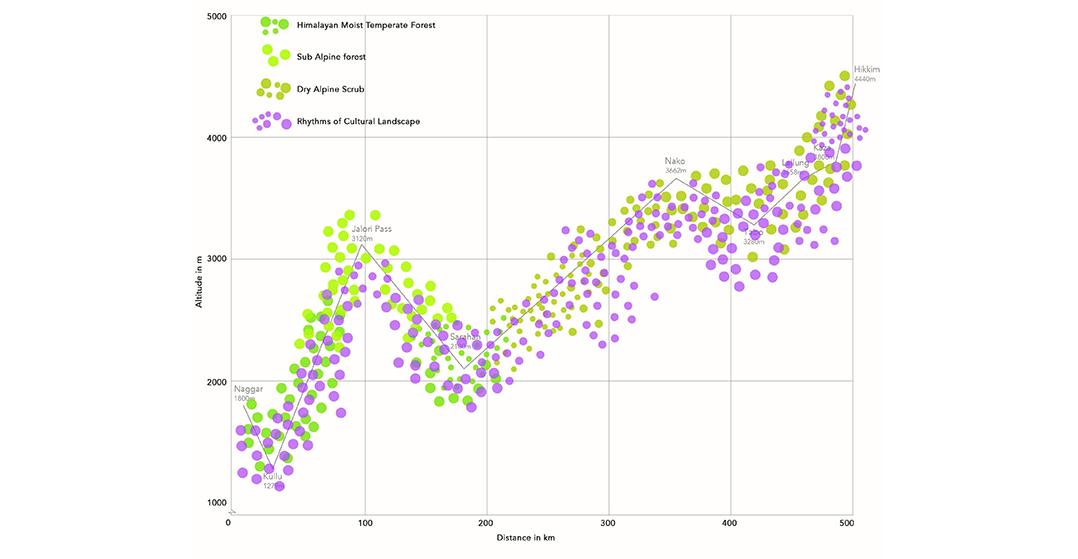

Landscapes are the underpinnings to any form of life. Experimentations in the field have long been resolving ways for human needs and practices, impacting the biodiversity through changing inter-dependencies. Traversing in a Himalayan region proffers deep understanding of the relation between landscapes and its impact on life forms. Following are the notes and narratives from a journey undertaken in the summer of May 2019 from the Lesser Himalayas, towards Greater Himalayas, and transcending the Trans-Himalayas. A spectacular transition can be observed from the forest landscapes (Shimla Hills) to the barren landscapes (Spiti Valley). It is further revealed how altitude variation exacts upon to lead a cold mountain desert from a lush green jungle. The weaving of culture into landscapes is extremely profound. I observed that while faith becomes a pioneer steward of the local landscapes, human practices offer a controlled and sensitive stewardship through their interwoven cultural and traditional practices.

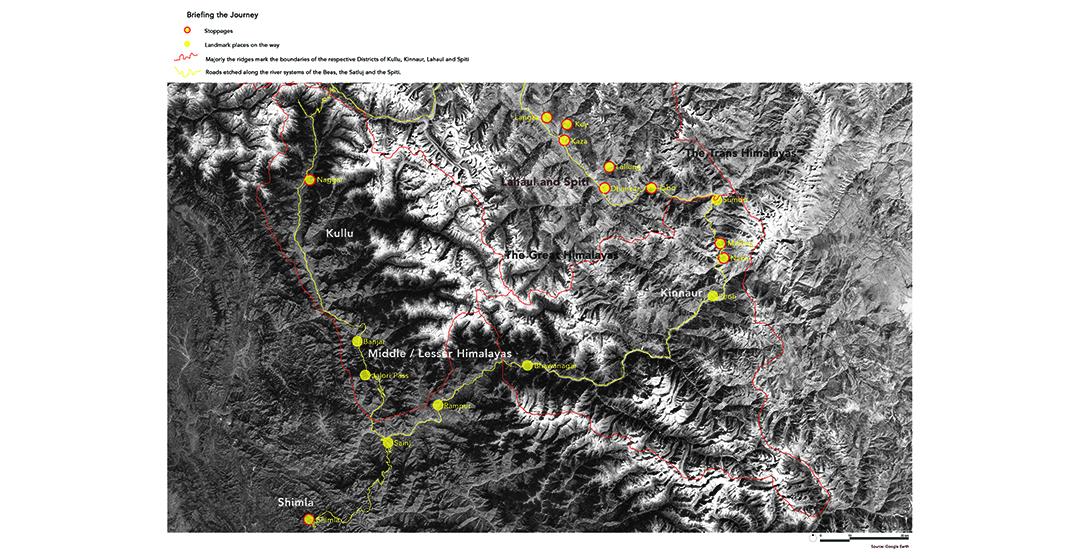

Journey at a Glimpse

Shimla, the capital of Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh, comprises of forests ranging from Himalayan Moist Temperate type to Sub-Alpine type. As one proceeds towards Kinnaur and Spiti valley the forest type translates into a dry alpine scrub, eventually leading to a cold desert. Such variations employ the possibilities of numerous species to thrive in the ecosystems, and find their niches, including humans. Spiti valley constitutes harsh barrenness as its location falls on the leeward side of Himalayas leaving it cold and further low on precipitation. Hence, it is often labelled as a ‘cold desert biome’. Such transitions in the landscape amount to challenging lifestyles for people who have honed their cultures to attain a harmonious living with nature. Therefore, cultural landscapes are elemental bodies which have proven to assist people, their livelihood, and ecosystems in which they live. After all, according to UNESCO [1] (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), cultural landscapes are the representative of the combined works of nature and humankind. They express a long and intimate relationship between people and their natural environment.

Himalayan Landscapes and Materials

Traditionally, in the lesser Himalayan region, fundamental materials of construction have been wood and stone. Kath-kuni architecture[2] has prevailed in the region leading to thermally responsive and earthquake resistant buildings. However, with the coming of new materials, old structures are increasingly considered insignificant. Recently, in the village of Jana (Kullu), an old temple was demolished. People said, “aur shobhla banayenge! (Will construct a more beautiful one!)”. The need for the local architectural practices of ‘Kath-kuni’ or ‘Dhajji-dewari’ [3] to be restored and re-incorporated would take the pressure off the system and promote coherence in human habitats with their immediate contexts. [4]

Moving towards the Trans-Himalayan region, local construction practices are still guided by materials such as mud, stone, and wood. In Kinnaur and Spiti valley, building homes with mud walls and flat roofs is prevalent which protect its inhabitants thermally. Meanwhile, people have swayed away into the lure of ‘pucca houses’ made from brick and concrete. This myth was busted soon with the onset of winter. People went back to their old mud houses for their thermal effectiveness in resisting the harsh climate. People are getting sensitized to bring this back as a mainstream practice so that traditional methods of construction are valued; homes and monasteries continue to nestle harmoniously with the landscape.

Before the advent of modern practices, people have long developed skills and ways of living which let them delve with nature. Facing tough challenges in life and working hard to overcome the same must have been sewn into their DNA. Surely, tough landscapes have made people from the valley rough and strong. Landscapes are clearly responsible in shaping the attitudes of people. This is the power of harsh landscapes in the Himalayan region.

Nako’s Narrative (Towards the Great Himalayas)

Enshrouded by the Willows, Poplars, and farming lands, a body of water rests on the slopes of brown barren mountains. Nako Lake is the nucleus of Nako village that lies on the slopes of Mt. Reo Purgyil. In times where climate change and planetary warming are the most inevitable phenomena, Nako Lake is acting as an ecosystem that supports various flocks of birds and schools of fish. However, what makes this lake still function ecologically is not any Governmental regulation or a policy but the religious sentiments of the local people. Nako Lake is an embodiment of piousness. It is believed that Lord Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche, an incarnation of Lord Buddha) meditated near the lake and thus is sacred in the eyes of people. The sanctity of Nako Lake has gravity towards multi-dimensional significances. Reverence prevents any litter from the tourists and doesn’t allow bathing or even fishing. In return, the lake remains crystal clean and functions as a continuum of interdependent ecosystems.

Tourism has seen a dramatic spike in the last decade. It can be seen as a recent blink in the eye of an ancient multiverse which has caused alarming implications for the health of Himalayan landscapes. Tourism has aided the livelihood of villagers but insensitivity towards such remote landscapes has led to grave disturbances in the system.

A pathway has been built around the lake to walk or perform circumambulation. Many similar waterbodies or sources of water are facing immense challenges in the Himalayan state as more and more infrastructural projects are incessantly being built. In such a scenario, a religious spine assisting ecosystems to thrive is a matter of relief and responsibility, bringing into light the role of culture in protecting biodiversity.

Notes from Malling (The Great Himalayas)

Malling, weaver’s village, is located near Nako. It is known for its traditional Kinnauri weaving on pit looms. The designs resonate with certain symbols and vivid colours. Weaving is a painstaking process which is traditionally driven by community participation as people weave for special ceremonies or communal occasions. The woven pieces can be draped leading to a feeling of warmth, preparing people to bundle up against the possibility of cold. These practices are getting diluted as landscapes continue to become vulnerable to the outside world and may not be successfully transferred to the coming generations.

Local crafts and practices are always a key to deepen the relation between people and landscapes. People are proud of their place and the landscape to which they belong. I found them protective of their villages and ready to fight for the greater good. Recent times of COVID-19 have led to people from the valley protesting the entry of any outsider. Women in Spiti have created headlines, leading the front to protect their villages from any possibility of the virus’s spread. T. Such strong moves are sown deep inside people’s hearts and beliefs which are characterised by the landscapes they have lived in for centuries.

Symbolism – The Great Himalayas to the Trans-Himalayas

Buddhism has painted the barren landscapes of Kinnaur and Spiti valley like a rainbow to a storm. Vivid flags, carved stones, prayer wheels, and Thangka paintings are an integral part of the landscape, forming an identity for the people within them. This reflects the beauty of a culture that bows to the mountains and celebrates life.

Mane stones are the stones or rocks on which are inscribed Buddhist mantras. They are placed on the banks of roads, marking thresholds of the villages in the form of long walls or cairns. Acting as cultural markers, these stones are important identity makers for the landscape. Further, certain architectural features are inspired from cultural beliefs such as painting the perimeters of windows with black color because it is believed that it wards off any evil from the homes just like the function of kohl in the eyes. This imparts a unique character to the architectural reading of a place. Colourful buntings reverberate the essence of mantras through wind, transforming the entire landscape into a manifestation of spiritual presence. Therefore, cultural practices or religious beliefs are a reinforcement in the laps of giant crouching mountains that are bare and brown. This cultivates importance of a delicate human-nature relationship.

Cultural Landscapes – Spiti Valley (The Trans-Himalayas)

The Himalayan belt is known for various stone fruits (peaches, plums, apricots, almonds and cherries) as well as pome fruits (apples and pears). The orchards are prevalent in the regions of Kullu, Shimla, till Spiti Valley.

Farming of peas, pulses and potatoes echoes in the valley dictating mountainous landscapes through step farming. Stone bunds help in holding the soil as well as moisture for the crops. In the past 20-25 years, Spiti, in particular, has come to have a simulacrum of the apple orchards and has developed a system in its lower regions such as Tabo.

Epilogue

People have been in a long relationship with landscapes since antiquity owing to increasing dependencies with civilization. Spiti valley holds one of the most rugged terrains, increasing the hardships of people living in this landscape. The valley holds centuries old monasteries envisioned by an ancient West-Tibetan king. The faith held by people is represented by landscape elements such as water bodies, stones, rocks, or mountains. The apple orchards in the regions of Shimla, Kinnaur and Kullu have long been existing since the British colonial times while Spiti is relatively a recent entrant. This is a result of people’s participation in laying the economic parameters of the area due to newer reforms that have come into the picture in the last 50 years. For instance, saplings of apple trees are being brought in the Spiti valley from America to test run their performance and for research purpose in this climate. Farming is a predominant occupation in the state. So, landforms are garlanded by bunds from step to step, many times till the bottom of the valleys. Such practices give an image to the landscape and opens up its window to the outside world. Culture is a value-addition to the landscape. For instance, the brown barren valleys in Spiti are represented by Buddhism, in the form of symbols, Chortens, Stupas or Buntings with their bright colours adding more life to the sight and adding vivid contrasts. The highest spaces in these regions are conventionally endowed with the religious landmarks.

Landscapes have held a capricious impression in the earlier times, the dissolution of which graduated as people progressed in tapping the natural resources. Still, Spiti Valley is remarkably successful in reminding us and making us realise our mere existence in a larger context. It becomes a grave responsibility to understand the landscapes and our nature of intervening into its receptacles. While strong landscapes determine the attitudes of the people dwelling under it, people equally hold the onus of responding sensitively. This sensitisation on a longer run will sow deep promises of man with nature and reap a successful ecosystem.

Thou! Like the Great Grandfather,

Strange and Strong.

Proud, in the way Thou stand,

By a river, narrow but long.

Stubborn in Thy dominance,

Thou crouch on, to guard.

Rocks, trees, in reverence,

Turn bare and hard.

Thy strict facial expression,

Hones the attitudes of lives.

Thy high altitudes,

Infuse coldness in mind.

Thence mind relentlessly longs

Solitude in Thine old arms.

In a trance, I leave the thoughts

Of anything I can jot.

Before Thy cold desert,

Dear Spiti,

My being is only a dot,

My being is only a dot.

[1] W. UNESCO, "Cultural Landscapes," [Online]. Available: https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/. [Accessed 2019 05 30]

[2]Abhyankar, "Architectural Digest," 27 05 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.architecturaldigest.in/content/himachal-pradesh-traditional….

[3]T. W. C. I. J. d.-S. R. L. K. M. O. Hicyilmaz, "Seismic Performance of Dhajji Dewari," 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.iitk.ac.in/nicee/wcee/article/WCEE2012_2691.pdf.

[4]S. Banerjee, "In Himalayas, quake-resistant tradition losing to ‘modernity ..," The Times Of India, 21 07 2019. [Online]. Available: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chandigarh/in-himalayas-quake-….